Scientists say these North American rivers 'shouldn't exist.' Here's why they do.

At first glance, these waterways make no sense. A new review article details why they are the way they are.

Rivers join downstream, flow downhill, and eventually meet an ocean or terminal lake: These are fundamental rules of how waterways and basins are supposed to work. But rules are made to be broken. Sowby and Siegel lay out nine rivers and lakes in the Americas that defy hydrologic expectations.

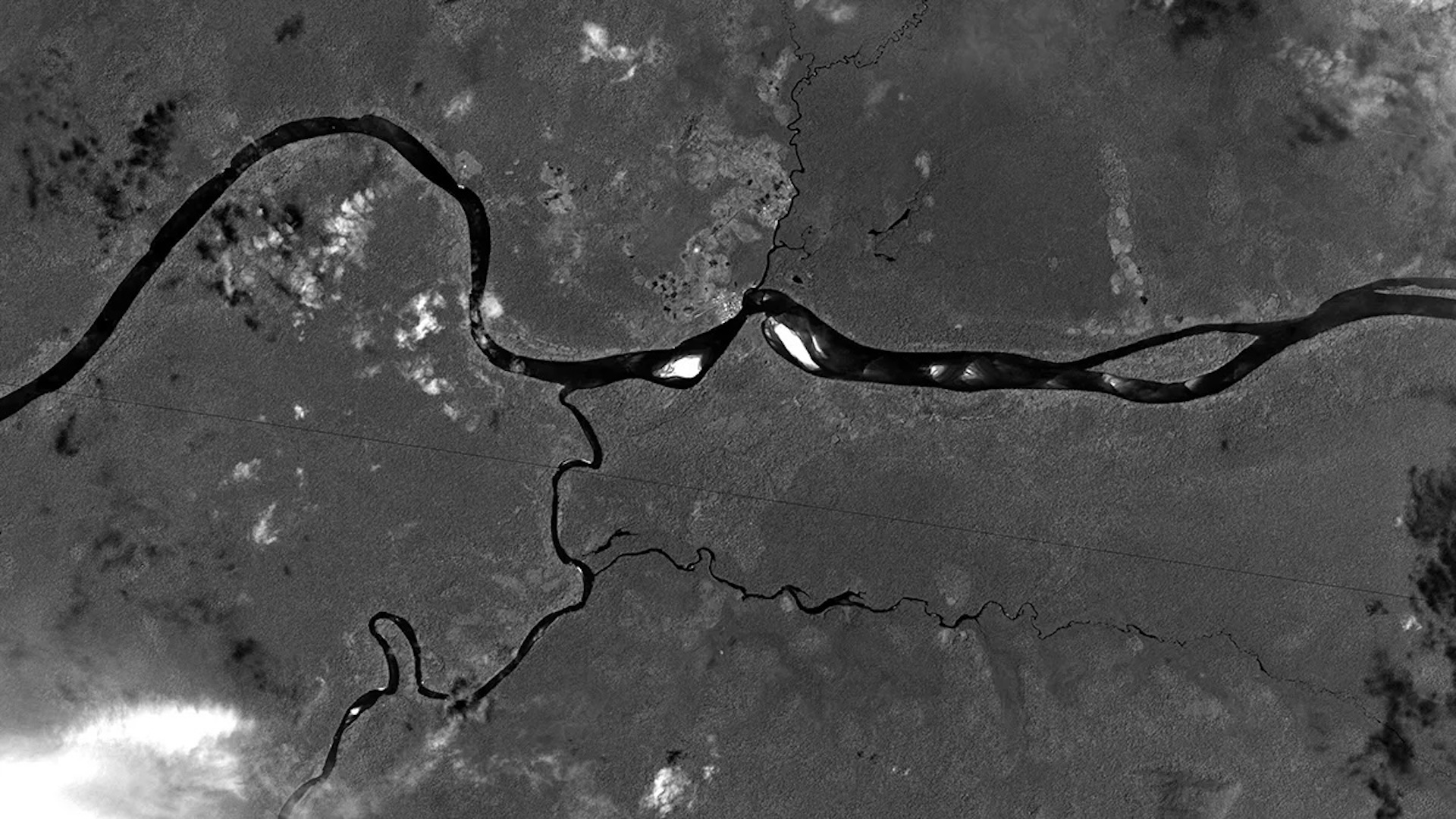

All exhibit instances of bifurcation, in which a river splits into branches that continue downstream. But unlike typical bifurcations, these examples do not return to the main waterway after branching off.

South America's Casiquiare River, for example, is a navigable waterway that connects the continent's two largest watersheds, the Orinoco and Amazon basins, by acting as a distributary of the former and a tributary of the latter. It's "the hydrologic equivalent of a wormhole between two galaxies," the authors write. The Casiquiare splits from the Orinoco River and meanders through lush, nearly flat rainforests to join the Rio Negro and, ultimately, the Amazon River. The study's authors point out that the slight slope (less than 0.009%) is enough to send large volumes of water down the river and that this unusual instance results from an incomplete river capture. They note that understanding of the Casiquiare is still evolving.

Related: Ocean's 'heart' is slowing down — and it will affect the entire planet's circulation

Dutch colonists first mapped the remote Wayambo River in Suriname in 1717. This river can flow either east or west, depending on rainfall and human modifications of flow using locks. It is also near gold and bauxite mining as well as oil production sites, and its two-way flow makes predicting the spread of pollutants difficult.

Of all the rivers they reviewed, the researchers described the Echimamish River, high in the Canadian wilderness, as the "most baffling." Its name means "water that flows both ways" in Cree. The river connects the Hayes River and the Nelson River, and by some accounts, the Echimamish flows outward from its middle toward both larger rivers. However, its course is flat and punctuated by beaver dams, leading to uncertainty, even today, about the direction of its flow and exactly where the direction shifts.

The authors also explored six other strange waterways, including lakes with two outlets and creeks that drain to both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. In doing so, they highlighted how much there is still to learn about how our world's waters work.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This article was originally published on Eos.org. Read the original article.

Rebecca Dzombak is a science writer and editor with a Ph.D. in Earth & Environmental Sciences. In addition to freelancing, she works on the American Geophysical Union's media team, where she covers all things Earth and space science.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.