Top-secret Cold War military project found perfectly preserved fossil plants under Greenland ice

Frozen soil held plant fragments that may be a million years old.

Frozen soil that was collected in Greenland during the Cold War by a secret military operation hid another secret: buried fossils that could be a million years old. Recent analysis revealed plants that were so well-preserved they "look like they died yesterday," researchers said.

U.S. Army scientists dug up the ice core in northwestern Greenland in 1966 as part of Project Iceworm, a covert mission to build a subsurface base concealing hundreds of nuclear warheads, where they would be within striking range of the Soviet Union. An Arctic research station named Camp Century was the Army's cover story for the project. But Iceworm fizzled; the base was abandoned and the ice core lay forgotten in a freezer in Denmark until it was rediscovered in 2017.

When scientists investigated the core in 2019 they discovered fragments of fossilized plants that may have bloomed a million years ago. Greenland's present ice cover was thought to be nearly 3 million years old, but the tiny plant fragments say otherwise, showing that at some point within the last million years — possibly within the last few hundred thousand years — much of Greenland was ice-free.

Related: Images of melt: Earth's vanishing ice

Today, most of Greenland is covered by the Greenland Ice Sheet, which spans 656,000 square miles (1.7 million square kilometers) — about three times the size of Texas, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

If the new research bears out and most of Greenland's ice vanished relatively recently, that doesn't bode well for the stability of its current ice sheet in response to human-caused climate change. Should all of Greenland's ice melt, the seas would rise by approximately 24 feet (7 meters), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported in 2019. That would be enough to flood coastal cities worldwide, the researchers wrote in the new study, published March. 15 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Cold War science

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began constructing Camp Century in 1959, and scientists B.L. Hansen and Chester Langway Jr. supervised extraction of an ice core measuring 11 feet (3.4 meters) from a depth of 4,488 feet (1,368 m) below the ice. After the Army terminated Project Iceworm, the core went into storage, first at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where Langway was a researcher, and then at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, said Andrew Christ, lead author of the new study and a postdoctoral fellow and lecturer in the Department of Geology at The University of Vermont in Burlington.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The bottom of the ice core is these frozen chunks of sediment, about 10 centimeters [4 inches] long and 10 centimeters across," Christ told Live Science. "They put them in glass cookie jars and labeled them 'Camp Century sub ice' — and then forgot about them." It wasn't until 2017, during an inventory of materials bound for a new freezer, when facility curator Jørgen Peder Steffensen recognized the long-lost core samples. He promptly contacted researchers about examining the sediments for the first time since the 1960s, Christ said.

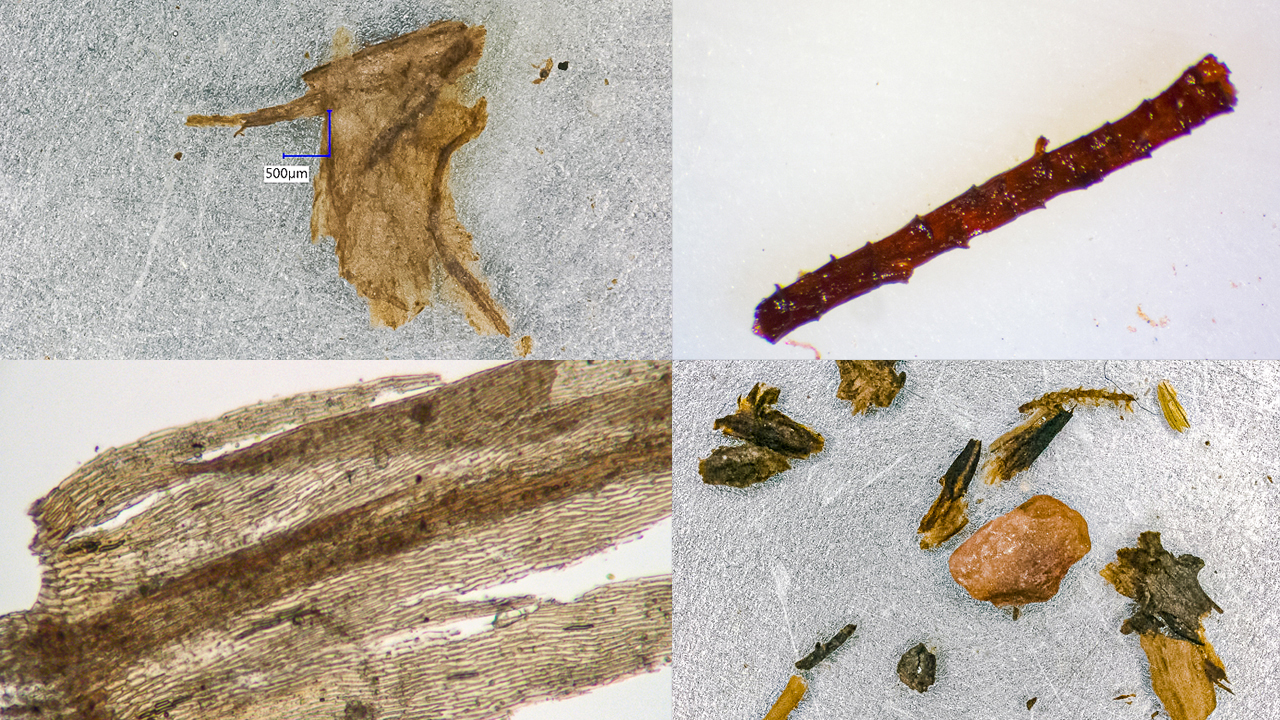

"When we found the fossils, it was one of those science 'Eureka!' moments, it was totally unexpected," Christ told Live Science. As they rinsed the frozen soil to sort it into different-size grains, they noticed "little black things" floating in the water. Christ put some of the floating specks under a microscope, "and boom! There were fossil twigs and leaves in this frozen sediment," Christ said. "The best way to describe them is freeze-dried. When we pulled these out and put a little water on them, they kind of unfurled, so they looked like they died yesterday."

Such plants — possibly from a boreal forest — could grow on Greenland only if the island's ice sheet were mostly gone, so the next step was figuring out how recently that happened, the study authors wrote.

Buried climate clues

To date the plants, the scientists looked at isotopes (variants of the same element with a different number of neutrons) of aluminum and beryllium, which accumulate in minerals when exposed to radiation that filters through the atmosphere. These isotopes can tell scientists how long minerals were exposed at the surface, and how long they were buried underground.

Based on isotope ratios, the study authors determined that the soil — and the plants that grew in it — last saw sunlight between a few hundred thousand and about a million years ago, the researchers reported. Traces of leaf waxes in the core sediments resembled those of present-day tundra ecosystems in Greenland, according to the study.

The environmental isotope oxygen-18, found in ice locked in sediment pores in the core, offered further clues about this ancient ecosystem. Oxygen-18 in the core sediments was 6% to 8% higher than the average during the latter part of the Holocene epoch; one explanation is that it came from precipitation permeating soil at lower elevations, because widespread ice cover was scarce.

"We definitely had an ice-free northwest Greenland in that span of time," Christ said.

Based on geologic records and ocean geochemistry, scientists estimated Greenland's present ice sheet persisted at more or less the same size for about 2.6 million years, the study authors wrote. However, their new findings show that ice vanished almost entirely from Greenland during at least one period in the island's most recent deep freeze, presenting a previously unknown threshold for ice sheet stability.

In fact, scientists are already warning that Greenland is accelerating toward a critical tipping point of ice loss, with winter snowfall predicted to cease replenishing seasonal melt by as soon as 2055, Live Science reported in February.

"This is important as we move forward into a warmer future," Christ said. "Our climate system has a delicate balance to it. If it changes enough, you can melt away large portions of these ice sheets and raise sea levels — and that would inundate and flood large portions of the most densely populated areas on Earth."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.