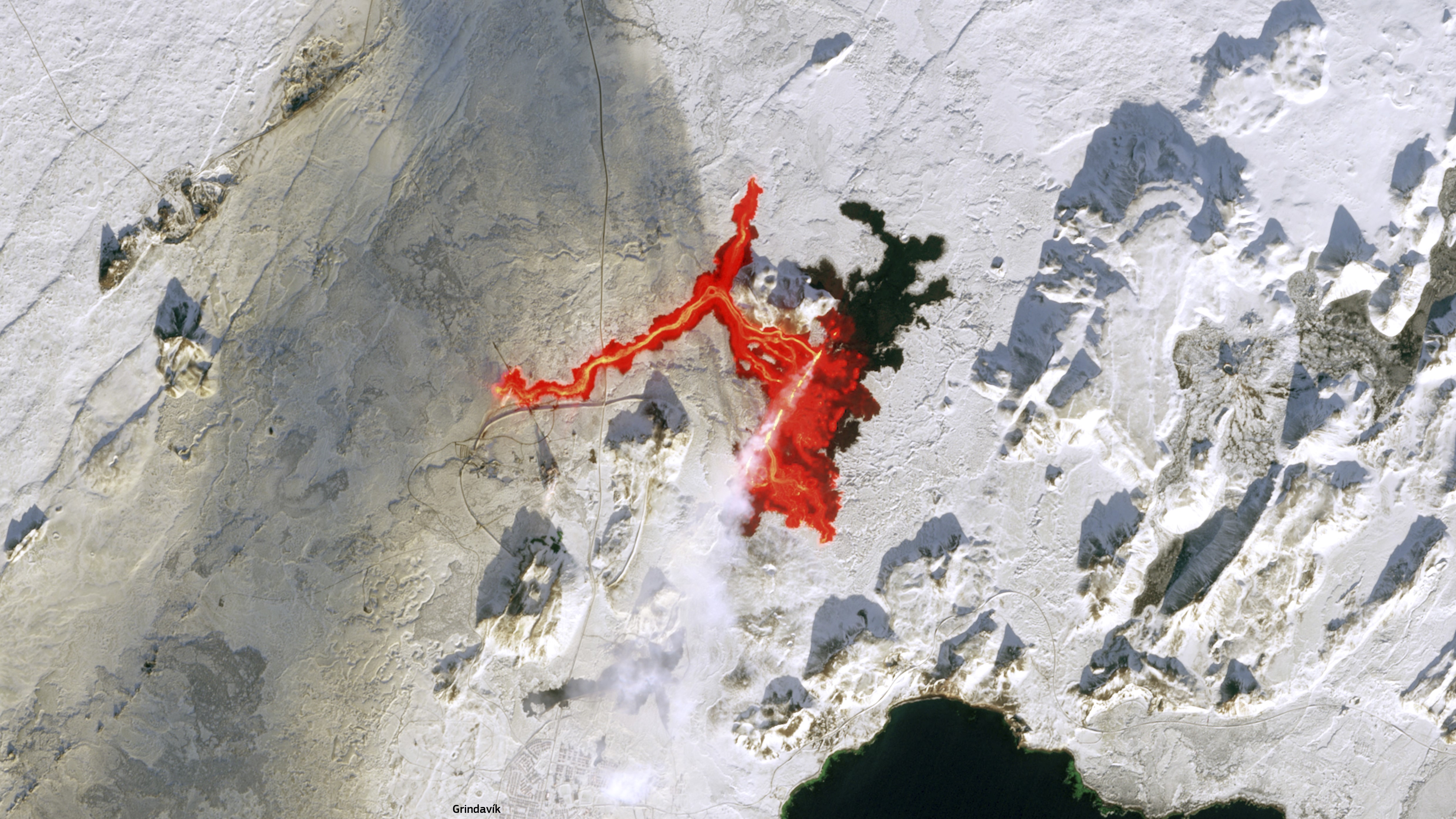

Lava bleeds from Iceland volcano into the frozen landscape in incredible satellite image

A volcano on Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula erupted for the third time in three months, sending lava 2.8 miles west from the huge fissure in Earth's surface.

Lava flowed like crimson blood from a massive tear in Earth's surface during the latest volcanic eruption on Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula, a dramatic new satellite image reveals.

The image, taken by the European Union's Copernicus' SENTINEL-2 satellite seven hours after the 1.9 mile (3 kilometers) fissure appeared, shows lava flows coursing 2.8 miles (4.5 km) west from the eruptive site, and a huge eruption plume extending southward from the peninsula into the Atlantic Ocean. "The smoke plume and the lava flow can clearly be seen near the city of Grindavik," according to a statement from the Copernicus team.

The volcano simmered down after staging its third eruption in three months yesterday (Feb. 8), according to the Icelandic Met Office (IMO). "The eruption is almost over, with no visible activity on the crater," Alberto Caracciolo, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Iceland's Institute of Earth Sciences, told Live Science in an email.

Unlike the previous eruption on Jan. 14, which opened fissures along the southern tip of the magma dike and propelled lava flows into Grindavík, yesterday's eruption occurred in the northern part of the dike closer to Svartsengi, 2.5 miles (4 km) north of Grindavík, Caracciolo said. With the eruption now dying down, it appears Grindavík will be safe this time around, he said — although the unstable ground beneath the town could lead to instances of "crack collapse."

The latest eruption followed a similar pattern to the two previous eruptions, the first of which occurred on Dec. 18, 2023. All three eruptions lasted around two days, Caracciolo said, with most of the magma extruded within less than 24 hours.

"The magma accumulated under Svartsengi before Feb. 8 was about 9 million cubic meters [318 million cubic feet]," Caracciolo said. "This does not mean that the entire estimated volume is going to erupt. Some magma can remain unerupted."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ground deformation has also diminished along the dike, indicating that magma is no longer rising to the surface at the same rate it was before the eruption, according to the IMO.

More eruptions are likely to occur in the coming months, according to Thorvaldur Thordarson, a professor of volcanology at the University of Iceland. "I can definitely see this happening a few more times," he told the Icelantic news website mbl.is. "It's something we can expect to continue throughout this year."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.