'Dragon' and 'tree of life' hydrothermal vents discovered in Arctic region scientists thought was geologically dead

Researchers have discovered a deep-sea hydrothermal vent field near Svalbard in an area previously assumed to be geologically inactive. The newfound vents have been named after various entities from Norse mythology.

Scientists have discovered a never-before-seen hydrothermal vent system hiding in a highly unlikely spot on the Arctic seafloor. The deep-sea vents, which pump out scalding-hot water and mysterious metals, are located in an area researchers thought was geologically dead.

The newly discovered vents, named after various entities from Norse mythology, lie at a depth of around 9,850 feet (3,000 meters) southwest of Svalbard — a Norwegian archipelago within the Arctic Circle. The field, which is named the Jøtul hydrothermal field after a race of beings from Norse mythology known as the giants, or "jötnar," is around 3,300 feet (1,000 m) long and 650 feet (200 m) across, and contains a mix of active and dormant vents.

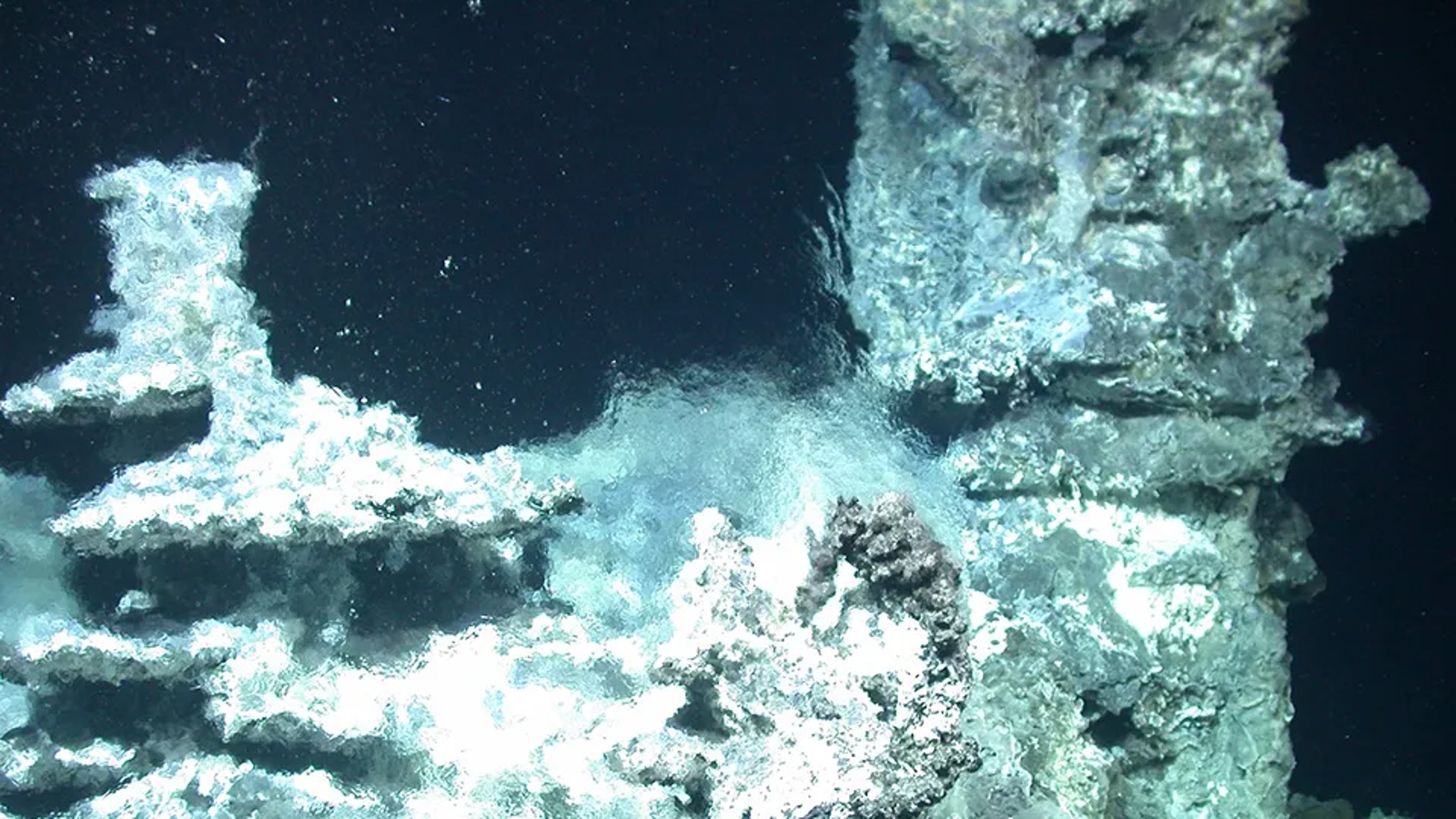

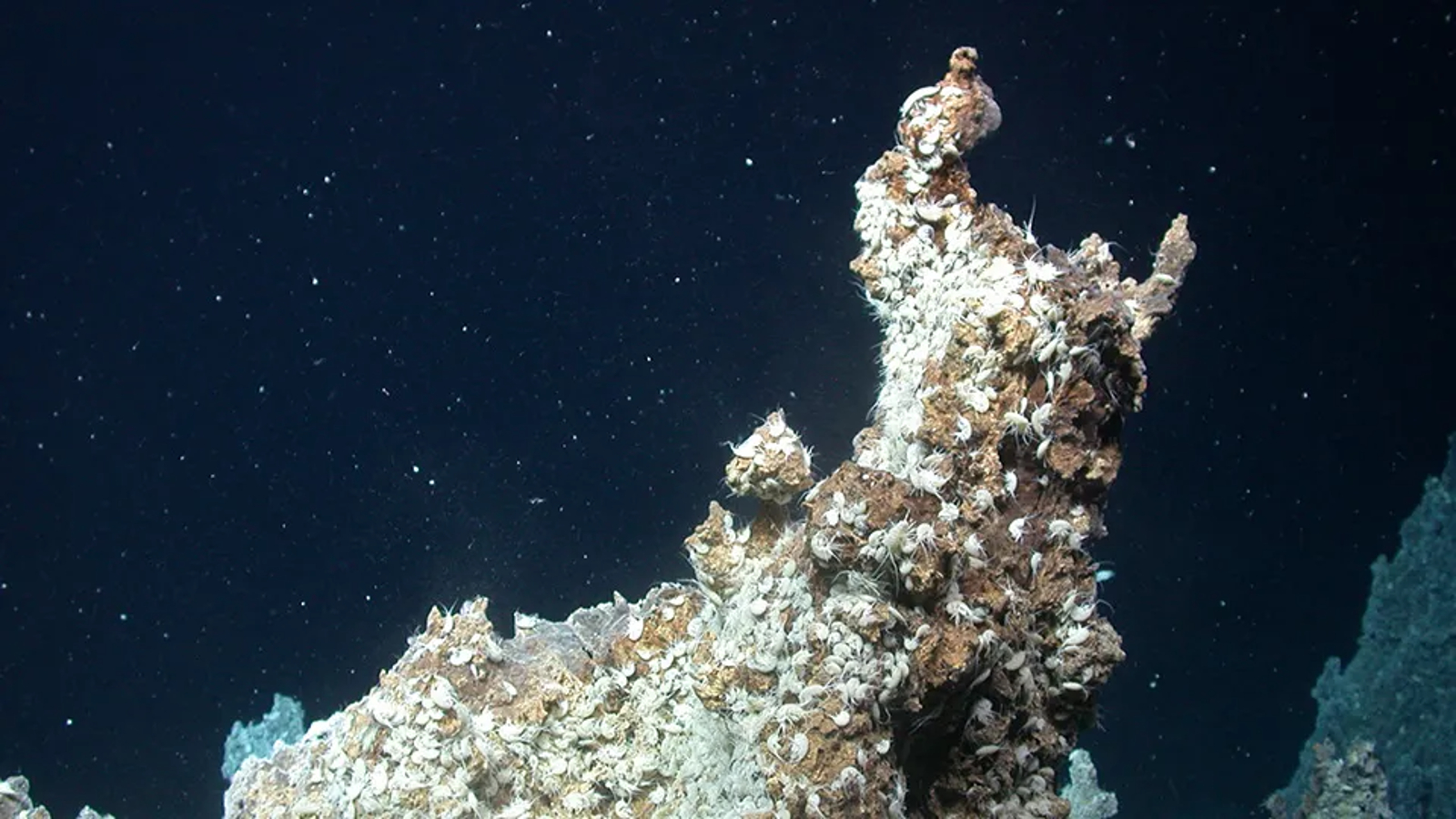

One of the largest vents, which has multiple chimneys and sprawling rocky branches, is named Yggdrasil after the cosmic tree of life that connects the nine realms of Norse mythology. Another set of vents, known as the Nidhogg spring, gets its name from the serpent-like dragon fabled to have lived in Yggdrasil and gnawed on its roots.

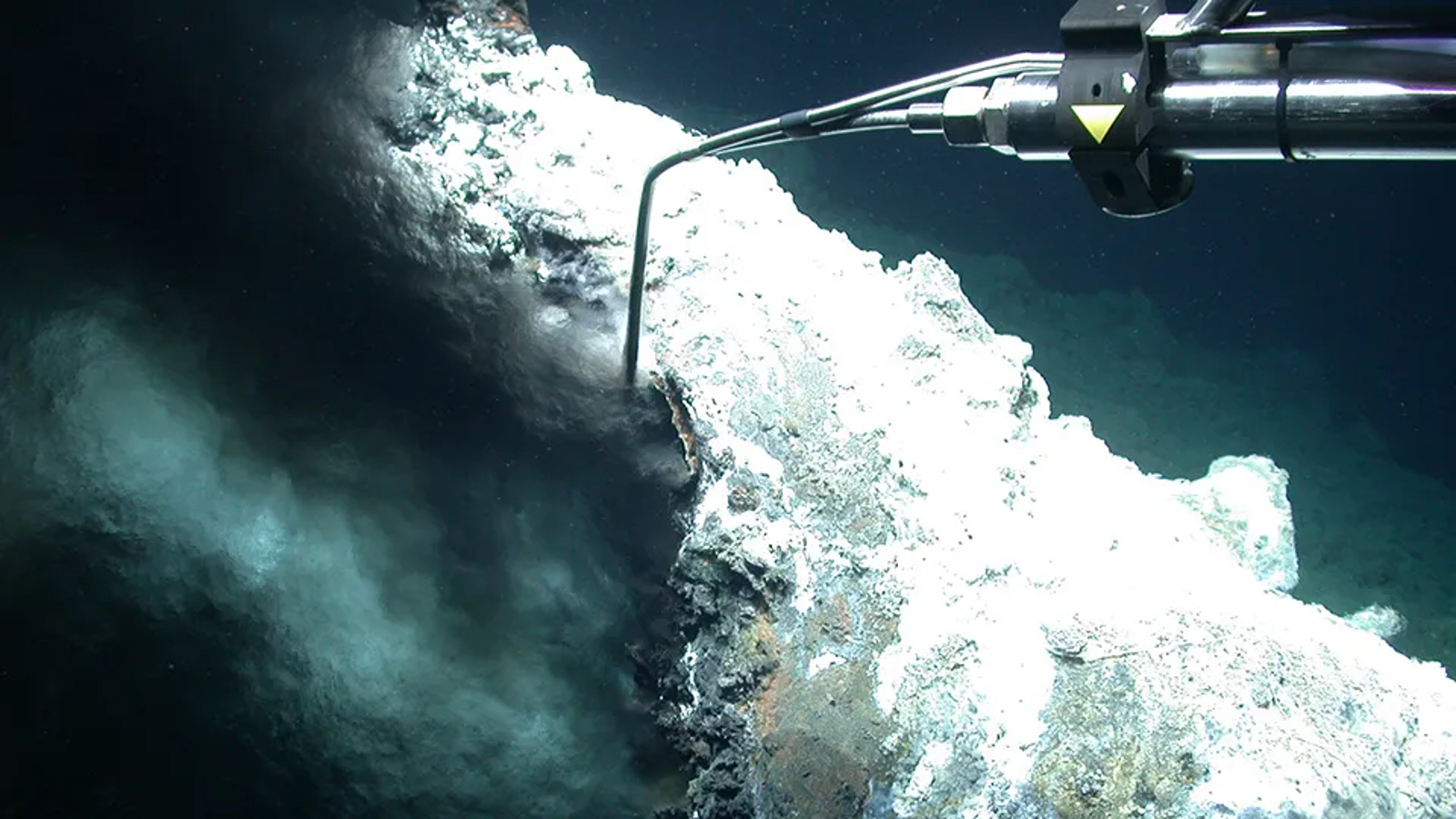

Researchers discovered the fantastical vents in 2022 during an expedition of the Knipovich Ridge — a 310-mile-long (500 kilometers) raised section of the seabed between Svalbard and Greenland. The researchers used remote underwater vehicles to photograph the vents and take samples of the water bubbling from the chimneys. Some of the outflows reached up to 572 degrees Fahrenheit (300 degrees Celsius).

The researchers published their findings from the expedition May 3 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Related: Hidden underworld filled with never-before-seen creatures discovered beneath the seafloor

The discovery was a big surprise because the Knipovich Ridge was previously believed to be geothermally dormant, the researchers wrote in a recent statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ridge is situated along the boundary between the North American and European tectonic plates. Normally, plate boundaries like this are a great place to find hydrothermal vents because they enable seawater to sink beneath Earth's crust, where it gets superheated by the magma in the mantle and rises back through the seafloor, creating the vents.

However, the Knipovich Ridge is what scientists refer to as "ultra-slow spreading," meaning the plates at this boundary move apart by less than 0.8 inches (2 centimeters) every year, researchers wrote. A 2015 study showed that most other plate boundaries move apart between two to four times faster.

As a result of this slow tectonic movement, scientists assumed that this region would be less geothermally active compared with other points along plate boundaries. But the new discovery shows this is not the case.

In addition to the unusual location, researchers noted there is uncertainty about many of the vents' other characteristics, including how old they are, what metals they contain, how much methane they pump into the ocean and which organisms thrive in these warm and chemically rich waters.

The research team is currently planning a return trip to the Jøtul hydrothermal field to help fill in some of the knowledge gaps about this newfound seafloor wonderland.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.