Hidden tide in Earth's magnetospheric 'plasma ocean' revealed in new study

Researchers have detected fluctuations in Earth's magnetosphere created by the same tidal forces that the moon exerts on the oceans.

The moon exerts a previously unknown tidal force on the "plasma ocean" surrounding Earth's upper atmosphere, creating fluctuations that are similar to the tides in the oceans, a new study suggests.

In the study, published Jan. 26 in the journal Nature Physics, scientists used more than 40 years of data collected by satellites to track the minute changes in the shape of the plasmasphere, the inner region of Earth's magnetosphere, which shields our planet from solar storms and other types of high-energy particles.

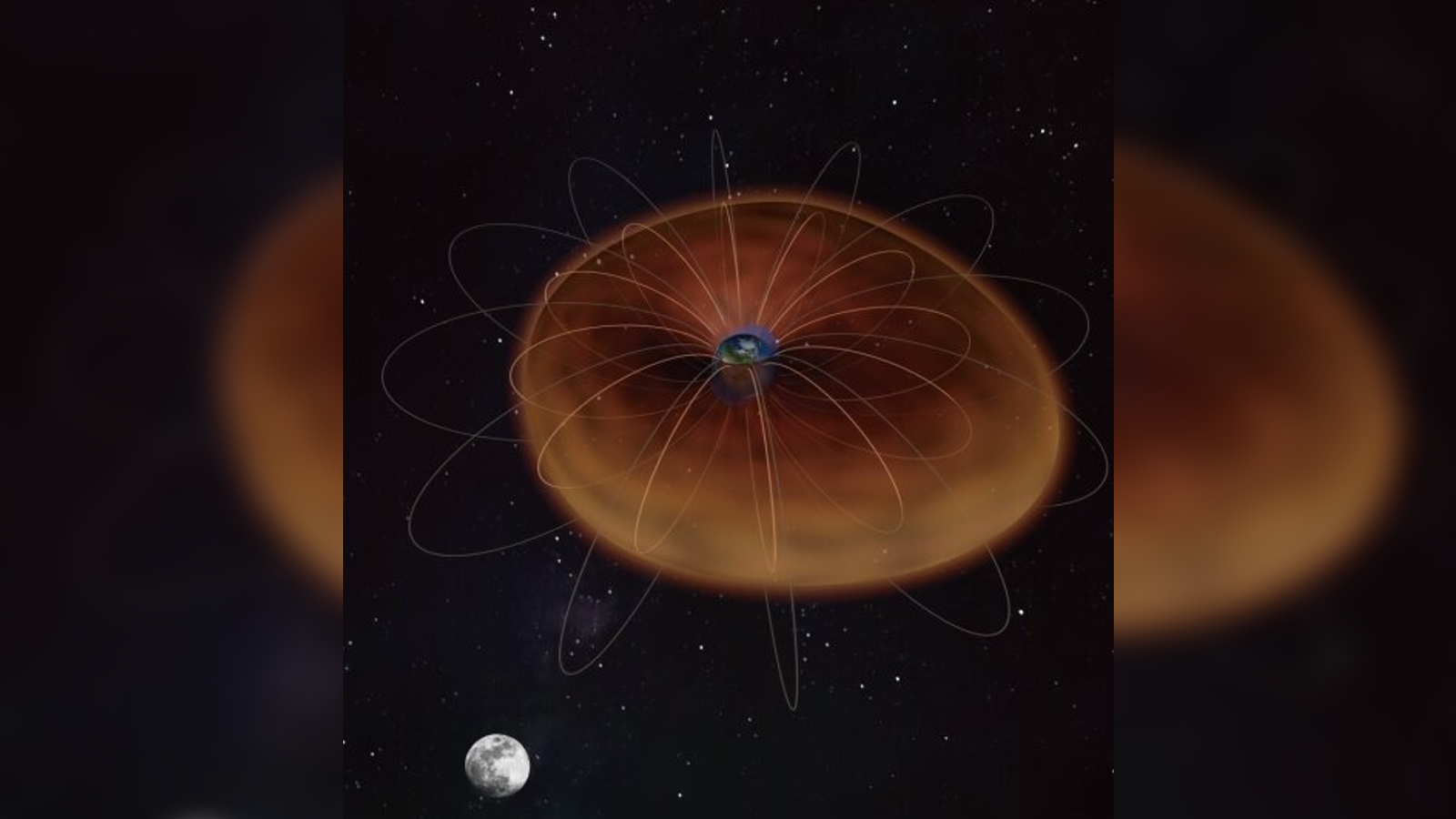

The plasmasphere is a roughly doughnut-shaped blob of cool plasma that sits on top of Earth's magnetic field lines, just above the ionosphere, the electrically charged part of the upper atmosphere. The plasma, or ionized gas, in the plasmasphere is denser than the plasma in the outer regions of the magnetosphere, which causes it to sink to the bottom of the magnetosphere. The boundary between this dense sunken plasma and the rest of the magnetosphere is known as the plasmapause.

"Given its cold, dense plasma properties, the plasmasphere can be regarded as a 'plasma ocean,' and the plasmapause represents the 'surface' of this ocean," the researchers wrote in the paper. The moon's gravitational pull can distort this "ocean," causing its surface to rise and fall like the ocean tides.

Related: Colossal asteroid impact forever changed the balance of the moon

The moon is already known to exert tidal forces on Earth's oceans, crust, near-ground geomagnetic field and the gas within the lower atmosphere. However, until now, nobody had tested to see if there was a tidal effect on the plasmasphere.

To investigate this question, the researchers analyzed data from more than 50,000 crossings of the plasmasphere by satellites belonging to 10 scientific missions, including NASA's Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS) mission. The satellites' sensors are capable of detecting minute changes in the concentrations of plasma, which allowed the team to map out the exact boundary of the plasmapause in greater detail than ever before.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The satellite crossings occurred between 1977 and 2015, and during this period, there were four complete solar cycles. This information allowed the team to factor in the role of solar activity on Earth's magnetosphere. Once the sun's influence was accounted for, it started to become clear that fluctuations in the shape of the plasmapause followed daily and monthly patterns that were very similar to the ocean's tides, indicating that the moon was the most likely cause of the plasma tides.

The researchers are unsure exactly how the moon causes the plasma tides, but their current best guess is that the moon's gravity causes perturbations in Earth's electromagnetic field. But further research is needed to tell for sure.

Related: How did the moon form? A supercomputer may have just found the answer

The team thinks this previously unknown interaction between Earth and the moon could help researchers understand other parts of the magnetosphere in greater detail, such as the Van Allen radiation belts, which capture highly energetic particles from solar wind and trap them in the outer magnetosphere.

"We suspect that the observed plasma tide may subtly affect the distribution of energetic radiation belt particles, which are a well-known hazard to space-based infrastructure and human activities in space," the researchers wrote. Better understanding the tides could therefore help to improve work in these areas, they added.

The researchers also want to see if plasma in the magnetospheres of other planets is influenced by those planets' moons. "These findings may have implications for tidal interactions in other two-body celestial systems," they wrote.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.