Heat bursts from Iceland's recent eruptions in eerie NASA satellite image

Satellite images reveal the heat still radiating from the reawakened volcano in Iceland.

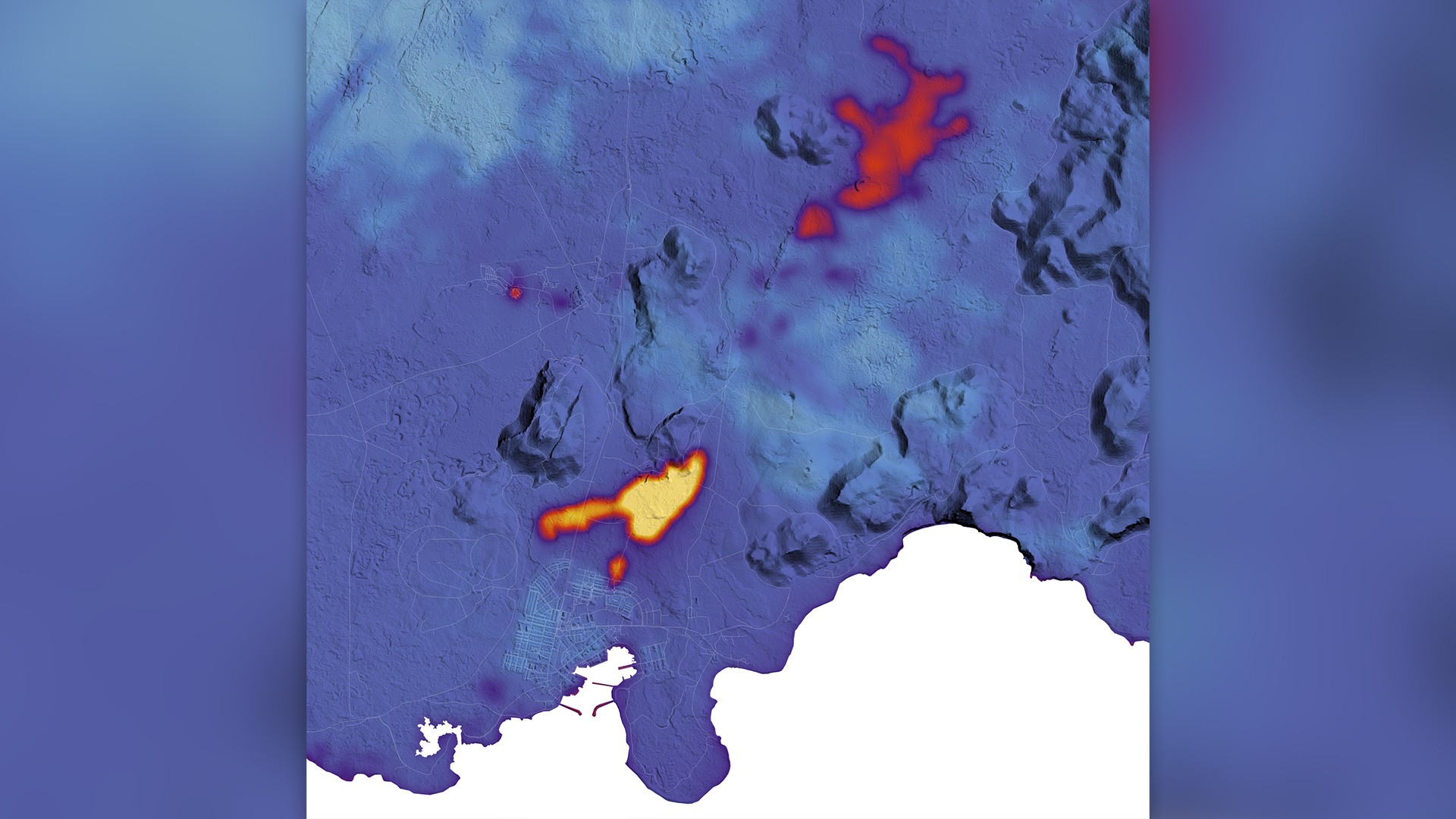

Eerie new NASA images have revealed the intense heat still emanating from the recently awakened volcano in Iceland.

On Jan. 14, a volcano in Iceland's southwestern Reykjanes Peninsula erupted again after a massive eruption in December. In the nearby fishing town of Grindavík, newly opened fissures spewed lava that triggered evacuations before engulfing houses and causing rolling blackouts in the area.

The recent NASA imagery, captured Jan. 16, shows the thermal signature of these lava flows as they poured from cracks in Earth's crust. By combining data from a thermal infrared sensor, a land-imaging satellite and elevation models of the area, scientists measured the amount of heat emanating from different regions in the eruption zone.

"A fissure eruption began at 7:57 a.m. local time on January 14, 2024, approximately 1 kilometer [0.6 miles] away from Grindavík," NASA representatives wrote. "Lava flows from the January 2024 eruption appear the warmest (yellow), while the still-warm December 2023 flows and the Blue Lagoon geothermal pool also stand out from the relatively cooler surrounding land."

The molten rock rising in the region is continuing to cause the ground beneath the volcanic area near Grindavík to push upward, but it is "too early" to tell whether the rate of land uplift has increased since prior to the eruption on Jan. 14, according to an update from the Icelandic Met Office on Jan. 19. A swarm of earthquakes preceded the initial eruption, but GPS data suggests that seismic activity has decreased in the area in the past few days.

This series of eruptions stems from a deluge of magma collecting below the Earth's surface, which has formed an underground path, or dike, that stretches for around 10 miles (16 kilometers) across the region. The accumulation of molten rock eventually blasted through the ground.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Construction workers have built large earthen dams and berms to divert the lava, but it's still unclear whether these measures will save Grindavík and the homes of its 3,500 residents, as well as a nearby geothermal power plant.

Though the latest eruption has ended, "there is still high danger of ground collapse into fissures within the town," the officials at the Icelandic Met Office wrote. Some experts believe more eruptions are on the horizon on the Reykjanes Peninsula — although they cannot predict when and where the next one will occur.

"We don't know where the next one is going to happen and we don't know how large it will be," Carmen Solana, an associate professor of volcanology and risk communication at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K., previously told Live Science. "That's the sad part of volcanology — we know that something is going to happen and you know roughly where, but you cannot pinpoint with that precision."

Kiley Price is a former Live Science staff writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Slate, Mongabay and more. She holds a bachelor's degree from Wake Forest University, where she studied biology and journalism, and has a master's degree from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.