Denmark Strait cataract: The world's largest waterfall, hidden underwater and unlike any other on land

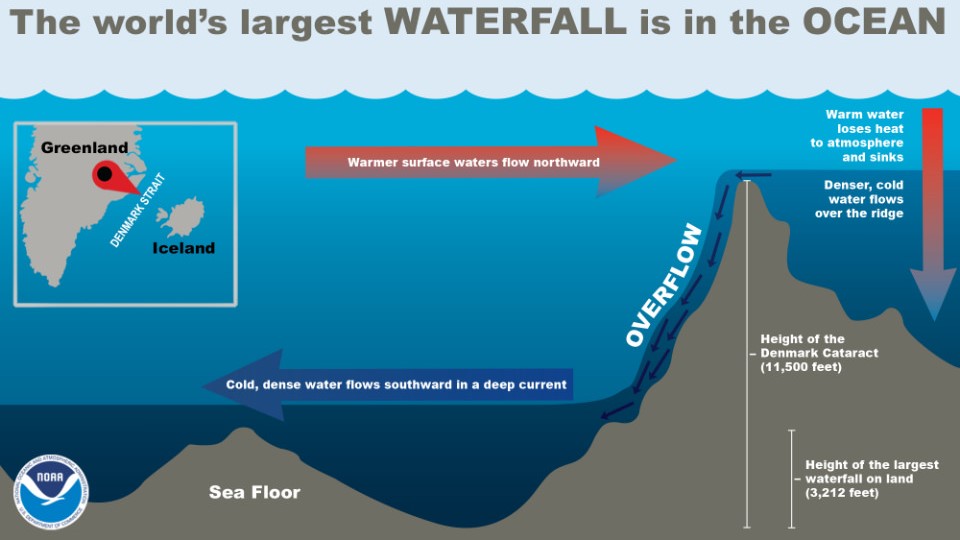

The Denmark Strait cataract is a sloping portion of the seafloor between Iceland and Greenland that funnels cold water from the Nordic Seas into the Irminger Sea, fueling Atlantic Ocean currents.

Name: Denmark Strait cataract

Location: Denmark Strait

Coordinates: 67.06195932031873, -23.96634920730749

Why it's incredible: The cataract is the world's biggest waterfall, taller even than Angel Falls.

The Denmark Strait cataract is a submarine waterfall in the ocean channel between Iceland and Greenland. It is technically the world's largest waterfall, with waters plunging 11,500 feet (3,500 meters) down a slope from the top of the cataract to its bottom.

The waterfall itself is about 6,600 feet (2,000 m) tall, because it lands in a deep pool of cold water that spans the remainder of the slope. That's still double the height of Angel Falls — the tallest waterfall on land — even if the Denmark Strait cataract doesn't look as dramatic as the landmark in Venezuela.

Related: Blood Falls: Antarctica's crimson waterfall forged from an ancient hidden heart

The cataract is as wide as the Denmark Strait, roughly 300 miles (480 kilometers) across, and the seabed drops off over a length of 310 to 370 miles (500 to 600 km). "If we visualize it, it looks like a relatively low-gradient slope," Mike Clare, leader of marine geosystems at the U.K.'s National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, previously told Live Science.

As a result, water gushing down the cataract moves at much slower speeds than those recorded at other waterfalls — 1.6 feet per second (0.5 meters per second) compared with 100 feet per second (30.5 m/s) at Niagara Falls, for example. "If you were down there, you probably wouldn't notice a whole heap going on," Clare said.

Glaciers carved out the Denmark Strait cataract between 17,500 and 11,500 years ago, during the last ice age. The waterfall straddles the Arctic circle and funnels polar waters from the Greenland, Norwegian and Iceland seas into the Irminger Sea, a region of the North Atlantic that is crucial for Atlantic-wide ocean circulation.

The waters north of the cataract are about 1,300 feet (400 m) deep, but only the bottom 660 feet (200 m) cascade down the slope. The top half sits at the surface and mixes with water flowing northward through the strait. After exiting the Denmark Strait, the bottom half continues south along the seabed to the Antarctic, where it enters a global loop of ocean currents called the thermohaline circulation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

None of this is visible above the waves in the Denmark Strait. "At the surface, you have typical sunny Arctic conditions," Anna Sanchez Vidal, a professor of marine science at the University of Barcelona in Spain who led a research expedition to the strait in 2023, previously told Live Science.

The waterfall isn't detectable from space either, she said, except through mapping indicators, such as temperature and salinity.

The Denmark Strait cataract isn't the only known underwater waterfall, although other documented cascades can't compete with it in size. There are features known as knickpoints that often occur along continental margins that look a lot more like waterfalls on land, Clare said, but these are small in comparison to the monstrous cataract.

Discover more incredible places, where we highlight the fantastic history and science behind some of the most dramatic landscapes on Earth.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.