World's largest deep-sea coral reef found lurking beneath the Gulf Stream 'right on the doorstep' of US coast

A new deep-sea mapping project has revealed near-continuous reefs of cold-water corals spanning an area the size of Vermont just off the southeast U.S. coastline.

The world's largest deep-sea coral reef, which spans an area roughly the size of Vermont, has been uncovered "right on the doorstep" of the southeast U.S. coastline, new seafloor maps reveal. The dark-dwelling, ghostly corals likely support a wide variety of marine creatures that we didn't know were there, researchers say.

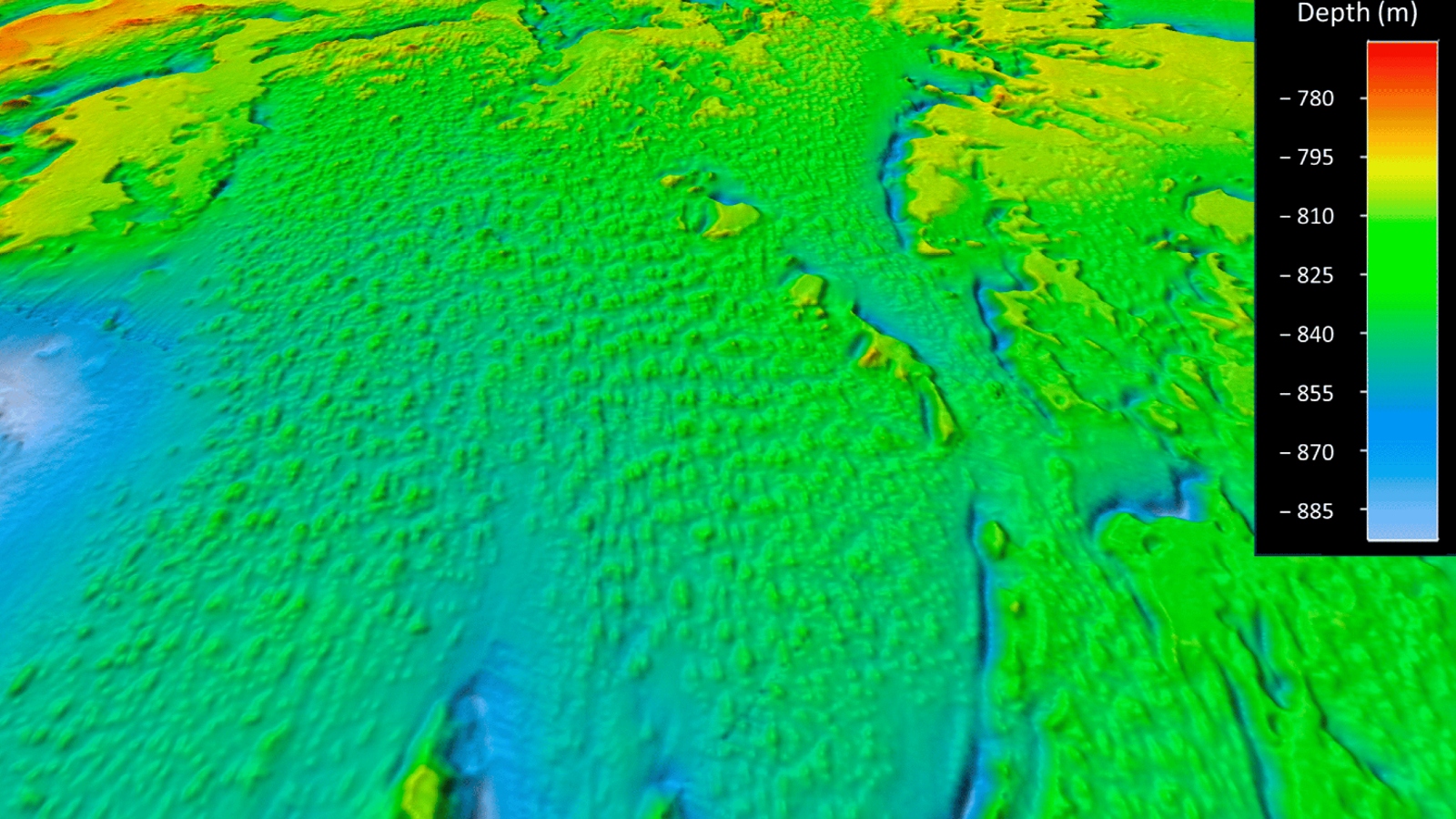

In a new study, published Jan. 12 in the journal Geomatics, scientists collated data from 31 multibeam sonar mapping surveys and 23 submersible dives to build a map of the Blake Plateau — a massive sloping shelf located around 100 miles (160 kilometers) off the U.S. coastline between North Carolina and Florida.

The new maps revealed thousands of previously unknown "mounds" of deep-sea corals, also known as cold-water corals, spread almost continuously across an area covering 6.4 million acres (2.6 million hectares) between 1,640 to 3,280 feet (500 to 1,000 meters) beneath the surface. The highest abundance of corals was located in an area the researchers dubbed "Million Mounds," which is around 158 miles (254 km) long and 26 miles (42 km) wide.

Related: 10 mind-boggling deep sea discoveries in 2023

The highly complex network of corals is "the largest deep-sea coral reef habitat discovered to date," researchers wrote in a statement.

Marine scientists have known that the Blake Plateau harbors deep-sea corals since the 1960s. But until now, they lacked the technology and funding required to properly assess how abundant they are, study lead author Derek Sowers, an oceanographer at the University of New Hampshire and mapping operations manager for the non-profit organization Ocean Exploration Trust, told Live Science in an email.

"We knew there would be many coral mounds to map here," Sowers said. But it was "impressive and surprising" to reveal just how many of the mounds there really were, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The coral expanse lies directly beneath the Gulf Stream — a deep, nutrient-rich current of warm water that runs northward along the eastern U.S. coast. The researchers believe this subsurface superhighway likely provides the corals with all the food they need to thrive in such large concentrations.

It's possible there could be even larger deep-sea coral reefs waiting to be found beneath other similar ocean currents across the world, Sowers said.

Related: What percentage of the ocean have we mapped?

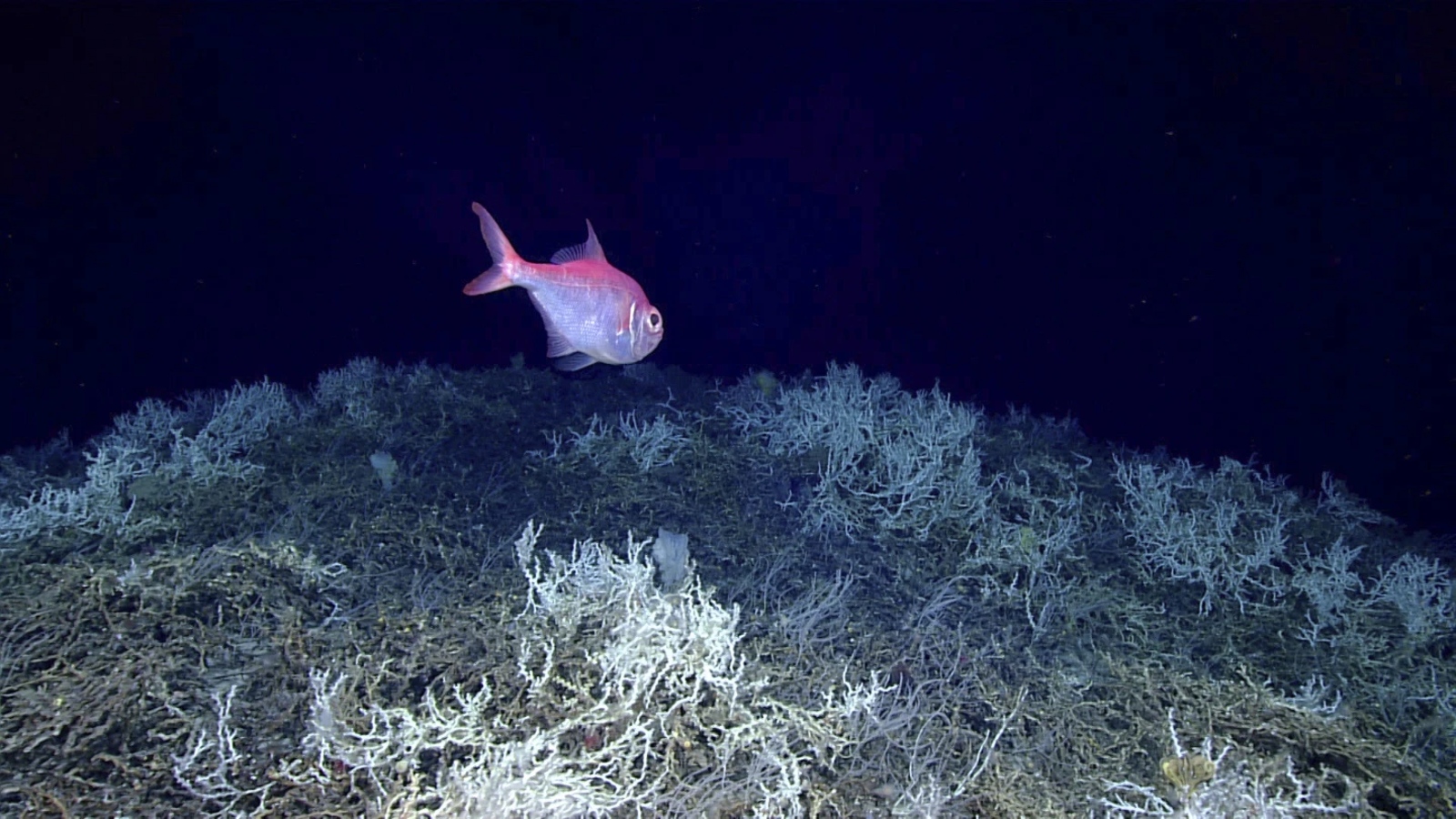

Deep-sea coral reefs are very different from tropical coral reefs. They dwell in waters that can reach as cold as 39 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) and can live for thousands of years.

Unlike tropical reefs, the deep-sea variants are mainly white because the cold water corals do not harbor the same colorful symbiotic algae that give their warm-water counterparts vibrant hues and provide them with energy via photosynthesis. As a result, they look very similar to tropical reefs that have experienced coral bleaching — a disease where heat-stressed corals expel their symbiotic algae and die off.

The newly discovered reefs are made predominantly of one species of coral, Desmophyllum pertusum (formerly known as Lophelia pertusa), with a small mix of other corals from the genera Enallopsammia and Madrepora. These few species provide a home to countless other creatures, including sharks, octopuses, crustaceans, swordfish, eels, sea stars, sponges and worms, as well as commercially important fish species like hake, Sowers said.

Most of the newly mapped reefs lie within a protected area, known as a Habitat Area of Particular Concern, which was created in 2010, Sowers said. This means the corals are shielded from destructive seafloor fishing practices that threaten other unprotected reefs around the globe, he added.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.