Big blob of hot water in Pacific may be making El Niño act weirdly

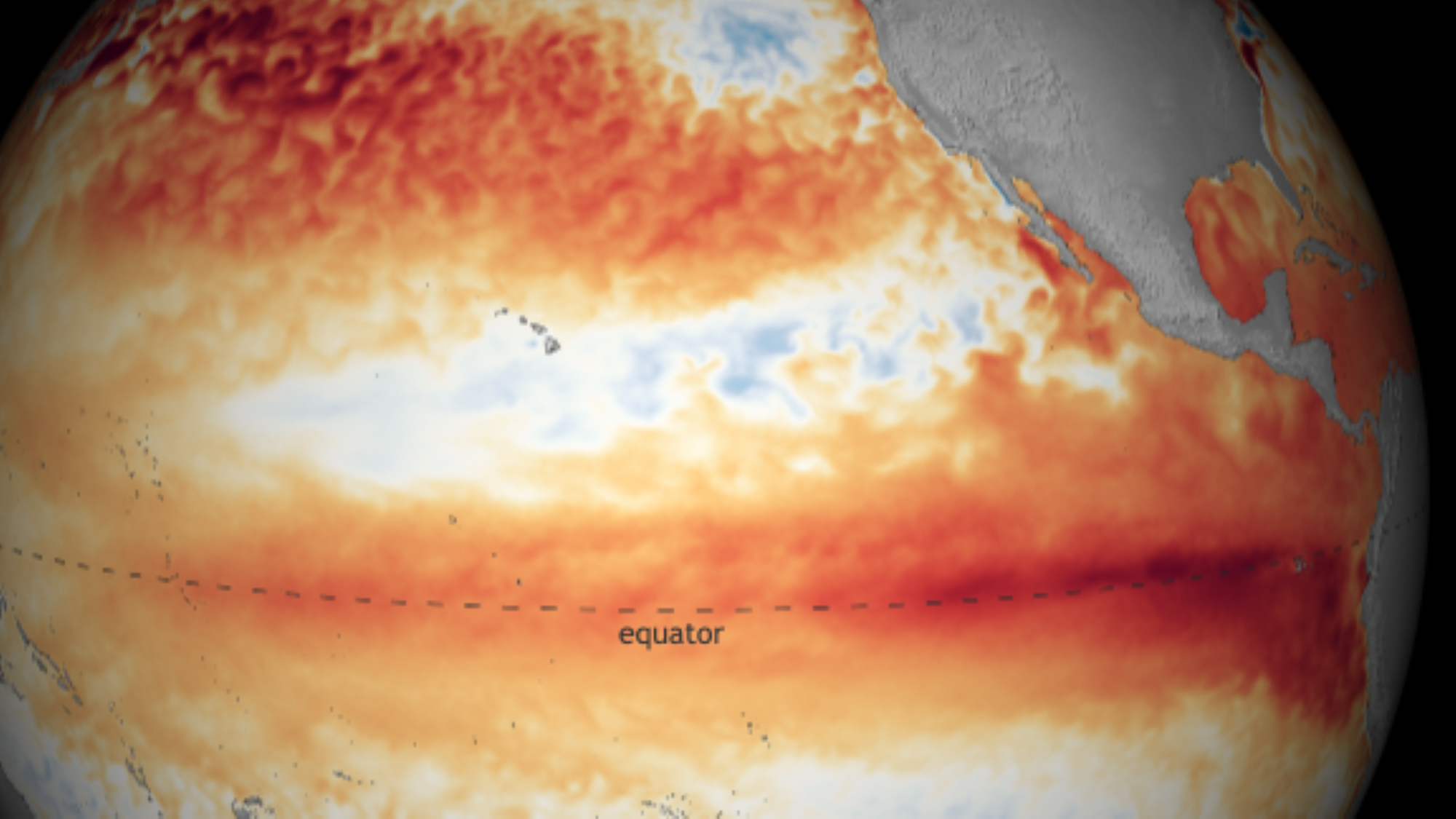

El Niño is in full swing and will likely remain "strong" this winter, but its effect on weather patterns in the U.S. depends on the behavior of an unusually warm blob in the western Pacific, experts say.

A weird blob of warm water that has appeared in the western Pacific seems to be making this year's "strong" El Niño behave unexpectedly, reports The Washington Post.

The blob is located in the west-central Pacific, near the International Dateline — a north-south boundary that separates two consecutive calendar dates — Paul Roundy, a professor of atmospheric science at the University of Albany, told the newspaper.

El Niño usually triggers warming in the eastern tropical Pacific, which in turn shapes atmospheric conditions and weather patterns across North America and around the world. While this year's El Niño event comes as no surprise — experts warned it could be a big one in May — the atmospheric response "looks nothing like other recent strong El Niño events," Todd Crawford, a meteorologist at the weather forecasting consultancy Atmospheric G2, wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter, on Nov. 8.

During typical El Niño years, warm waters in the eastern tropical Pacific heat the air above and cause it to rise. But that isn't happening now, experts told the Washington Post, because air is rising in the western Pacific instead. Some of this air may be blowing east and suppressing the rising motion usually seen there, they said.

Related: A strong El Niño is coming this winter. What does that mean?

Rising air creates low pressure conditions associated with showers and thunderstorms. The warm blob in the western Pacific is causing "more tropical rain to fall there, which in turn reduces the intensity of the rainfall farther east because the air that rises in the west Pacific thunderstorms subsides back toward the surface farther east, drying the atmosphere," Roundy said.

El Niño may be behaving abnormally this year because of lingering effects from a rare "triple dip" of La Niña events — El Niño's chilly counterpart. La Niña produced a sustained cooling effect around the equator and eastern tropical Pacific over the past three years and probably "hasn't completely washed out," Crawford told the Washington Post. High ocean temperatures resulting from human-caused climate change may also be to blame for the unusual warmth in the western Pacific, according to the newspaper.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As we've discussed extensively in our recent client reports and Webinars, while ocean temperatures are suggestive of a strong El Nino event, the atmospheric response in the central/eastern tropical Pacific looks nothing like other recent strong El Nino events. Here, you can see… pic.twitter.com/grq94a1BD8November 8, 2023

Strong El Niño conditions could persist through the Northern Hemisphere winter and last until spring 2024, the National Weather Service said in its latest advisory, with a 35% chance the event could become "historically strong" from November to January. "Strong El Niño events increase the likelihood of El Niño-related climate anomalies but do not necessarily equate to strong impacts," representatives wrote in the advisory on Nov. 9.

El Niño winters typically see masses of warm air building across Alaska, western Canada and the northern U.S., the Washington Post reported. Cooler, wetter conditions usually predominate in the southern states.

Similar conditions may still arise this winter, despite the warm blob's appearance, Roundy said. "This interference of west Pacific warmth appears to be declining," he said, adding that a body of warm water forming to the east of the International Dateline may trigger heavier rainfall there.

A burst of westerly winds could also push warm water sitting on the blob's surface toward the eastern Pacific, Roundy noted. This would expose cooler layers of water underneath and "encourage more normal strong El Niño signals to emerge this winter," he said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.