Why isn't the darkest time of the year also the coldest?

Why aren't the solstices the coldest and hottest days of the year?

The darkest time of the year is the winter solstice, the day with the least sunlight and the longest night. However, the coldest time of the year is typically about one month after the winter solstice. So why isn't the darkest time of the year also the coldest?

The answer has to do with Earth's tilt and how our planet retains heat.

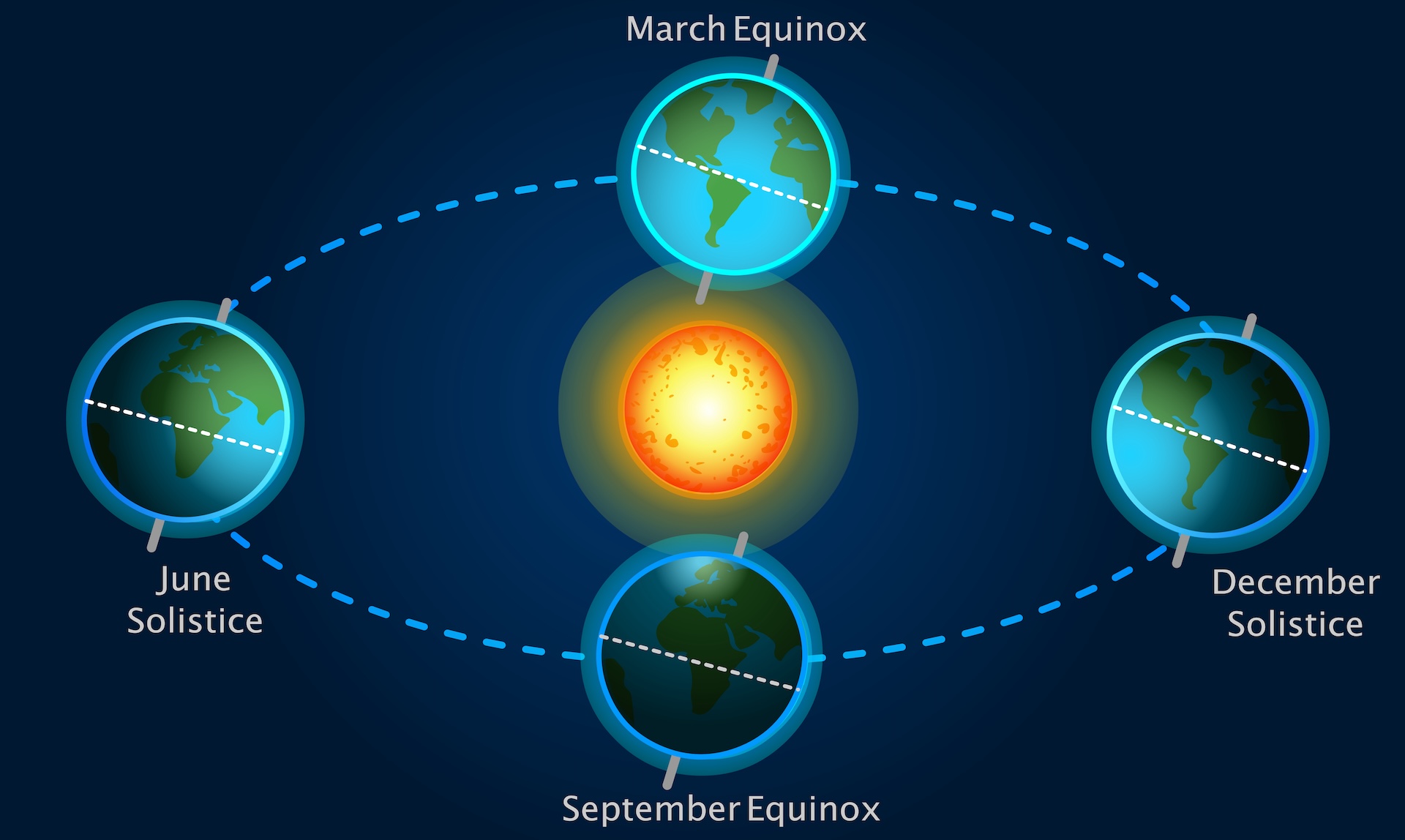

Earth's axis — the imaginary line connecting the North and South poles — is tilted at about a 23.4-degree angle from the path the planet takes around the sun. This means that one day every year on Earth, the North Pole points to its greatest extent away from the sun. On another day, it's the South Pole that aims as far from the sun as possible. These days are the northern and southern winter solstices, respectively, explained Christopher Baird, an associate professor of physics at West Texas A&M University.

The more Earth's surface is tilted away from the sun, the less time it spends in daylight. The northern winter solstice, the shortest day in the Northern Hemisphere, occurs on Dec. 21, 22 or 23 each year, and the southern winter solstice happens annually on June 20, 21 or 22.

Earth gets most of its warmth from the sun, which might lead you to guess that the winter solstices are the coldest days of the year in their respective hemispheres, Baird noted. However, the coldest temperatures in each hemisphere "tend to be offset by roughly one month from these solstices," Nick Bassill, director of the State Weather Risk Communications Center at the University at Albany in New York, told Live Science. In the Northern Hemisphere, this is about the middle of January.

Related: Which is colder: The North or South Pole?

The reverse holds true as well. The summer solstice, the longest day of the year — which occurs on June 20, 21 or 22 in the Northern Hemisphere and Dec. 21, 22 or 23 in the Southern Hemisphere — is often not the warmest day of the year, Jason Steffen, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, "the Mojave is hottest at the end of July, long after the solstice," Steffen said. "The Gulf Coast of Florida is hottest in August."

This delay between the solstices and the coldest or warmest temperatures of the year, an effect called "seasonal lag," "is because physical objects — the lakes and oceans, the ground, concrete, and so on — don't immediately respond to warmer or colder temperatures," Bassill explained. "In the winter, this means that physical objects hold on to their warmth from fall and summer longer than the air does."

The closer a location is to the ocean, the greater these seasonal variations in temperature are muted, because "it takes four times as much energy to raise the temperature of water by one degree as it does rock," Steffen said. In addition, "the oceans circulate," he added. This means that even when nights are long, heat flowing in the ocean can help keep those locations warm.

"For areas immediately downwind of a large water body, such as places on the Pacific Coast of the U.S., their coldest temperatures in winter tend to be warmer than other places at a similar latitude due to this effect," Bassill said. "It can also mean that their seasonal lag might be larger than other locations, meaning the time difference between their solstice and coldest or warmest time of year can be greater than other places in the world that are further away from a large water body."