Scientists drilled into Belize's Great Blue Hole and discovered a worrying trend

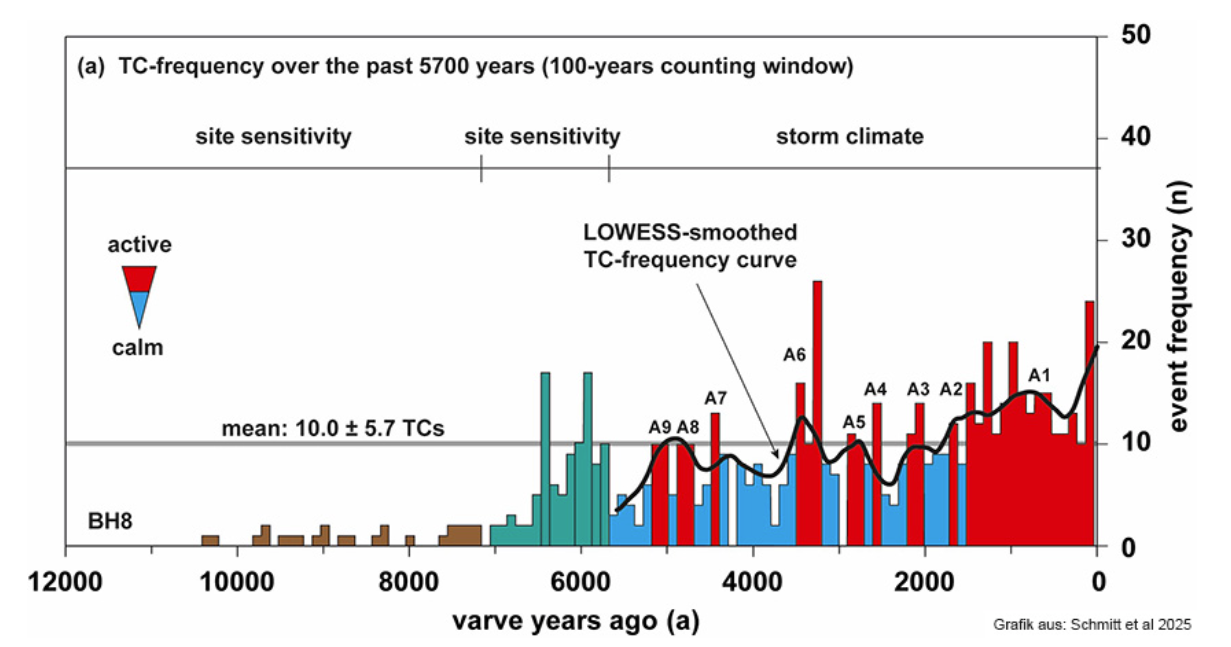

Tropical storms have been steadily increasing in frequency over the past 5,700 years, new evidence from sediment in the Great Blue Hole reveals, with a massive spike in the past two decades.

Tropical cyclones in the Caribbean are getting more frequent — and could increase significantly in the coming decades, evidence found buried deep within the Great Blue Hole suggests.

Researchers took a sediment core from the Great Blue Hole sinkhole, situated about 50 miles (80 kilometers) off the coast of Belize, which revealed that tropical cyclones have increased in frequency over the past 5,700 years. The scientists described their findings in a study published March 14 in the journal Geology.

"A key finding of our study is that the regional storm frequency has increased continuously since 5,700 years B.P. (before present)," study lead author Dominik Schmitt, a researcher at Goethe University Frankfurt's Biosedimentology Research Group, told Live Science. "Remarkably, the frequency of storm landfalls in the study area has been much higher in the last two decades than in the last six millennia — a clear indication of the influence of Modern Global Warming."

The bottom of the Great Blue Hole

Tropical cyclones are intense, rotating, low-pressure systems that form over warm ocean waters. They transfer heat from the ocean into the upper atmosphere. Tropical cyclones can be extremely destructive, producing strong winds, heavy rainfall and storm surges.

To learn more about these storms over a long period of time, the researchers extracted the sediment core from the bottom of the 410-foot-deep (125 meters) Great Blue Hole — a massive underwater sinkhole that formed as sea levels rose during the last ice age, around 10,000 years ago. This sediment core, measuring 98 feet (30 m) long, is the longest continuous record of tropical storms in the area.

By analyzing the layers of sediment in the core, the scientists could determine the number of tropical cyclones that had occurred over the past 5,700 years. Two layers of fair-weather sediment are usually laid down every year, enabling the researchers to count back the years like the rings of a tree and compare when storm-event sediment layers were deposited.

The researchers found that tropical cyclones have been getting more frequent over the past 5,700 years, with a particular increase in frequency since we started burning fossil fuels during the Industrial Revolution.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Over the past six millennia, between four and sixteen tropical storms and hurricanes have passed over the Great Blue Hole every century," Schmitt said. In the past 20 years alone, however, the researchers found evidence of nine tropical storms passing over the same region.

There appear to be two factors driving the rise in tropical cyclones, the researchers noted. Much of the frequency increases over the past few thousand years may be due to a southward migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).

The ITCZ is a region near the equator where the trade winds of the Northern and Southern hemispheres come together, resulting in low atmospheric pressure, high humidity and frequent thunderstorms. Along the northern edge of the ITCZ is the Hurricane Main Development Region (MDR), where most tropical cyclones in the Atlantic form.

The ITCZ usually moves northward in the summer and southward in the winter as a result of changing sea surface temperatures, but it has also been steadily moving southward over the past few thousand years.

This southward migration of the ITCZ "has probably led to a southward displacement of the major Atlantic storm genesis region, and a shift of the main storm trajectories from formerly higher to now lower latitudes," Schmitt explained.

A surge in storms

Increases in global sea surface temperatures as a result of human-caused climate change are likely responsible for the recent spike in tropical storms, and will likely result in even more frequent tropical cyclones in the coming decades, according to the study.

"The nine modern storm layers from the last 20 years indicate that extreme weather events in this region will become much more frequent in the 21st century," Schmitt said.

The researchers predict that as many as 45 tropical storms and hurricanes could hit the Caribbean before the end of 2100.

"This high number is far in excess of what has been the case in the past 5,700 years," Schmitt said. "An explanation for this high storm frequency is not the natural variations in climate or solar radiation, but the progressive global warming during the Industrial Age, accompanied by fast rising sea-surface temperatures and stronger global La Niña events, which create optimal conditions for the development and rapid intensification of storms."

Jess Thomson is a freelance journalist. She previously worked as a science reporter for Newsweek, and has also written for publications including VICE, The Guardian, The Cut, and Inverse. Jess holds a Biological Sciences degree from the University of Oxford, where she specialised in animal behavior and ecology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.