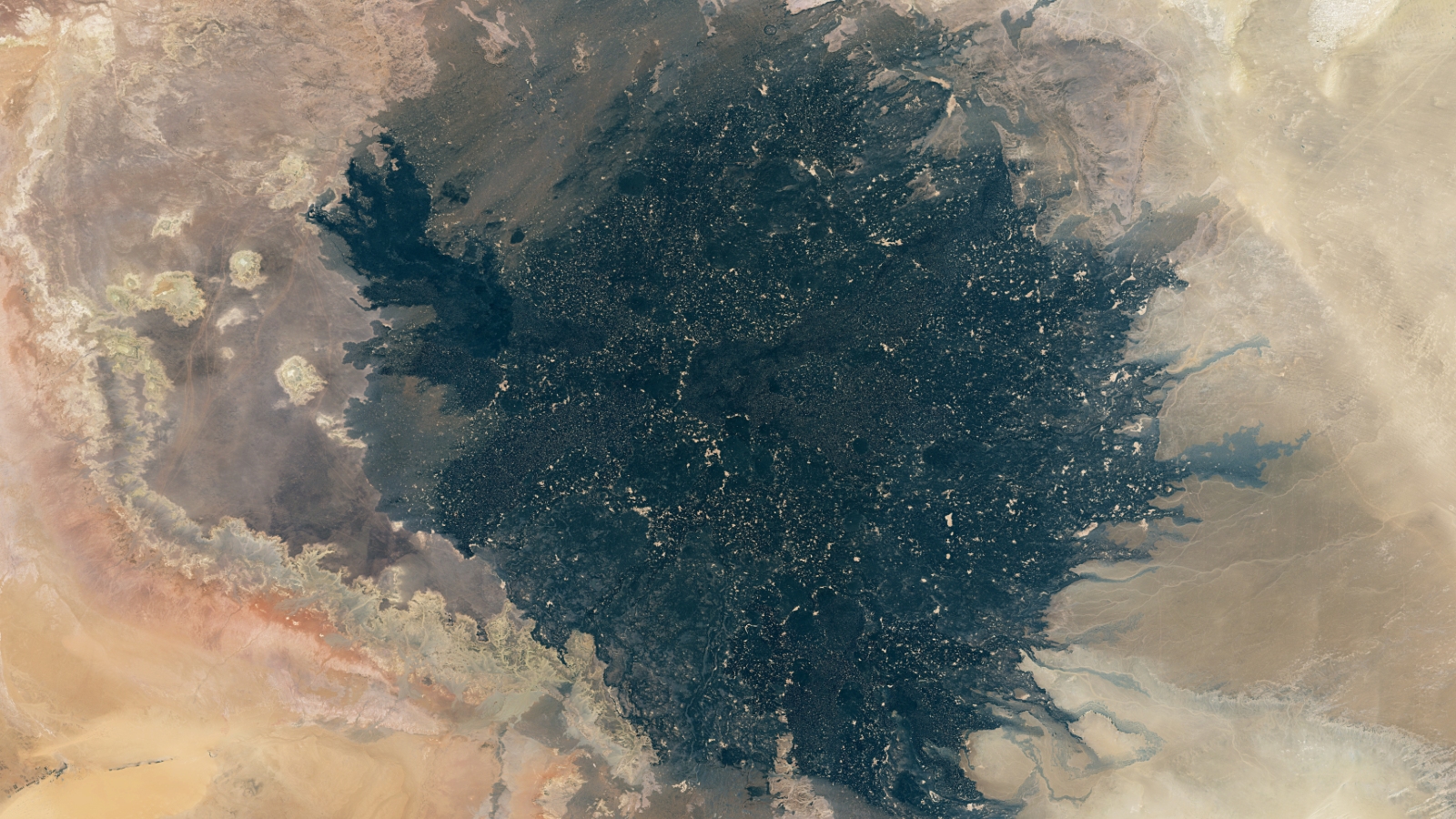

Earth from space: Massive field of ancient lava casts an eerie, gold-specked shadow in the Sahara

A stunning composite image, made up of three years' worth of satellite photos, shows the ancient lava of Libya's Haruj volcanic field interspersed with patches of golden sand.

Where is it? Haruj volcanic field, Libya [27.30184638, 17.50182896]

What's in the photo? An ancient lava flow in the middle of the Sahara desert

Which satellite took the photo? Landsat 8

When was it taken? Between July 24, 2013, and April 13, 2016

A giant patch of black, fossilized lava that was spewed across the Sahara desert over millions of years looks like an eerie, gold-speckled shadow in this stunning composite of three years' worth of satellite photos.

The shadowy mass, known as the Haruj volcanic field, covers around 17,000 square miles (44,000 square kilometers) in central Libya and contains roughly 150 extinct volcanoes, ranging from small vents and chimneys to larger shield volcanoes, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Some of the volcanic rocks are up to 6 million years old, while others were left by eruptions that happened as recently as a few thousand years ago, according to the Global Volcanism Program at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.

While the dark color of the petrified lava makes the field look smooth and flat from above, the field is extremely uneven, with areas where multiple eruptions have caused layers of rock to pile up above their surroundings. The site is also littered with raised vents and at least 30 cones that stand more than 330 feet (100 meters) tall, according to the Global Volcanism Program.

The tallest peak in the field stands roughly 3,900 feet (1,200 m) above sea level.

Related: See all the best images of Earth from space

The satellite image above is what is known as a "best pixel mosaic" and was made using a computer program that sorts through multiple images of the same spot pixel by pixel to create a final image that is free from obscuring elements, such as clouds or dust storms, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This model also selected pixels where patches of sand that have settled in between gaps in the lava catch the sunlight, which has created the golden speckles littered across the field. These sandy spots are much less obvious in other satellite images of the area.

Volcanic history

Most volcanoes are born along fault lines that intersect Earth's tectonic plates, because this is where the planet's crust is weakest and magma from the mantle can easily rise to the surface.

However, the Haruj volcanic field is not located near any known fault lines. Instead, the lava there was likely dragged up directly from the mantle by a surge of hot, rocky material — known as a mantle plume — which created a reservoir of magma below the field.

As a result, lava from the Haruj volcanoes would have slowly bubbled up and oozed out from the field's multiple vents, similar to modern eruptions that occur at Hawaii's Kilauea volcano, rather than being ejected in explosive eruptions, according to the Earth Observatory.

Some researchers think Haruj is made up of two separate volcanic fields: Al Haruj al Aswad, which is located in the north and contains much older lava; and Al Haruj al Abyad, which is located in the south and was created more recently. However, it is hard to tell where one of these fields ends and the other begins, so it is more commonly thought of as a single entity.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.