Dry conditions across Southern California set the stage for a series of deadly wind-driven wildfires that burned thousands of homes and other structures in the Los Angeles area in early January 2025.

Ming Pan, a hydrologist at the University of California-San Diego's Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes, tracks the state's water supplies. He put Southern California's dryness into perspective using charts and maps.

How dry is Southern California right now?

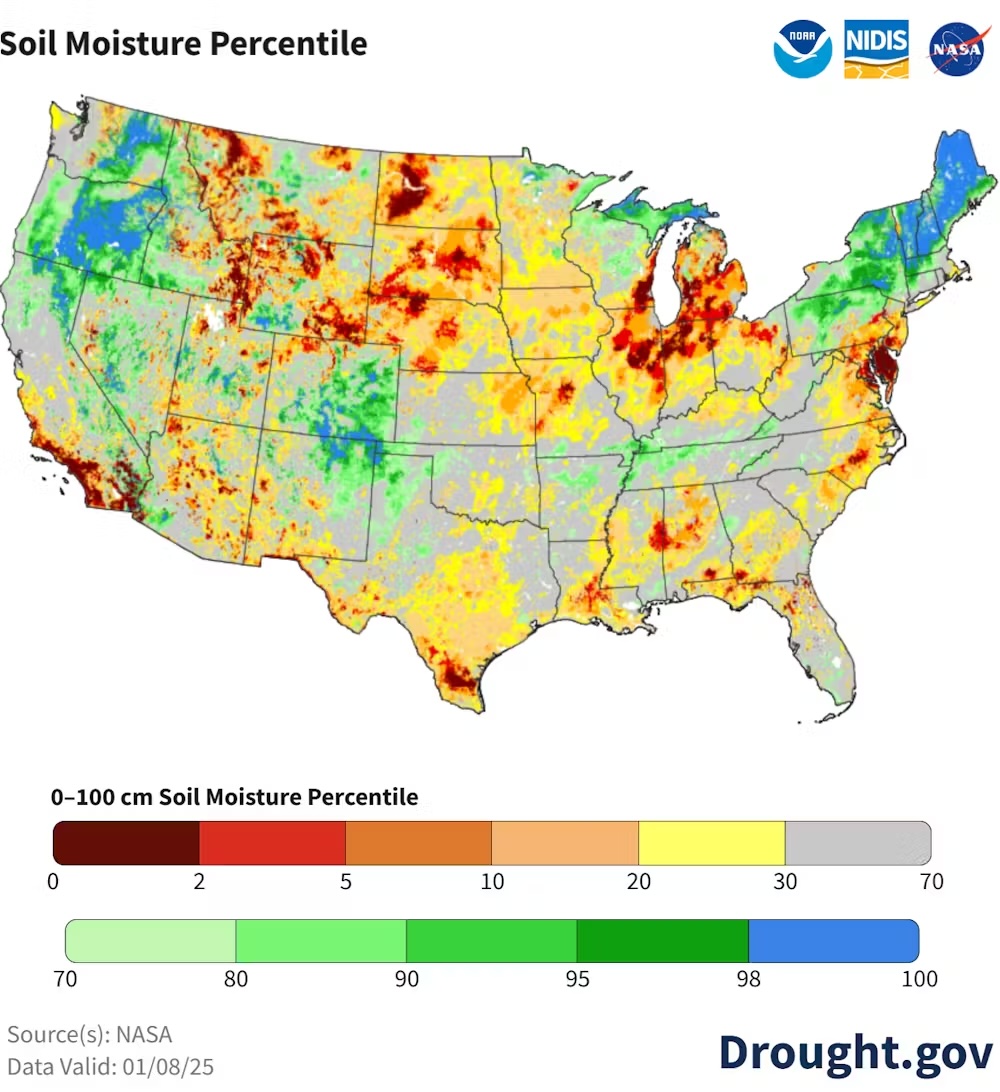

In early January, the soil moisture in much of Southern California was in the bottom 2% of historical records for that day in the region. That's extremely low.

Hydrologists in California watch the sky very closely starting in October, when California's water year begins.

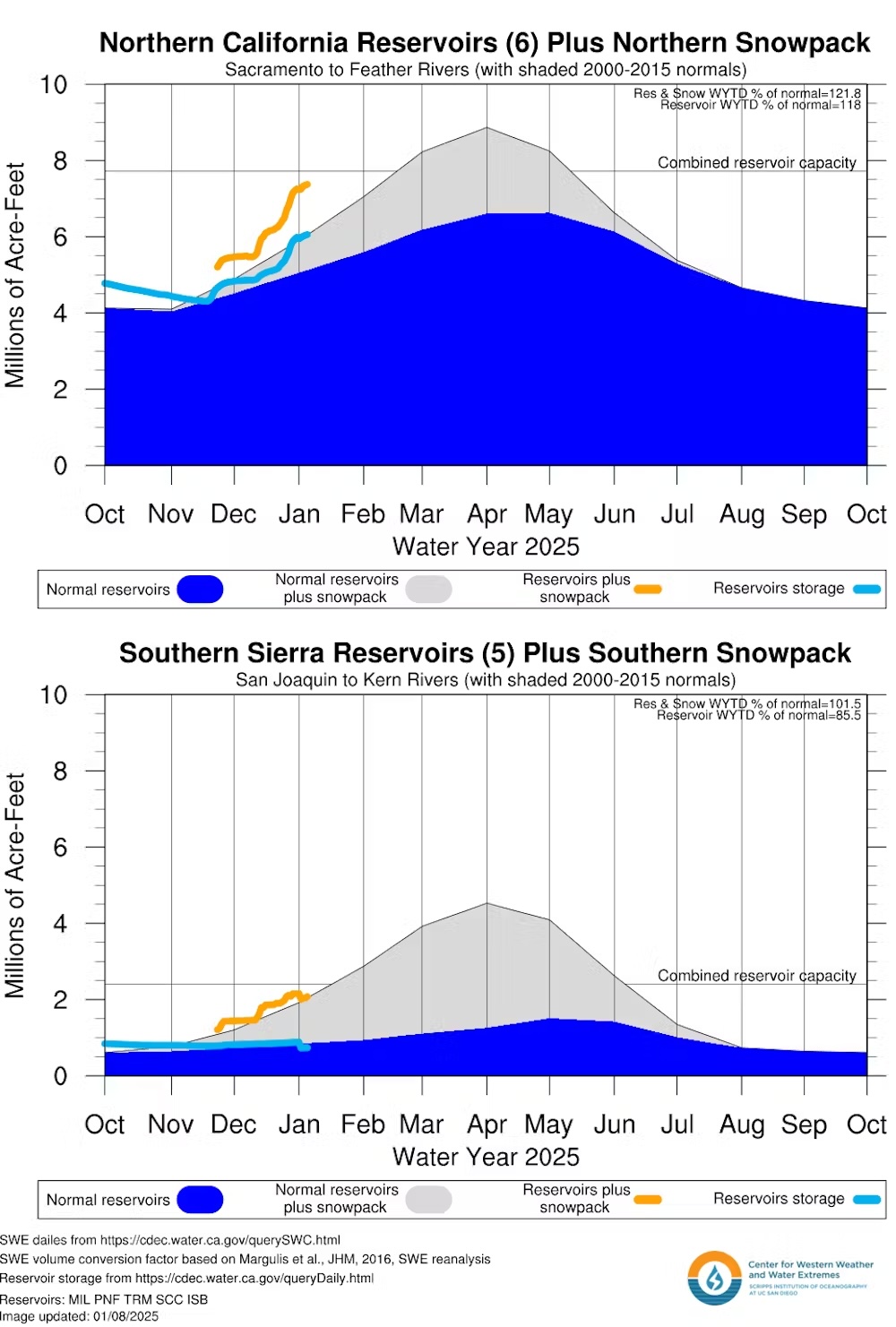

The state gets very little rain from May through September, so late fall and winter are crucial to fill reservoirs and to build up the snowpack to provide water. California relies on the Sierra snowpack for about one-third of its freshwater supply.

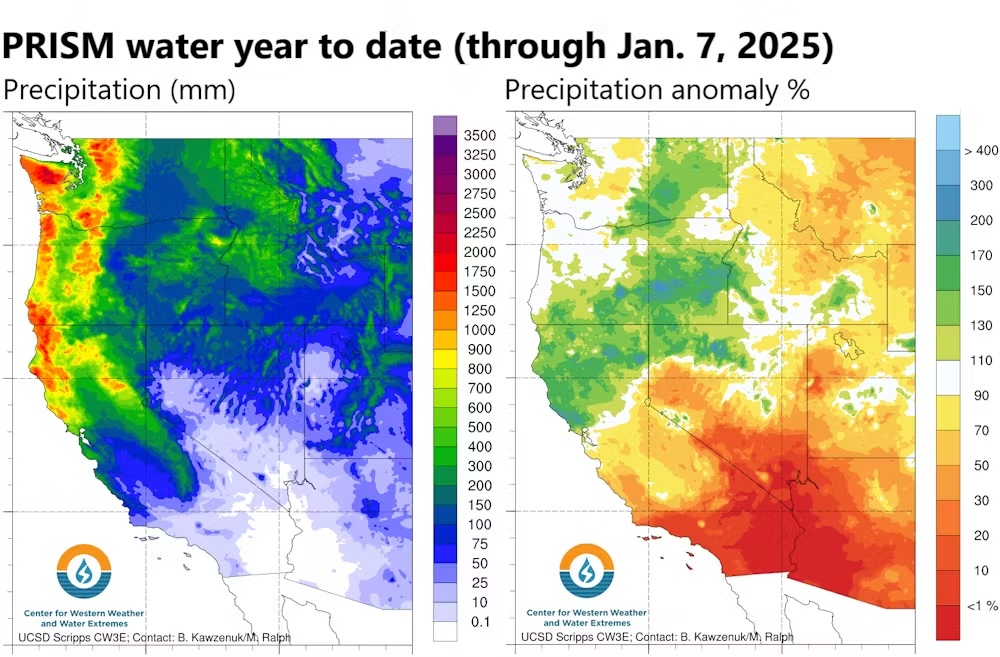

However, Southern California started out the 2024-25 water year pretty dry. The region got some rain from an atmospheric river in November, but not much. After that, most of the atmospheric rivers that hit the West Coast from October into January veered northward into Washington, Oregon and Northern California instead.

When the air is warm and dry, transpiration and evaporation also suck water out of the plants and soil. That leaves dry vegetation that can provide fuel for flying embers to spread wildfires, as the Los Angeles area saw in early January.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: Santa Ana winds: What is causing the deadly fires sweeping across Los Angeles?

So, while Northern California's water and snowpack conditions are in good shape, Southern California is much drier and its water storage is not doing so well.

The Southern Sierra snowpack was starting to dip below normal in early January.

What can California expect for the rest of 2025?

The U.S. Climate Prediction Center's seasonal outlook through March suggests that drought is likely to develop in the region in the coming months.

The outlook takes into account forecasts for La Niña, an ocean temperature pattern that was on its way to developing in the Pacific Ocean in early 2025. La Niña tends to mean drier conditions in Southern California. However, not every La Niña affects California in the same way.

One or two big rain events could completely turn the table for Southern California's water situation. In 2023, California saw atmospheric rivers in April.

So, it's hard to say this early in the season how dry Southern California will be in the coming months, but it's clear that people in dry areas need to pay attention to the risks.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dr. Ming Pan joined CW3E as a senior research hydrologist in 2021. He previously served as a associate research scientist at Princeton University. His research focuses on quantifying various states of the terrestrial water cycle at different scales from local to global, and developing the data and tools for solving related application problems.