'It was amazing': Scientists discover ash from 2 mystery volcanic eruptions in Wyoming

Scientists have found previously undocumented ash deposits buried beneath the Lava Creek Tuff in Wyoming — and at least one of them could be from an unknown volcanic eruption, they say.

Scientists in Wyoming have discovered evidence of two mysterious volcanic eruptions that are older than the last caldera-forming supereruption at Yellowstone.

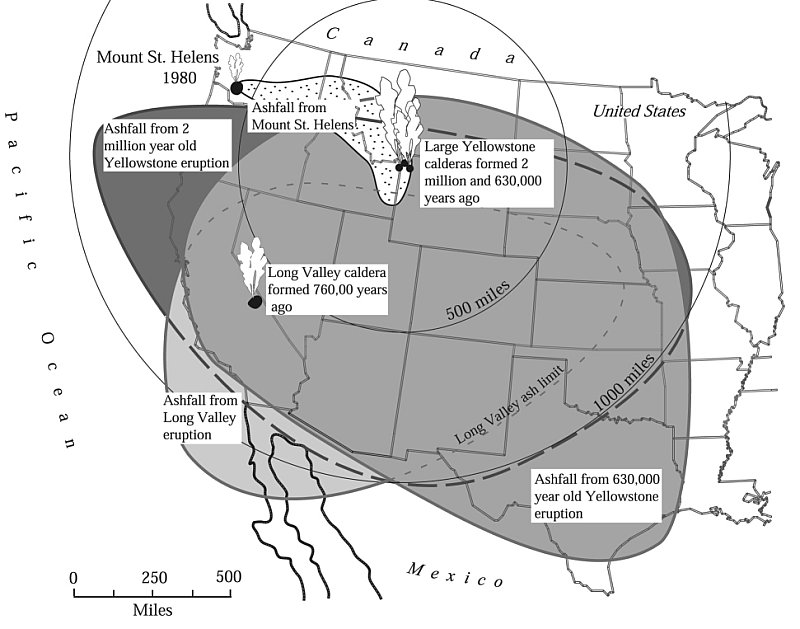

The ash deposits were buried beneath the Lava Creek Tuff, a large, white-ish mass of compacted volcanic ash formed from the last giant Yellowstone eruption 631,000 years ago. The origins of the newfound ash deposits are a mystery, but researchers hope to have answers by fall 2025, when they expect to receive test results from the samples.

"At first I just thought that the topography was complicated," Madison Myers, an associate professor of igneous processes at Montana State University who was on the field trip to Wyoming, told Live Science in an email. "But walking around we could clearly tell there were other units between the white ashfall layers [of the Lava Creek Tuff]. It was amazing."

The Lava Creek Tuff is made up of two distinct bodies of compacted ash, member A and member B, suggesting there was a change in the nature or composition of the volcanic material ejected during Yellowstone's last supereruption. The purpose of the field trip was to reevaluate evidence of the two members, Myers said, and the team were "shocked" to discover traces of unknown, older eruptions.

Related: We finally know where the Yellowstone volcano will erupt next

Because the ash deposits are buried beneath the Lava Creek Tuff, the eruptions that caused them must have occurred earlier than 631,000 years ago, according to an article written by Myers and her colleagues in the Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles.

The Yellowstone volcano is known to have produced two supereruptions before the Lava Creek Tuff eruption — the Mesa Falls Tuff eruption 1.3 million years ago and the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff eruption 2.1 million years ago — and it's possible that these blasts created the newfound ash deposits.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, early testing suggests the younger of the two ash deposits has no connection to Yellowstone. "One of the deposits we found contained biotite, a mineral not found in most Yellowstone eruptions," Myers said. "Thus we needed to think of a known large volume eruption that contained biotite."

The most likely suspect is the gargantuan Bishop Tuff eruption that formed Long Valley Caldera in California 767,000 years ago, Myers said.

Meanwhile, the origin of the older of the two ash deposits remains a complete mystery. It's possible that the ash came from an undocumented eruption, as it is relatively common for geologists to find deposits with dates that don't match known eruptions, according to Myers. "We recently had such an event happen in Yellowstone and are still trying to map and understand where this new undocumented eruption came from," she said.

The newly discovered deposits have not yet been dated, and the picture will become much clearer once those results come out, Myers said.

The best way to determine the origin of ash deposits is to date the mineral sanidine using a technique called argon geochronology. This technique measures the ratio of two different forms, or isotopes, of the element argon in samples. Argon 40, a stable isotope of argon, builds up in volcanic rocks at a predictable rate following an eruption, so scientists can determine the age of those rocks based on their argon 40 content.

Results from the argon dating will be available this summer at the earliest, Myers said, revealing the age, and therefore the likely origin, of both deposits. But another mystery will remain, she and her colleagues wrote, because it's unclear how so much ancient volcanic ash has stayed preserved in Wyoming.

"Likely these ashfalls were tucked in spaces that reduced exposure to wind and rain weathering," Myers said.

As well as discovering the two unexpected ash deposits, the researchers also achieved their original aim of finding evidence for two members in the Lava Creek Tuff. But this, too, turned out to be full of surprises.

"The Lava Creek Tuff deposit doesn't prove to us that there are two members of the Lava Creek Tuff eruption, but rather multiple magmas tapped and erupted through the course of the eruption," Myers said. "We are writing this up for publication now."

US Volcano quiz: How many can you name in 10 minutes?

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.