Scientists discover giant blobs deep inside Earth are 'evolving by themselves' — and we may finally know where they come from

Giant regions of the mantle where seismic waves slow down may have formed from subducted ocean crust, a new study finds.

We finally know where two giant blobs in Earth's middle layer came from — and they're a mismatched pair.

These strange regions in Earth's mantle, known as "large low velocity provinces" (LLVPs), are actually chunks of Earth's crust that have sunk into the mantle over the past billion years, new research suggests.

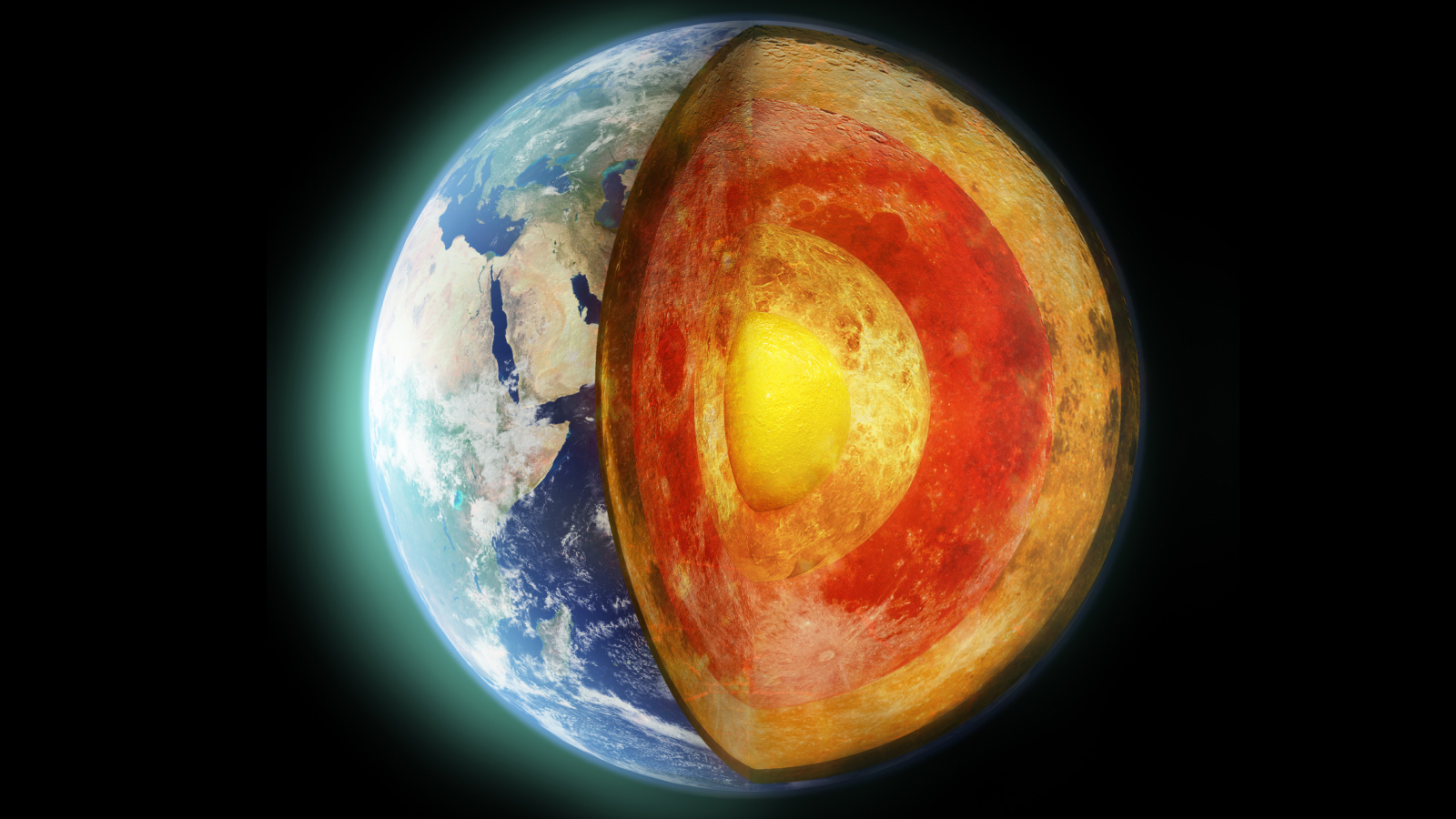

Scientists have long known that there are LLVPs — one below the Pacific Ocean and the other below Africa. In these regions, seismic waves from earthquakes travel 1% to 3% more slowly than they do in the rest of the mantle. Scientists believe they may affect the planet's magnetic field because of the way they influence heat flow from Earth's core.

There's a lot of debate about what LLVPs are. Some studies have suggested that they're material from the ancient Earth — either a layer of primordial unmixed rock from the planet's formation or a leftover hunk of the giant space rock that hit Earth 4.5 billion years ago, forming the moon.

Related: Scientists discover Earth's inner core isn't just slowing down — it's also changing shape

Others have suggested that the blobs are huge chunks of oceanic crust that were pushed into the mantle when one tectonic plate slipped under another — a process known as subduction.

The crust hypothesis had not been subject to as many studies as the ancient-material idea, said James Panton, a geodynamicist at Cardiff University in the U.K. In a new study, published Feb. 6 in the journal Scientific Reports, he and his colleagues used computer modeling to determine where subducted crust entered the mantle over the past billion years and to find out whether that subducted crust could form features similar to the LLVPs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We found that the recycling of the oceanic crust can indeed generate these LLVP-like regions beneath the Pacific and Africa without the need for a primordial dense layer at the base of the mantle," Panton told Live Science. "They are evolving by themselves, simply through the process of subduction of oceanic crust."

That doesn't mean there isn't dense material from Earth's youth at the bottom of the mantle, Panton said; there may be a thin layer of ancient material that contributes to the LLVPs as well. But if subduction alone can explain the LLVPs, that could hint at their age.

"That potentially means that shortly after we started having subduction on Earth, then maybe that's when we started to have LLVPs," Panton said. (The advent of subduction is itself a complicated question. Some scientists think it began more than 4 billion years ago, while others think it started around a billion years ago.)

The subduction process has resulted in two different types of blobs, the authors said in the study. The LLVP under Africa doesn't get as much crustal material currently as the LLVP under the Pacific, which is fed by the subduction zones of the Pacific Ring of Fire, which is a horseshoe-shaped line of subduction that circles the Pacific Ocean.

The African LLVP is thus older and better mixed with the rest of the crust, the team said. It also has less of a volcanic rock called basalt, which means it is less dense than the Pacific LLVP. This may explain why the African LLVP extends 342 miles (550 kilometers) higher in the mantle than the Pacific LLVP.

One question for the future, Panton said, is how hot regions of the mantle called mantle plumes may help drive the subduction process in the Pacific and influence the LLVPs. These plumes stretch from the very bottom of the mantle to volcanic hotspots at the surface, such as the Hawaiian islands.

What's inside Earth quiz: Test your knowledge of our planet's hidden layers

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.