Silver is being buried beneath the sea, and it's all because of climate change, study finds

For the first time, researchers have linked the amount of silver being buried in marine sediments to human-made climate change.

Global warming is burying huge amounts of silver beneath the South China Sea — and the same could be happening across the world's oceans, scientists say.

The amount of silver trapped in marine sediments off the coast of Vietnam has increased sharply since 1850, the new study shows. This coincides with the start of the Industrial Revolution, when humans began pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere on a large scale.

This is the first time research has highlighted a possible link between silver cycles in the ocean and global warming, study lead author Liqiang Xu, an associate professor in the department of geosciences at the Hefei University of Technology in China, told Live Science in an email. The discovery indicates global warming could have unknown impacts on other trace elements, too, Xu said. (Trace elements are elements like cobalt, zinc and iron that are present in tiny amounts in the environment but may serve as essential micronutrients for life.)

Like other elements, silver originates on land and enters the oceans primarily through weathering, where rainwater leaches elements from rocks and carries them into rivers.

Certain regions of the ocean are enriched with silver due to heavy river inputs, atmospheric dust, human emissions and hydrothermal vents. Silver in its ionic form (Ag+) is toxic for marine creatures, Xu said, but very little is known about how it interacts with wider ocean ecosystems.

Related: Cutting pollution from the shipping industry accidentally increased global warming, study suggests

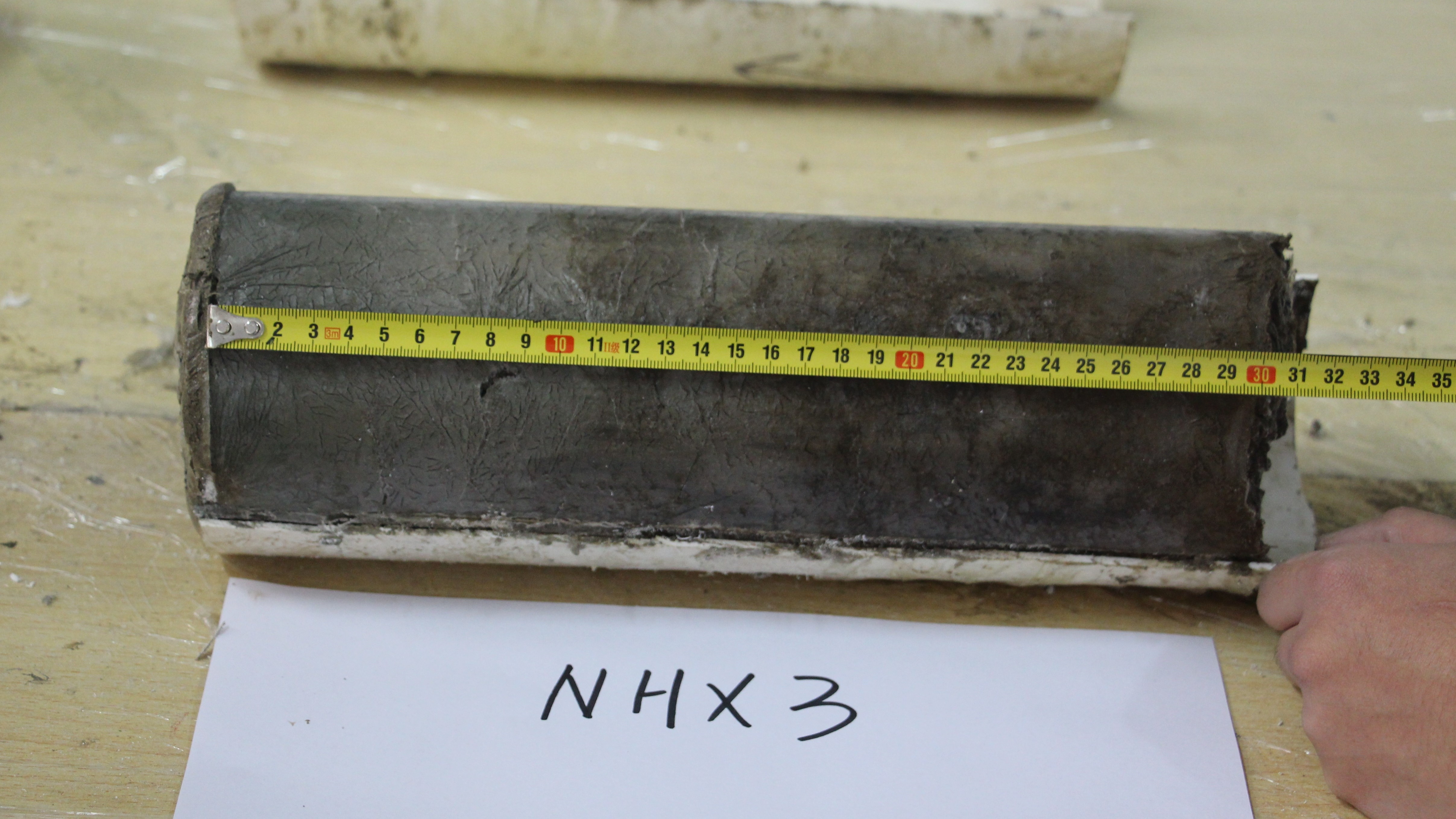

To find out more about how silver behaves in marine environments, Xu and his colleagues analyzed a sediment core from the Vietnam upwelling area in the eastern South China Sea. Upwelling areas are coastal regions where cold water rises from the seafloor, hauling up nutrients from the deep that sustain rich surface ecosystems.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The core was split into two zones, according to the study, published Aug. 13 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. Silver concentrations decreased from the base of the core, dating to roughly 1200 B.C., up to about 3 inches (7 centimeters) from the top. But the upper end of the core showed a very different trend.

"Burial of [silver] over the past 3,200 years shows an abrupt increase around 1850," the researchers wrote in the study. The timing is "in concordance with the atmospheric CO2 record," they added, suggesting that climate change accelerates silver burial in some marine sediments.

Concentrations of silver in upwelling areas are generally high, especially in areas where humans add more silver to the mix via industry and pollution, according to the study. Such areas include coastal Massachusetts and the San Francisco Bay, which researchers previously dubbed the "silver estuary."

Silver levels off the coast of Vietnam were naturally high and similar to levels previously recorded in upwelling areas off Canada, Mexico, Peru and Chile, Xu said. "However, these studies did not link the high concentrations with global warming," he said.

Global warming boosts water temperatures and coastal winds, which combine to increase the intensity of upwelling. This leads to more nutrients rising to the surface, increasing the abundance of algae that feed the entire food chain. High levels of dissolved silver in these regions could mean organisms absorb more silver than elsewhere. When they eventually die and sink, this silver drops down to the seafloor.

"Silver enters the sediments together with organic matter," Xu said. "Many upwellings strengthened as a result of global warming, and we believe silver in sediments of all these areas is increasing."

The authors of a 2021 review of trace metals in the ocean agreed that dead organisms may be transporting silver to the seafloor, although several other factors could also be at play, they said. For example, low oxygen levels might be boosting silver entrapment in sediments through chemical reactions, four of the authors told Live Science in an email.

"There is strong evidence that low-oxygen regions in the ocean are expanding," they said. "If silver trapping is increasing in these low-oxygen areas, it could indeed be happening on a broader scale."

If this is happening on a global scale, it could be a problem because the silver could potentially escape and poison ocean ecosystems, Xu said. "High levels of silver in sediments have a potential to be released to seawater," he said.

If the silver doesn't escape back into the water, it will eventually find its way to land, the authors of the review said. "Nothing is truly lost, only relocated," they said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus