Mystery of Bolivian 'zombie' volcano finally solved

Uturuncu, a dormant volcano in Bolivia, appeared to be getting ready to erupt following earthquakes and "sombrero" shaped deformation — scientists have now worked out what's going on beneath the surface.

A "zombie" volcano in Bolivia has been rumbling in its sleep — despite being dormant for hundreds of thousands of years — and scientists now think they know why.

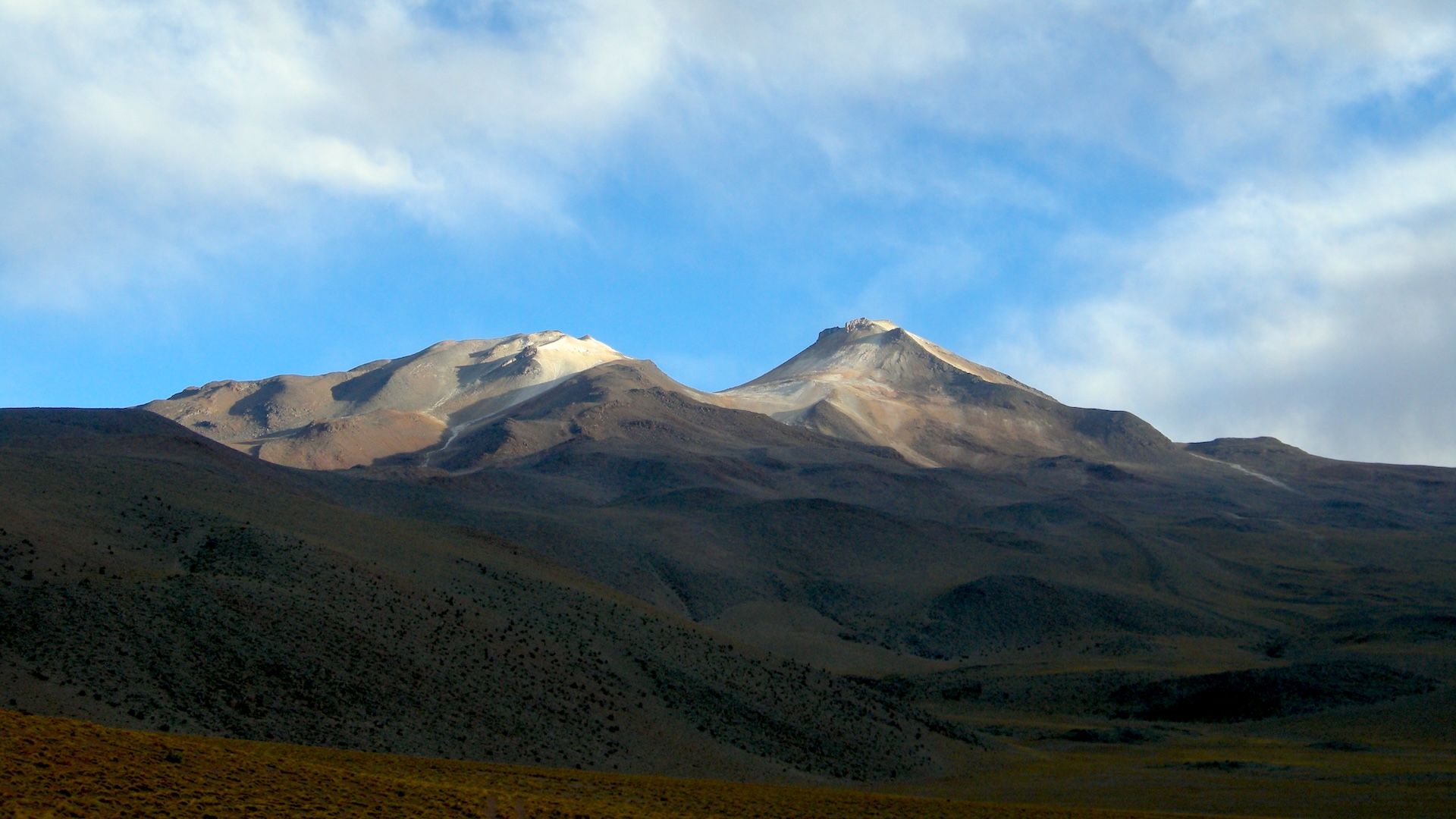

Uturuncu, located in the Andes in southwestern Bolivia, last erupted around 250,000 years ago. For several decades, it has been showing signs of unrest, releasing plumes of gas, shaking with earthquakes, and causing the surrounding ground to deform, leading to concerns it could be about to erupt.

However, according to a new study published Monday (April 28) in the journal PNAS, the unusual activity is down to the movement of liquid and gas beneath the mountain.

This "not only explains why a '"zombie'" volcano remains active but also offers insights into its eruption potential, establishing a technique that could be applied to help evaluate eruption hazards at other active volcanoes," the researchers wrote in the paper.

Uturuncu is a large, dormant volcano that stands at a height of 19,711 feet (6,008 meters) above sea level. It is a stratovolcano, which are large, steep, and cone-shaped volcanoes built up by many layers (strata) of hardened lava, volcanic ash, and rocks. Stratovolcano eruptions are often explosive because the lava is thick, meaning it traps gas easily. Mount St. Helens and Mount Vesuvius are both stratovolcanoes.

Related: Huge steam plume rises from Alaska's Mount Spurr as volcano edges closer to eruption

Uturuncu is known as a "zombie" volcano because of its ongoing, but noneruptive activity, the researchers wrote in the paper.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Since the 1990s, satellite radar and GPS measurements have shown that the ground around Uturuncu is deforming in a "sombrero" pattern, with a central region of rising ground surrounded by subsidence, or sinking. The central rising land has been uplifting for at least 50 years, at a varying rate of up to 0.4 inches (1 centimeter) per year.

This deformation, along with the frequent earthquakes recorded in the region and plumes of volcanic gases, especially carbon dioxide (CO2), being released from the volcano, led some scientists to theorize that there might be a huge magma body building underneath Uturuncu.

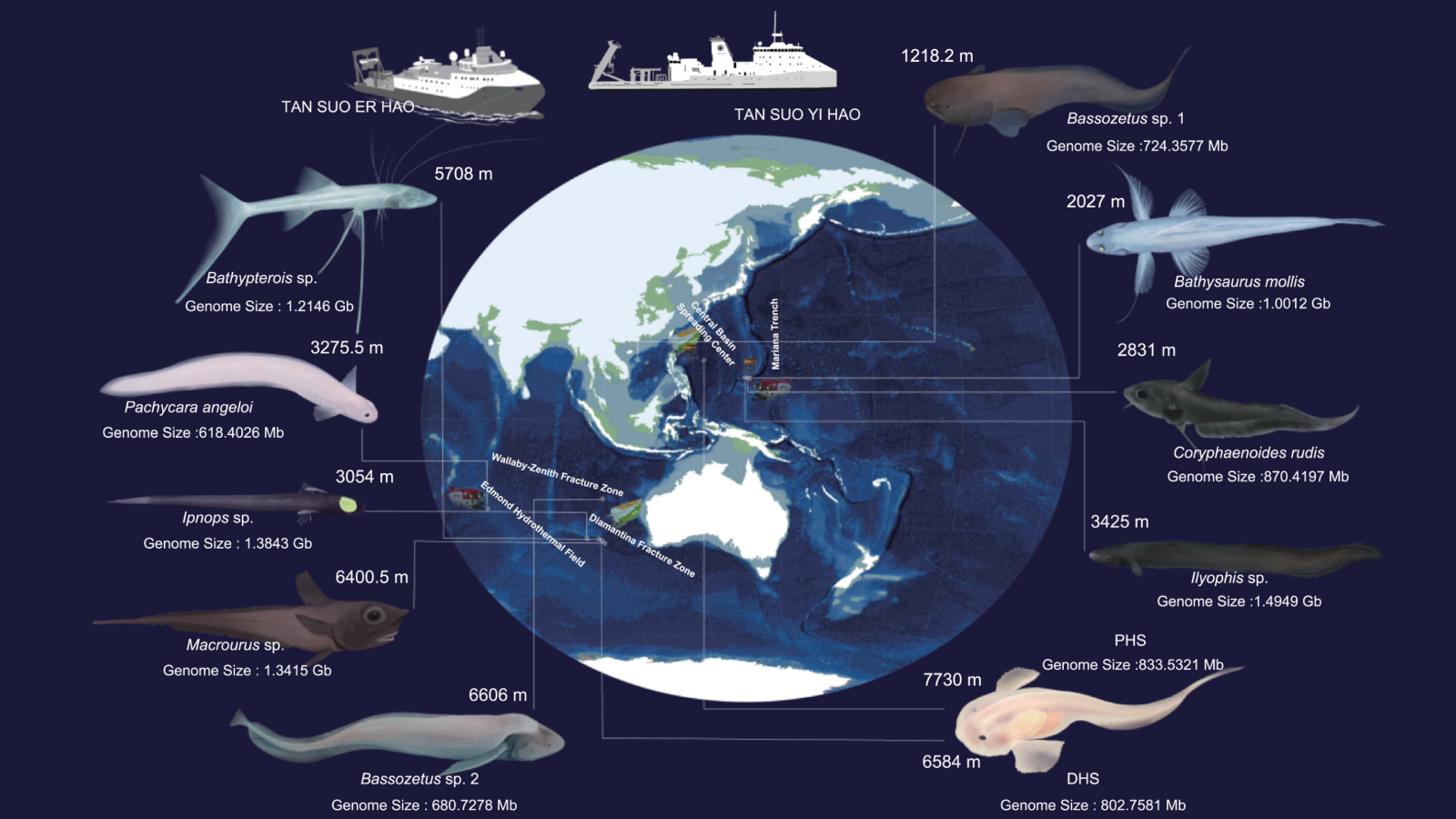

Cerro Uturuncu, right, and Cerro San Antonio, left, volcanoes above the small town of Quetena Chico on the Bolivian Altiplano.

Gravimeter and GPS station with Cerro Uturuncu in the background.

Uturuncu sits above an enormous and extremely deep underground reservoir of magma named the Altiplano-Puna Magma Body (APMB), which stretches beneath southern Bolivia, northern Chile, and northern Argentina. Magma from the APMB can be pushed upward and accumulate near the surface.

The presence of a body of magma beneath the volcano could indicate that Uturuncu may be gearing up to erupt.

In the new study, researchers analyzed signals from over 1,700 earthquakes to visualize what was occurring beneath the volcano, and also examined the properties of the rocks on and around the volcano to determine how seismic signals might interact with the ground.

Rather than an accumulation of magma, they found that the APMB is sending hot fluids and gases upwards towards the surface via a narrow chimney-like pipe. This causes gases like steam and CO2 to get trapped under the summit, and briny water to spread sideways into cracks around the volcano.

The observed ground deformation and earthquakes around Uturuncu can be explained by these fluids and gases moving around below the surface, rather than magma rising quickly from below, meaning that the volcano is not primed to erupt as previously feared.

This discovery could also help researchers determine if other volcanoes around the world are primed to erupt.

"The methods in this paper could be applied to the more than 1,400 potentially active volcanoes and to the dozens of volcanoes like Uturuncu that aren't considered active but that show signs of life — other potential zombie volcanoes," co-author Matthew Pritchard, a professor of geophysics at Cornell University, said in a statement.

Jess Thomson is a freelance journalist. She previously worked as a science reporter for Newsweek, and has also written for publications including VICE, The Guardian, The Cut, and Inverse. Jess holds a Biological Sciences degree from the University of Oxford, where she specialised in animal behavior and ecology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.