Ocean's 'heart' is slowing down — and it will affect the entire planet's circulation

Melting ice could weaken Earth's strongest ocean current 20% by 2050, study reveals.

Melting Antarctic ice is slowing Earth's strongest ocean current, according to a new study.

The influx of cold meltwater could slow the Antarctic Circumpolar Current by up to 20% by 2050, researchers reported March 3 in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The slowdown could affect ocean temperatures, sea level rise and Antarctica's ecosystem, the team said.

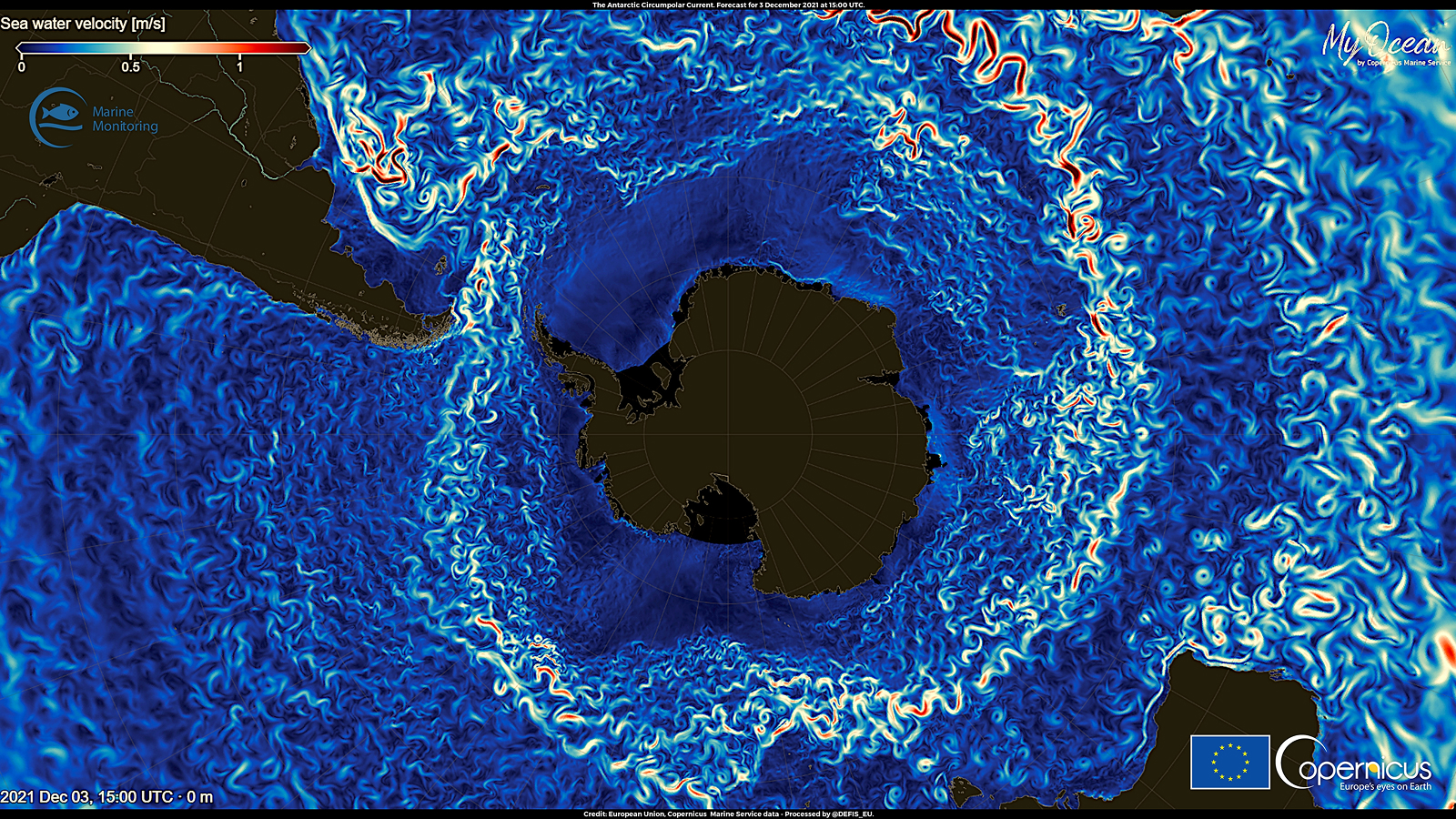

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which swirls clockwise around Antarctica, transports around a billion liters (264 million gallons) of water per second. It keeps warmer water away from the Antarctic Ice Sheet and connects the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian and Southern oceans, providing a pathway for heat exchange between these bodies of water.

Climate change has caused Antarctic ice to melt rapidly in recent years, adding an influx of fresh, cold water to the Southern Ocean. To explore how this influx will affect the Antarctic Circumpolar Current's strength and circulation, Bishakhdatta Gayen, a fluid mechanist at the University of Melbourne in Australia, and his colleagues used Australia's fastest supercomputer and climate simulator to model interactions between the ocean and the ice sheet.

Related: Are Atlantic Ocean currents weakening? A new study finds no, but other experts aren't so sure.

Fresh, cold meltwater likely weakens the current, the team found. The meltwater dilutes the surrounding seawater and slows convection between surface water and deep water near the ice sheet. Over time, the deep Southern Ocean will warm as convection brings less cold water from the surface. Meltwater also makes its way farther north before sinking. Together, these changes affect the density profile of the world's oceans, which drives the slowdown.

Such a slowdown could allow more warm water to reach the Antarctic Ice Sheet, thereby exacerbating the melting that's already been observed. In addition to contributing to sea level rise, this could add even more meltwater to the Southern Ocean and weaken the Antarctic Circumpolar Current further.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current also acts as a barrier against invasive species by directing non-native plants — and any animals hitching a ride on them — away from the continent. If the current slows or weakens, this barrier could become less effective.

"It's like a merry-go-round. It keeps on moving around and around, so it takes a longer time to come back to Antarctica," Gayen said. "If it slows down, what will happen is, things can migrate very quickly to the Antarctic coastline."

It's difficult to say when we'll start to feel the effects — if we haven't started feeling them already. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current hasn't been monitored very long because it's in such a remote location, Gayen told Live Science. To better differentiate warming-induced changes from baseline conditions, "we need a long-term record," he said.

The effects of the slowdown will be felt even in other oceans. "This is where the ocean heart sits," Gayen said. "If something stops there, or something different is happening, it's going to impact each and every ocean circulation."

Antarctica quiz: Test your knowledge on Earth's frozen continent

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.