NASA spots sign of El Niño from space: 'If it's a big one, the globe will see record warming'

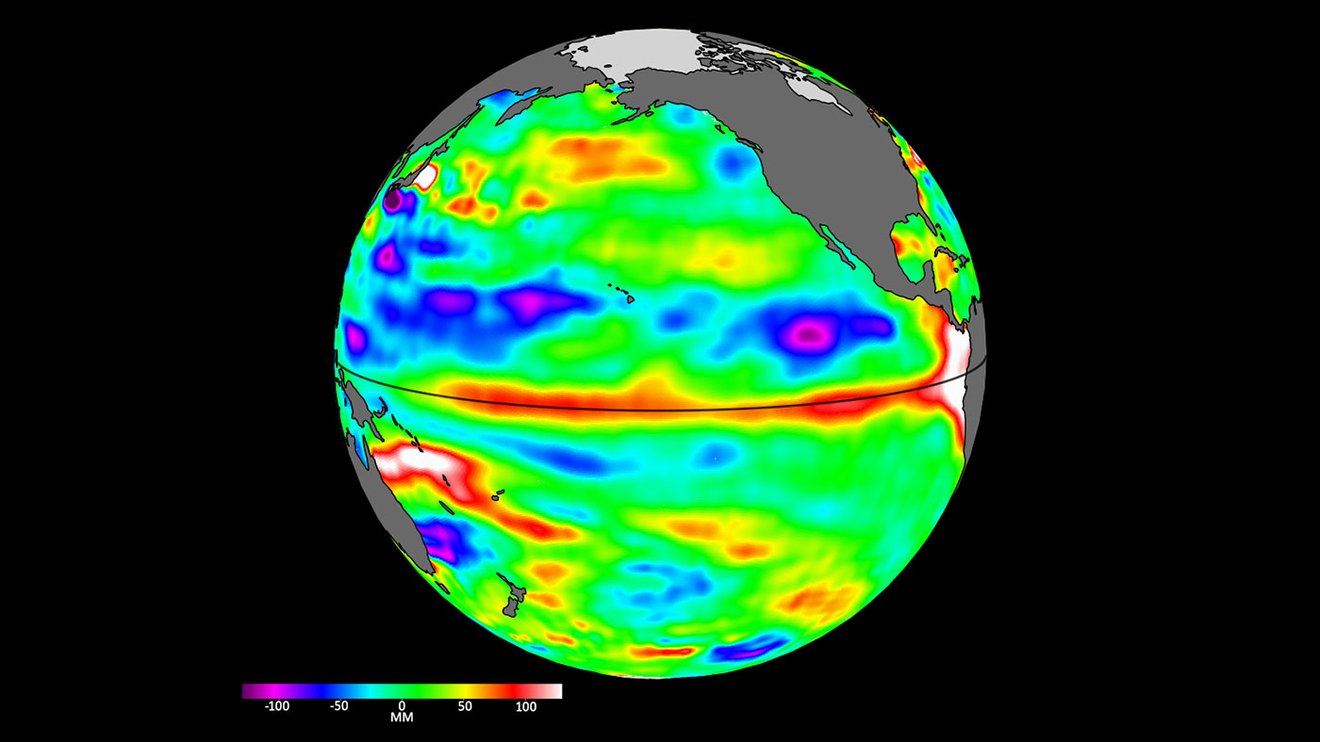

The Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite recorded Kelvin waves moving eastward across the Pacific — a phenomenon often considered a precursor to El Niño.

NASA has identified early signs of El Niño from space, after one of its satellites spotted warm water in the Pacific Ocean moving eastward toward the west coast of South America in March and April.

Data from the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite, which monitors sea levels, showed Kelvin waves moving across the Pacific. These long ocean waves are just 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 centimeters) high but are hundreds of miles wide. They are considered to be a precursor to El Niño when they form at the equator and move the warm upper layer of water to the western Pacific.

"We’ll be watching this El Niño like a hawk," Josh Willis, a project scientist on Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), said in a statement. "If it's a big one, the globe will see record warming."

How often does El Niño occur?

El Niño is a part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) climate cycle. Normally, prevailing easterly winds along the equator, known as trade winds, blow surface water west across the Pacific, moving warm water from South America towards Asia. As the warm water moves, cold water rises up to replace it.

El Niño is linked to weakened trade winds, causing the warm water to be pushed east.

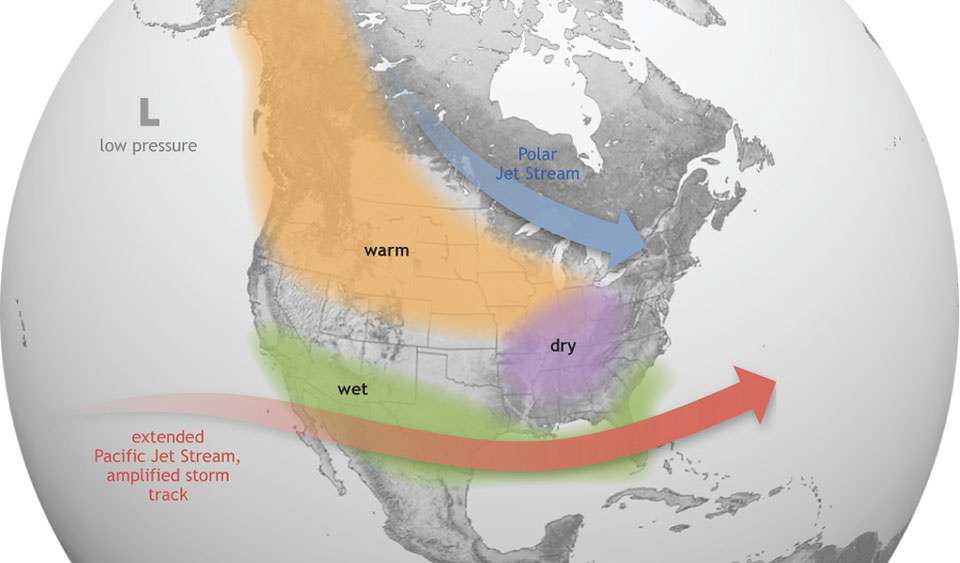

This causes a significant impact on weather patterns around the world. For the U.S., it means wetter weather in the southern parts and hotter weather in northwestern areas.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Its counterpart, La Niña, has the opposite effect, with strong trade winds pushing more warm water west.

El Niño normally hits once every three to five years, but it can occur more or less frequently. The last El Niño was in 2019 and lasted for six months, between February and August.

Is it an El Niño year?

On May 11, National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA) representatives said there was a 90% chance El Niño would hit this year and persist into the Northern Hemisphere's winter. According to NOAA's predictions, there is an 80% chance it will be at least a moderate El Niño — where ocean surface temperatures rise by 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius).

There is a 55% chance of a strong El Niño, with temperatures rising by 2.7 F (1.5 C), NOAA said.

A statement from JPL released May 12 said images taken by the Sentinel-6 satellite between the start of March and the end of April show Kelvin waves moving warm water east, pooling it off the coasts of Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. The red and white parts of the animation represent warmer water and higher sea levels.

"Ocean waves slosh heat around the planet, bringing heat and moisture to our coasts and changing our weather," Nadya Vinogradova Shiffer, NASA program scientist and manager for Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich, said in the statement.

The NOAA and NASA will continue to monitor conditions in the Pacific over the coming months to determine if and when El Niño will hit — and how strong it could be. "Here in the Southwest U.S. we could be looking at another wet winter, right on the heels of the soaking we got last winter," Willis said.

In April, scientists recorded the highest ever ocean surface temperatures, with the global average reaching 69.98 F (21.1 C). This record reflects the impact of climate change and the last La Niña coming to an end. "Now La Niña is over and the tropical Pacific, which is a huge expansive ocean, is warming up," Michael McPhaden, an oceanographer at the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, previously told Live Science.

Willis told Nature the combination of El Niño and supercharged ocean temperatures could mean a "string of record highs" in the next 12 months. “This coming year is gonna be a wild ride if the El Niño really takes off," he said.

Hannah Osborne is the planet Earth and animals editor at Live Science. Prior to Live Science, she worked for several years at Newsweek as the science editor. Before this she was science editor at International Business Times U.K. Hannah holds a master's in journalism from Goldsmith's, University of London.