'We know far more about the deep ocean than the moon or Mars,' says explorer Jon Copley

The deep sea, which encompasses waters deeper than 660 feet (200 meters), is home to alien-like creatures, but we know far more about these inky depths than people think, ocean explorer Jon Copley tells Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ocean explorer Jon Copley has completed dozens of dives to the darkest corners of the deep sea. Yet he is still amazed every time he encounters the strange life forms that thrive there. Over the past 25 years, Copley has traveled to the world's deepest hydrothermal vents, to Antarctica's icy "midnight zone" and to spectacular undersea mountain chains across the planet.

As a professor of ocean exploration and science communication at the University of Southampton in the U.K., Copley dedicates much of his time to addressing the myriad questions and myths surrounding the deep sea. His new book "Deep Sea: 10 Things You Should Know" (Orion Publishing, 2023) takes a fascinating look at some of the harshest habitats on Earth.

In a video interview with Live Science, Copley described the latest discoveries and where deep sea research is heading in a warming world.

Sascha Pare: Four years ago, when I was a student sitting in your deep sea ecology lectures, you had just published your first book, "Ask an Ocean Explorer" (Hodder & Stoughton, 2019). That book had 25 chapters, each answering a question that people commonly ask you as a deep sea biologist. What did you set out to do in "Deep Sea: 10 Things You Should Know"?

Related: Bizarre, alien-like creature discovered deep in Atlantic Ocean has 20 gangly arms

Jon Copley: This new book answers the top 10 questions that I know people have about the deep sea and also tackles some of the myths and popular misconceptions that we sometimes hear. The shorter format is an opportunity to focus and update the information — there have been quite a few discoveries in lots of different aspects of deep sea biology since I wrote "Ask an Ocean Explorer."

SP: Research has made great strides in recent years, I'm sure. What are some of the most exciting, new discoveries you discuss in the book?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

JC: We're finding out a lot more about how deep sea animals interact with each other and their environment. An area where we've seen a lot of interesting papers over the past five years has been in sensory ecology — realizing how animals perceive their environment, how they respond to that, how they avoid being seen by predators... It was nice to bring some of those together in a couple of the chapters.

SP: Some of the chapters focus on dispelling misconceptions people might have about what's down there in the ocean. What, to your mind, is the biggest, most pervasive myth about the deep sea?

JC: It's the idea that we know almost nothing about it. There's this very popular idea that we know more about the moon or Mars than the deep ocean. That's only really true for one very specific aspect of knowledge — having a detailed map of the terrain of its solid surface — because the moon and Mars are not covered in seawater, which blocks radar and means we have to use sonar in the deep ocean. Apart from that, we know far more about the deep ocean than those other places.

SP: The deep sea has attracted a lot of attention recently in the advent of deep sea mining. How worried are you about that?

JC: I think it's great that deep sea mining has made people care more about the deep ocean, but it hasn't actually started yet and research does not support some of the more hyperbolic headlines.

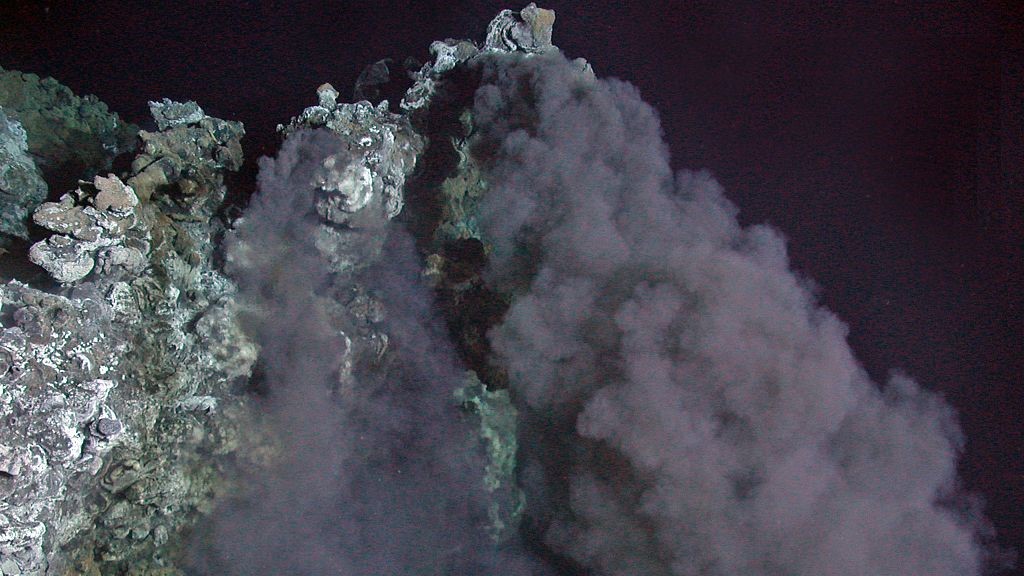

There's a lot of research focused on how we're going to manage mining, if it does go ahead. And there are some habitat types in the deep ocean that we don't need to do further research on, because we know they are so vulnerable. We know that we would risk species extinction at active hydrothermal vents, for example, because they're a tiny habitat globally — just 50 square kilometers [19 square miles] — with more than 400 animal species not found in any other habitat type. But I'm confident that we will see protection for active hydrothermal vents, because we scientists have been saying that for years.

SP: Deep sea mining is perhaps more manageable in terms of its impacts than other human activities. If not mining, what is the biggest human threat to the deep sea?

JC: To my mind, it's climate change. And it affects the deep ocean in lots of different ways. The one that concerns me particularly is deoxygenation — the reduction in oxygen levels — because deep sea animals need oxygen and they get it from the seawater.

Oxygen is carried down by currents that form in the polar regions and sink and spread throughout the deep ocean. As a result of climate change, the ocean is getting warmer and that means it can't carry as much dissolved oxygen. When water is warmer, the metabolism of things living in the water runs faster and they use up oxygen more quickly, so that makes the problem even worse. And thirdly, we know that the currents carrying oxygen down to the deep ocean are weakening, because melting ice sheets are making the water fresher and blocking the formation of dense water than sinks.

Those currents take centuries to complete their journey, which means the changes we have already made are going to carry on being felt for centuries. The deep ocean is already on track to have 10% less oxygen overall globally than it did in preindustrial times by 2400. It's hard to predict what the knock-on effects are going to be, but they are going to be widespread and they are coming.

SP: You dedicate much of your time to communicating deep sea science with lay audiences. Why is that so important to you?

JC: I enjoy talking to people about the deep sea because it's not somewhere we think about every day. We can go out at night and if we look at the sky, we might wonder about what's going on up there. But you can't glance into the deep sea in the same way, so it has become a realm of myth and darkness. Even the names of the deepest bits of the deep sea — the abyssal plains and the hadal zone — evoke that kind of underworld. It's nice to be able to shine a light on that for people and to highlight how our lives are connected to it.

SP: Speaking of the sky, how does exploring the deep ocean inform the search for life outside our solar system?

JC: Deep sea exploration has shown us that the range of conditions under which life can thrive is far greater than we imagined. The idea that chemosynthesis — where life is powered by a form of chemical energy instead of sunlight with photosynthesis — could sustain whole populations of animal species was impossible, until we discovered hydrothermal vents and other, similar habitats.

Deep sea vents also glow very faintly — too faintly for the human eye to see, but bright enough that microbes can use it as an energy source. Again, it expands our notion of what's possible in the cosmos, because you don't necessarily have to be that close to a bright star, potentially, to sustain life.

"Deep Sea: 10 Things You Should Know" is available in the U.K. to order on Amazon.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for length.

Deep sea creatures have evolved extreme strategies to cope with their environment. Read about the trials and tribulations of their sex lives in this excerpt from "Deep Sea: 10 Things You Should Know."

Deep Sea: 10 Things You Should Know - £10.11 at Amazon U.K.

In ten brief and informative essays, marine biologist and TV science advisor Professor Jon Copley journeys to one of the most mysterious and fascinating environments on Earth, the deep sea. Discover what makes this unique habitat such a challenging environment, the creatures that call it home and how ocean explorers are able to utilise the latest technology to aid their research and travel miles below the ocean surface.

"The Deep Sea: 10 things you should know" is a brilliant guide to one of the most fascinating and curious places known to humankind.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus