Bizarre polar vortex over Antarctica delayed ozone hole opening, scientists say

The Antarctic ozone hole usually starts forming in early August, but rare warming events and a strangely elongated polar vortex this year may have delayed its arrival.

Sudden and rare warming events in Antarctica may have delayed the arrival of the ozone hole that appears above the frozen continent every year, scientists say.

These warming events likely impacted a swirl of winds known as the southern polar vortex, which in turn affected the ozone hole's formation, the researchers say.

Ozone is a gas that forms a layer in the stratosphere — the middle section of the atmosphere that extends between 12 and 31 miles (20 to 50 kilometers) above Earth's surface — and shields life from harmful ultraviolet solar radiation. The Antarctic ozone hole opens in this protective layer every year during the Southern Hemisphere's spring, which lasts from September to November. Records going back to 1979 indicate that the ozone layer above the South Pole usually starts to disintegrate at the beginning of August, but this year's event appears to have been delayed.

"Instead of the typical behavior, deepening progressively during August, the ozone hole didn't develop until the end of the month," researchers with the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, a European Union body that provides daily analyses and forecasts regarding Earth's atmosphere, wrote in a statement.

The delay is due to two warming episodes that deformed the southern polar vortex earlier this year, according to the statement. On separate occasions in July and August, temperatures in the stratosphere above Antarctica increased by 27 and 31 degrees Fahrenheit (15 and 17 degrees Celsius), respectively. Such warming events are rare over the South Pole, the researchers noted, but they're more common over the North Pole.

Related: 'We were in disbelief': Antarctica is behaving in a way we've never seen before. Can it recover?

It's unclear what caused the two warming events, but NASA scientists noted highly unusual weather in the troposphere (the layer of the atmosphere directly above Earth) over Antarctica in July, with temperatures reaching record-high levels. Variations in sea surface temperatures and sea ice can propagate up into the stratosphere, "but the attribution of why these systems develop is really difficult to do," Paul Newman, an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a separate statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Specific conditions are needed for the ozone hole to form, including a strong polar vortex, solar radiation and ozone-depleting substances (ODS).

A strong polar vortex is characterized by powerful, circular winds and extremely cold temperatures — conditions that caused a hole bigger than North America to open over Antarctica last year.

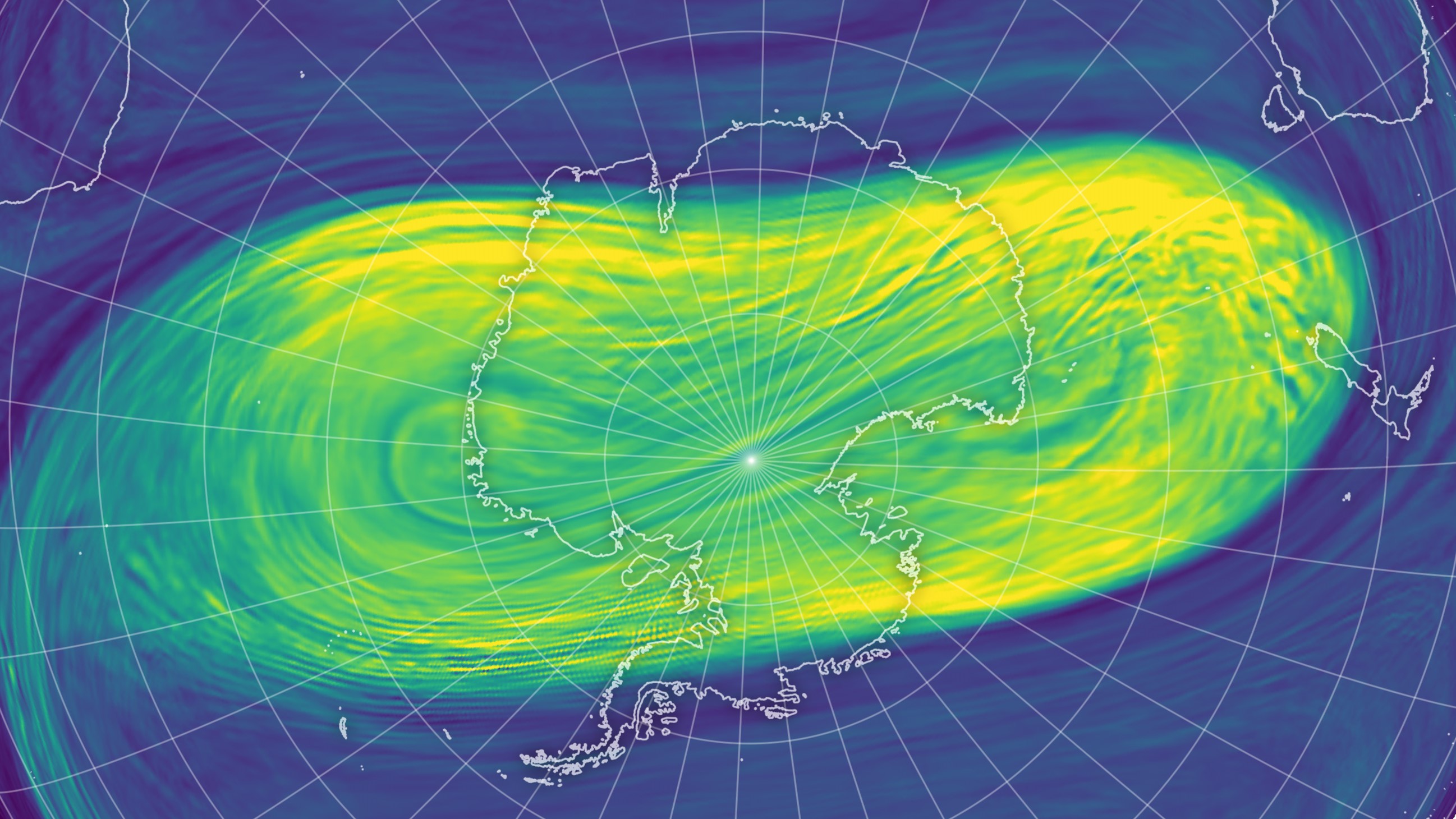

However, instead of being strong and circular, this year's southern polar vortex was weak and elongated, according to the statement. This delayed ozone depletion in the stratosphere, even as sunlight returned in August after the South Pole's polar night.

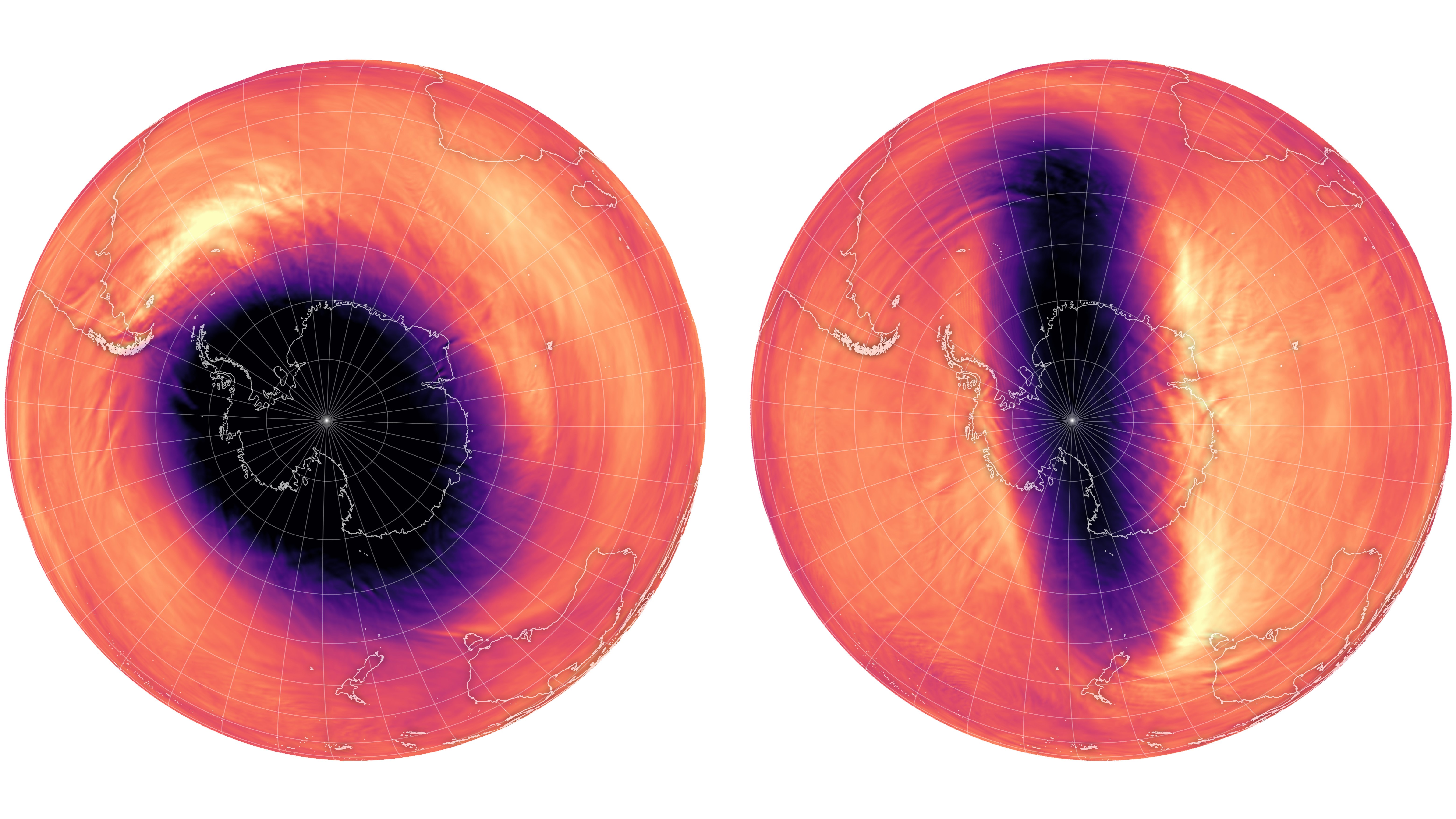

Ozone depletion usually begins in a belt around the edge of the vortex, and then works its way inward to form a hole through austral spring. The hole disappears as temperatures warm progressively during the Southern Hemisphere summer, usually in December.

The Antarctic ozone hole originally formed due to humans pumping ozone-depleting chemicals into the atmosphere. International agreements now ban these chemicals, including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) that were used in air conditioners and refrigerators.

Evidence suggests the ozone layer is healing, but "a slow start of an ozone hole can't automatically be attributed to a recovery of the ozone layer," the researchers wrote in the statement. "The health of the stratospheric ozone layer depends on a complex combination of chemical and meteorological factors."

If countries continue to respect the ban on ODS, the hole should theoretically recover within about four decades, the researchers noted. "In the meantime, the size and behavior of the ozone hole will be influenced by meteorological variability, anthropogenic and natural ODS sources and the impacts of climate change," they added. Natural causes of ozone depletion include volcanic eruptions, such as Tonga's 2022 record-shattering eruption.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.