Earth's newest 'baby' volcano is painting Iceland's Fagradalsfjall region with incandescent lava

An eruption opened a 1.7-mile-long fissure in the ground on Monday (June 10), with lava still spewing and flowing south towards the site of the region's last volcanic eruption.

Earth's newest volcano has been born via a brand new volcanic fissure that opened up on Iceland's Reykjanes peninsula, spewing fountains of molten rock from the ground.

The event marks the third year in a row that the underlying Fagradalsfjall lava field has erupted.

The latest eruption occurred on Monday (June 10) after several days of seismic activity. Scientists have recorded more than 7,000 earthquakes in the region since July 4, the largest of which was a magnitude 4.8 quake, according to a statement from the Icelandic Met Office.

"Look at that Icelandic baby 'cano [volcano] go," Robin George Andrews, a volcanologist and science writer, said in a Twitter post on Monday (July 10). "This is Earth's freshest coat of paint: incandescent molten rock being blasted skyward from a new Icelandic fissure."

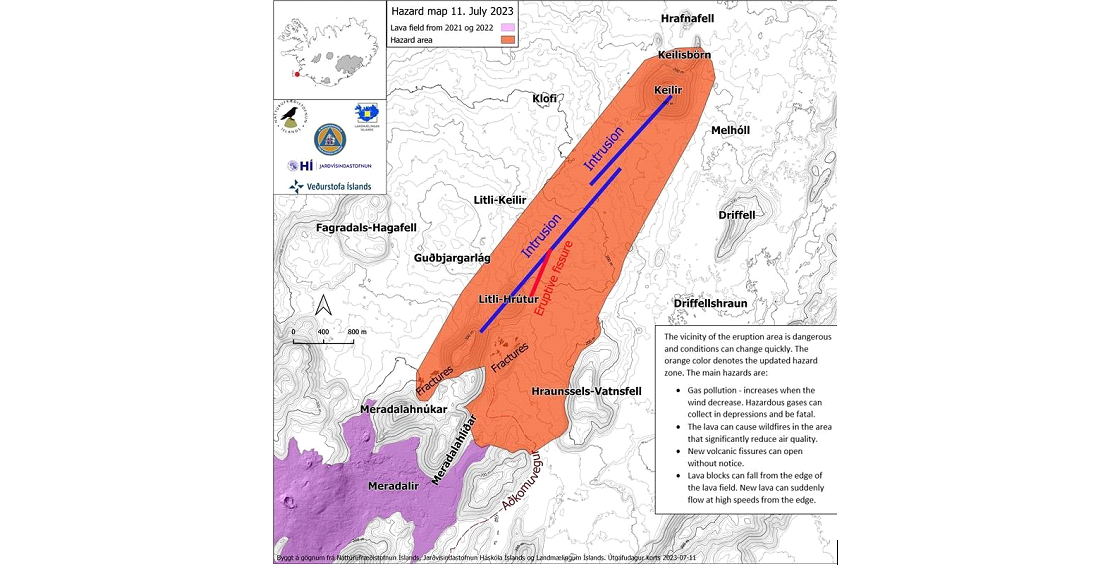

Lava is still trickling from the 1.7-mile-long (2.7 kilometers) fracture in the ground and flowing into a small, shallow valley to the southeast that could soon spill over. The surrounding area is uninhabited and the eruption poses no threat to infrastructure, according to the statement.

Related: The 12 biggest volcanic eruptions in recorded history

If the lava flow snakes southward beyond the small valley, it could reach the Merardalir valley, which is where the last Icelandic volcanic eruption occurred on Aug. 3, 2022. The year before that also saw a dramatic eruption on the Reykjanes peninsula that broke an 870-year-long quiet period in the Krýsuvík-Trölladyngja volcanic system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Here we go again!A volcano is erupting for the 3rd year in a row on the Reykjanes Peninsula, near Iceland's capital Reykjavik. Today marks 323 days since the 2022 eruption ended. The interval between the eruptions of 2021 and 2022 was 319 days... #Fagradalsfjall #Keilir pic.twitter.com/ynBRM4ikN7July 10, 2023

Scientists detected the first signs of the latest eruption in April via a small subsistence signal — a slight sinking of the ground potentially caused by an inflow of magma. The following sequence of earthquakes, which was similar to those recorded prior to the eruptions in 2021 and 2022, alerted the researchers that another eruption could be on the horizon.

Further monitoring revealed that a vertical sheet of magma, known as a "dike intrusion," was migrating upwards to the surface between the Keilir and Litli-Hrútur mountains. In 2022, the same phenomenon culminated in an eruption five days later.

On July 7, researchers calculated that 424 million cubic feet (12 million cubic meters) of magma — a similar volume as in 2022 and enough to fill 5,000 Olympic-size swimming pools — was brimming less than a mile (1.6 km) below the ground surface, fracturing Earth's crust.

The magmatic dike continued to inflate and inch upward until mid-afternoon on Monday, when it finally breached the surface and emerged "as a series of fountains," according to the statement.

The eruption has since decreased in intensity, with fewer, smaller lava jets. Seismic activity has also subsided.

Scientists are keeping a close eye on the lava flow's movements and warned that conditions can change quickly. "The lava can cause wildfires in the area that significantly reduce air quality," experts wrote in the statement. "New volcanic fissures can open without notice. Lava blocks can fall from the edge of the lava field. New lava can suddenly flow at high speeds from the edge."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.