History has seen some monstrous volcanic eruptions, from Mount Pinatubo's weather-cooling burp to the explosion of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai on the island nation of Tonga.

The power of such eruptions is measured using the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), a classification system developed in the 1980 that's similar to the magnitude scale for earthquakes. The scale goes from 1 to 8, and each succeeding VEI is 10 times greater than the last.

There haven't been any VEI-8 volcanoes in the last 10,000 years, but human history has seen some powerful and devastating eruptions. Because it's extremely difficult for scientists to be able to rank the strength of eruptions in the same VEI category, here we present 11 of the most powerful volcanic eruptions in recorded history, meaning over the last 4,000 years, plus one VEI-8 eruption that happened in the distant past.

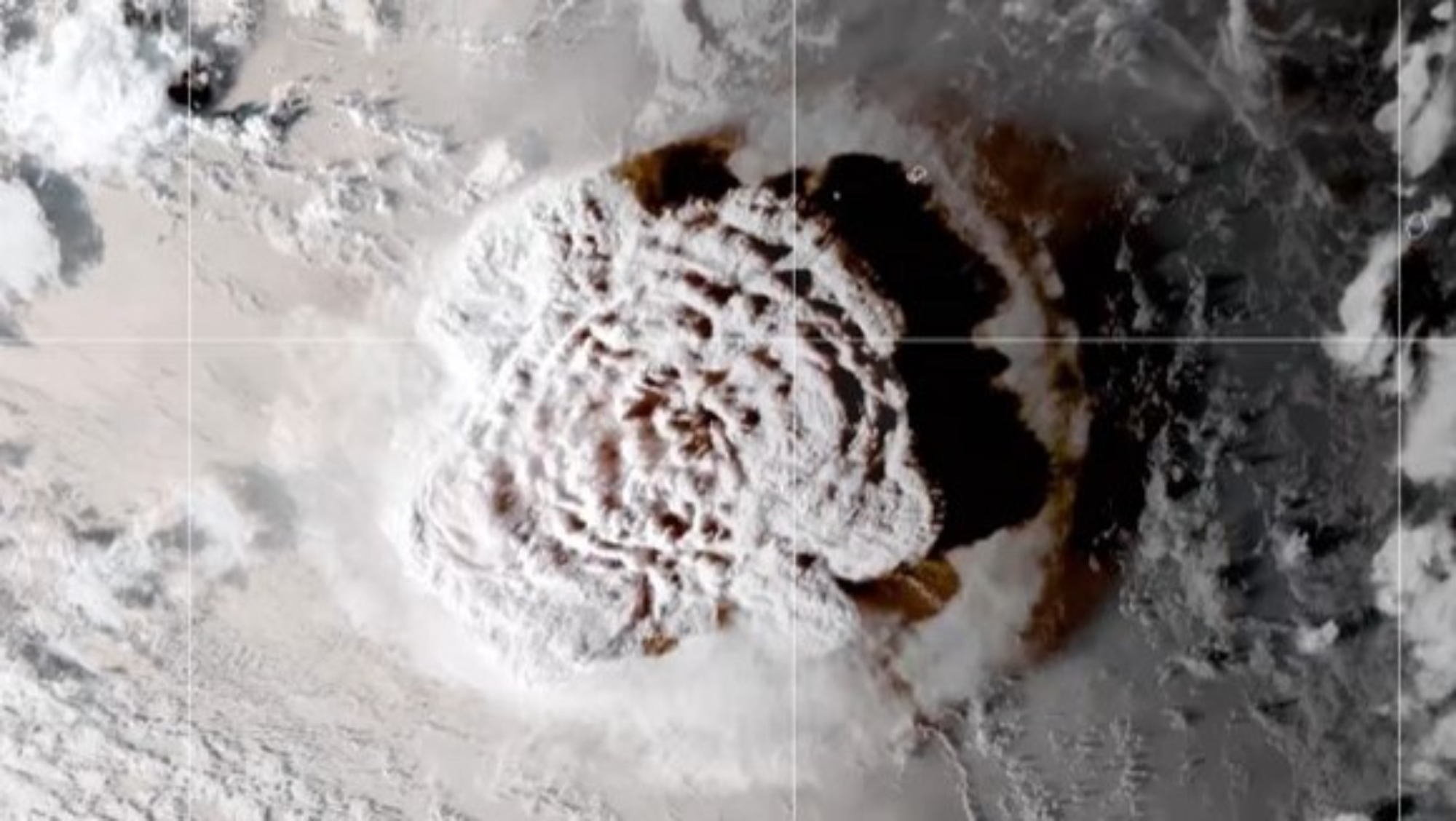

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, 2022 (VEI 5.7)

The Kingdom of Tonga, located in the South Pacific, experienced one of the biggest eruptions in recorded history in 2022. The submarine volcano first began to rumble in December 2021, the eruption started on Jan. 13, 2022 and it reached its steamy climax on Jan. 15, 2022.

Because the volcano is underwater, seawater that came into contact with the erupting magma was instantly superheated. As a result, the blast, which measured a VEI 5.7, injected 50 million tons (45 million metric tons) of water vapor into the atmosphere, or enough to warm the planet for years. The blast extended for 162 miles (260 kilometers) and a pillar of ash, steam and gas stretched 12 miles (20 km) into the air, the tallest in recorded history, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The giant blast released energy equivalent to more than 100 Hiroshima bombs, NASA said.

Huaynaputina, 1600 (VEI 6)

This peak was the site of South America's largest volcanic eruption in recorded history, in the year 1600. The explosion sent mudflows as far as the Pacific Ocean, 75 miles (120 km) away, and appears to have affected the global climate. The summers following the 1600 eruption were some of the coldest in 500 years. Ash from the explosion buried a 20-square-mile area (50 square kilometers) to the mountain's west, which remains blanketed to this day.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although Huaynaputina, in Peru, is a lofty 16,000 feet (4,850 meters), it's somewhat sneaky as volcanoes go. It stands along the edge of a deep canyon, and its peak doesn't have the dramatic silhouette often associated with volcanoes.

The 1600 cataclysm damaged the nearby cities of Arequipa and Moquengua, which only fully recovered more than a century later, according to the Smithsonian Institution.

Krakatoa, 1883 (VEI 6)

The rumblings of Krakatoa (also spelled Krakatau) in the weeks and months of the summer of 1883 finally climaxed with a massive explosion on April 26 and 27. The explosive eruption of this stratovolcano, situated along a volcanic island arc at the subduction zone where the Eurasian plate meets the Indo-Australian plate, ejected huge amounts of rock, ash and pumice. The final blast was the loudest recorded sound in history, and could be heard on 10% of Earth's surface, according NOAA.

The explosion also created a tsunami, whose maximum wave heights reached 140 feet (40 meters) and killed about 36,000 people. Tidal gauges more than 7,000 miles (11,000 km) away on the Arabian Peninsula even registered the increase in wave heights.

While the island that once hosted Krakatoa was completely destroyed in the eruption, new eruptions beginning in December 1927 built the Anak Krakatau ("Child of Krakatau") cone in the center of the caldera produced by the 1883 eruption. Anak Krakatau sporadically comes to life, building a new island in the shadow of its parent. It last erupted in February 2022.

Santa María, 1902 (VEI 6)

The Santa María eruption in 1902 was one of the biggest volcanic explosions of the 20th century. Prior to the dramatic eruption, the volcano in Guatemala had been quiescent for 500 years. The blast left a large crater, nearly a mile (1.5 km) across, on the mountain's southwest flank.

The symmetrical, tree-covered volcano is part of a chain of stratovolcanoes that rises along Guatemala's Pacific coastal plain. It has experienced continuous activity since its last blast, a VEI 3, which occurred in 1922.

Novarupta, 1912 (VEI 6)

The Novarupta eruption was the largest volcanic blast of the 20th century. The Novarupta volcano formed on the slope of the Trident Volcano complex. The volcano was part of a chain that dots the southern Alaska Peninsula and is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire. The powerful eruption sent 3 cubic miles (12.5 cubic kilometers) of magma and ash into the air, which fell to cover an area of 3,000 square miles (7,800 square km) in ash more than a foot deep, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

In Kodiak Alaska, nearly 100 miles (160 km) away, the air was so thick with ash that a lantern held at arm's length could barely be seen for 60 hours after the giant blast, according to the National Park Service. Pyroclastic flows after the eruption created the smoky, volcanically active region known as the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, which is peppered with fumaroles.

Mount Pinatubo, 1991 (VEI 6)

Mount Pinatubo is a stratovolcano in Luzon, Philippines. It is part of a volcanic arc created along a subduction zone where the Philippine and Eurasian plates meet. The cataclysmic eruption of Pinatubo was a classic explosive eruption. The eruption ejected more than 1 cubic mile (5 cubic kilometers) of material into the air and created a column of ash that rose up 22 miles (35 km) in the atmosphere. Ash fell across the countryside, even piling up so much that some roofs collapsed under the weight.

The blast also spewed millions of tons of sulfur dioxide and other particles into the air, which were spread around the world by air currents and caused global temperatures to drop by about 1 degree Fahrenheit (0.5 degree Celsius) over the course of the following year. Yet despite being a giant eruption in a heavily populated region, it wasn't as deadly as it might have been, thanks to good evacuation plans and round-the-clock monitoring.

Ambrym Island, A.D. 50 (VEI 6 +)

Nearly 2,000 years ago, the 257-square-mile (665-square-km) volcanic island of Ambrym, in what is now part of the tiny South Pacific Republic of Vanuatu, experienced one of the most impressive eruptions in history. It sent a wave of scalding ash and dust down the mountain and formed a caldera 7.5 miles (12 km) wide, according to the Smithsonian Institution.

Since that eruption, Ambrym's Marum caldera has continued to be one of the most active in the world. It has erupted close to 50 times since 1774, according to the USGS. In 1894, several people were killed by volcanic bombs and four people were overtaken by lava flows, and in 1979, acid rainfall caused by the volcano burned some inhabitants.

Ilopango Volcano, A.D. 431 (VEI 6 +)

Although this mountain in central El Salvador, just a few miles east of the capital city San Salvador, has experienced only two eruptions in its history, the first known eruption, in roughly A.D. 431, was a doozy. It blanketed much of central and western El Salvador with pumice and ash, and destroyed early Mayan cities, forcing inhabitants to flee, according to the Smithsonian Institution.

In a 2020 study in the journal PNAS , scientists precisely dated the eruption

and determined it produced about 0.9 F (0.5 C) of cooling for a few years. The blast likely contributed to the disruption of trade routes and the shift of the Mayan civilization from the highland areas of El Salvador to lowland areas to the north and in Guatemala.

The summit's caldera is now home to one of El Salvador's largest lakes.

Mount Thera, approx. 1610 B.C. (VEI 7)

Geologists think that the Greek island volcano Thera exploded with the energy of several hundred atomic bombs in a fraction of a second. Though it occurred during recorded history, there are no written descriptions of the eruption. Still, because the island was populated at the time, geologists think it could be the strongest explosion ever witnessed by modern humans.

Mount Thera's eruption was four or five times more massive than Krakatoa and blew massive hole in Santorini, the island in the Aegean Sea that hosted the volcano. At the time, the Minoan civilization flourished on the island. Some evidence suggests that the inhabitants of the island suspected the volcano was going to blow its top and evacuated. But though those residents might have escaped, some archaeologists believe the volcano severely disrupted the culture, with tsunamis and temperature declines caused by the massive amounts of sulfur dioxide it spewed into the atmosphere that altered the climate.

Changbaishan Volcano, A.D. 1000 (VEI 7)

Changbaishan, also known as Baitoushan Volcano, straddles the border of China and North Korea. A massive eruption a millennium ago spewed volcanic material as far away as northern Japan, a distance of approximately 750 miles (1,200 kilometers). The eruption also created a large caldera nearly 3 miles (4.5 km) across and a half-mile (0.8 km) deep at the mountain's summit. It is now filled with the waters of Lake Tianchi, or Sky Lake, which is shared by both China and North Korea. The picturesque body of water is now a popular tourist destination both for its natural beauty and alleged sightings of unidentified creatures living in its depths.

The volcano last erupted in 1702, and geologists consider it to be dormant. Gas emissions were reported from the summit and nearby hot springs in 1994, but no evidence of renewed activity of the volcano was observed.

Mount Tambora, 1815 (VEI 7)

The explosion of Mount Tambora is the largest ever recorded by humans, ranking a 7 (or "super-colossal") on the VEI, the second-highest rating in the index. The volcano, which is still active, is one of the tallest peaks in the Indonesian archipelago.

The eruption reached its peak in April 1815, when it exploded so loudly that it was heard on Sumatra Island, more than 1,200 miles (1,930 km) away. The death toll from the eruption was estimated at more than 11,000 due to direct exposure to pyroclastic flows. However, the eruption unleashed food shortages that lasted over the next decade, ultimately killing 100,000 people, according to the NOAA.

Yellowstone eruption, 640,000 years ago (VEI 8)

The entire Yellowstone National Park is an active volcano rumbling beneath visitors' feet. And though it hasn't erupted dramatically in recorded history, it does have an incredibly violent past: Three magnitude-8 eruptions rocked the area as far back as 2.1 million years ago, again 1.2 million years ago and most recently 640,000 years ago. "Together, the three catastrophic eruptions expelled enough ash and lava to fill the Grand Canyon," according to the USGS. In fact, scientists discovered a humongous blob of magma stored beneath Yellowstone, a blob that if released could fill the Grand Canyon 11 times over.

The latest of the trio of supervolcano eruptions created the park's huge crater, measuring 30 by 45 miles across (48 by 72 km).

Yellowstone is probably The chance of such a supervolcano eruption happening today is about 1 in 700,000 every year, Robert Smith, a seismologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, previously told Live Science.

So are we overdue for an eruption from this supervolcano? Not really. Though Yellowstone last erupted around 70,000 years ago, magma conditions don't indicate this monster is likely to blow anytime soon.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.