Earthquakes at massive Alaska volcano Mount Spurr ramp up again — and there's now a 50-50 chance of an eruption

Ten months of unrest at Mount Spurr could be a sign of an upcoming eruption from a side vent or, less likely, from the main crater.

A volcano in Alaska could be primed to erupt, which would likely send avalanches of hot ash and mud cascading down the mountain's slopes.

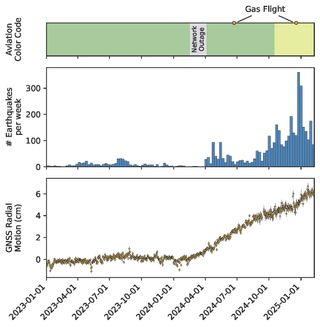

Mount Spurr, a snow-covered stratovolcano that sits 77 miles (124 kilometers) across the Cook Inlet from Anchorage, has been shuddering with small earthquakes since April 2024, according to the Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO). This activity is likely linked to new magma moving beneath the mountain. It's possible this movement could cease without an eruption, but the volcano may also be ready to blow, the AVO warned in an advisory.

"It’s had a higher-than-normal number of earthquakes for many months," Matt Haney, the scientist-in-charge of the AVO at the U.S. Geological Survey, told Live Science. "But over the past month, that itself increased, and also the location of the earthquakes changed."

The earthquakes migrated from near the mountain's peak to a new area about 2 miles (3 km) down the slope — near a side vent called Crater Peak. This vent last blew in 1992 and also produced an eruption in 1953. In both cases, the volcano belched out columns of ash 65,000 feet (20,000 meters) into the atmosphere. There's a 50-50 chance this could happen again, Haney said.

The other likely scenario is that the magma movement ends without any volcanic activity occurring. Mount Spurr has gotten restless before without erupting. For example, in 2004 and 2005, the volcano saw an increase in earthquakes, but it had quietened down by 2006, Haney said.

The least likely scenario is an eruption at the mountain's summit crater, which hasn't occurred at Mount Spurr in the last 5,000 years. Not only are summit crater eruptions less frequent, Haney said, the movement of the earthquakes toward Crater Peak suggests that the mountain probably won't blow its top — just its flank.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If an eruption does take place, the mountain could give off explosive blasts of ash and pyroclastic flows — avalanches of hot gas, ash and rock that move at over 200 mph (320 km/h). In addition, melting snow and ice might cause mudflows called lahars. A summit eruption would potentially involve lava flows from the crater.

Luckily, there aren't any communities in the potential path of lahars or pyroclastic flows, Haney said. For humans, the main impact of Mount Spurr's eruption would likely be ash. In 1992, the eruption at Crater Peak shut down Anchorage's airport and dusted the city with 0.1 inches (3 millimeters) of ash.

"Today there are even more flights coming in and out of the Anchorage airport, so if something like that were to happen that would be very disruptive, Haney said." A large ash cloud might also affect flights that traverse Alaska on their way between North America and Asia.

About three weeks before the 1992 eruption, the volcano's frequent earthquakes transformed into a consistent seismic signal called a tremor, Haney said. That's what he and his team are watching for now.

"If we saw this more long-duration shaking of the volcano in our seismic data, that would be a more clear indication that the unrest is progressing toward a more certain eruption," he said.

US volcano quiz: How many can you name in 10 minutes?

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Most Popular