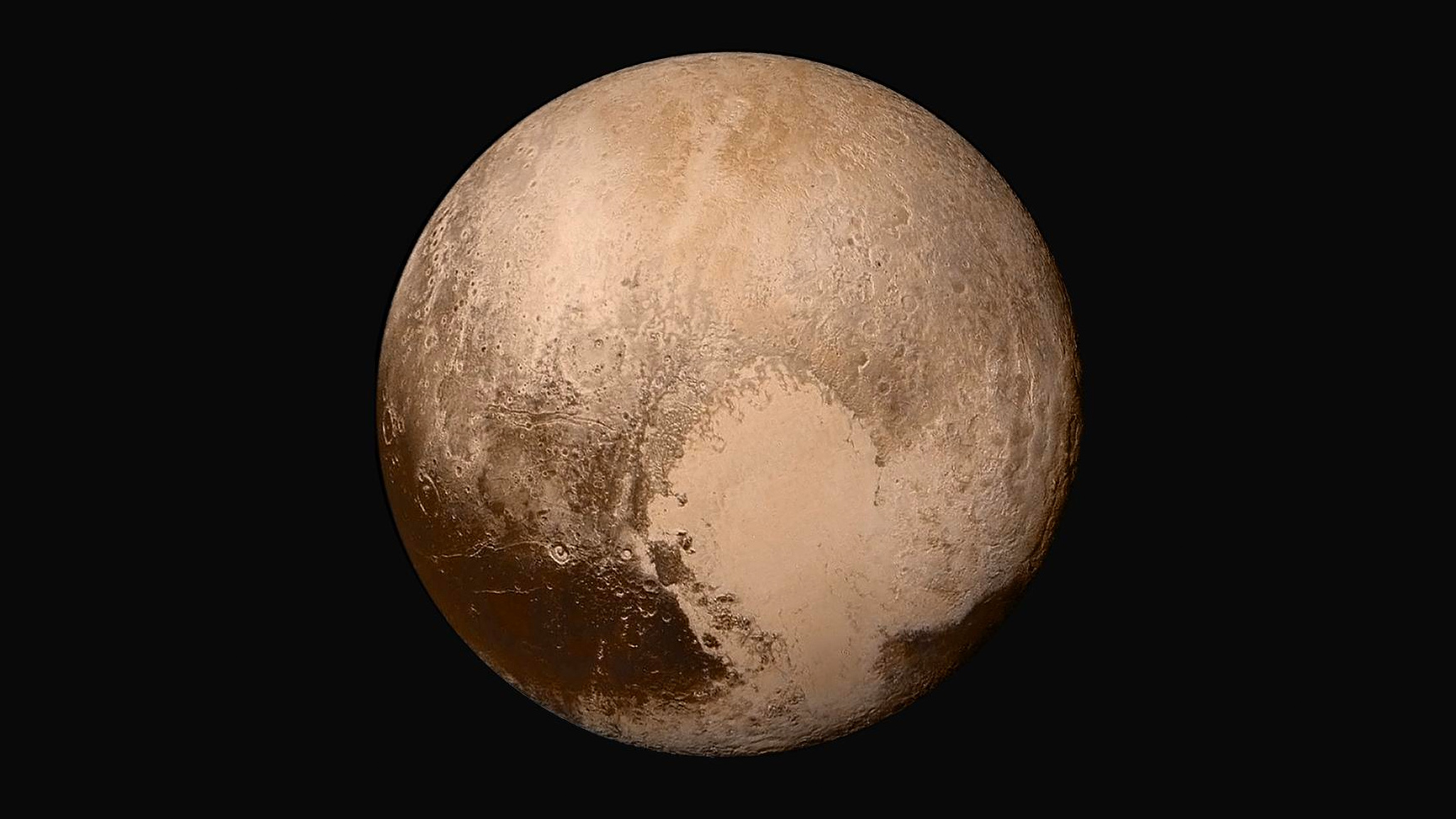

Pluto's icy heart is beating.

The dwarf planet's famous heart-shaped feature, which NASA's New Horizons spacecraft discovered during its epic July 2015 flyby, drives atmospheric circulation patterns on Pluto, a new study suggests.

Most of the action comes courtesy of the heart's left lobe, a 600-mile-wide (1,000 kilometers) nitrogen-ice plain called Sputnik Planitia. This exotic ice vaporizes during the day and condenses into ice again at night, causing nitrogen winds to blow, the researchers determined. (Pluto's atmosphere is dominated by nitrogen, like Earth's, though the dwarf planet's air is about 100,000 times thinner than the stuff we breathe.)

Related: Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons mission in pictures

These winds carry heat, particles of haze and grains of ice westward, staining the ices there with dark streaks.

"This highlights the fact that Pluto's atmosphere and winds — even if the density of the atmosphere is very low — can impact the surface," study lead author Tanguy Bertrand, an astrophysicist and planetary scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in California, said in a statement.

And that westward direction is interesting in itself, considering that Pluto spins eastward on its axis. The dwarf planet's atmosphere therefore exhibits an odd "retrorotation," study team members said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bertrand and his colleagues studied data gathered by New Horizons during the probe's 2015 close encounter. The researchers also performed computer simulations to model Pluto's nitrogen cycle and weather, especially the dwarf planet's winds.

This work revealed the likely presence of westerly winds — a high-altitude variety that races along at least 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) above the surface and a fast-moving type closer to the ground that follows Sputnik Planitia's western edge.

That edge is bounded by high cliffs, which appear to trap the near-surface winds inside the Sputnik Planitia basin for a spell before they can escape to the west, the new study suggested.

"It's very much the kind of thing that's due to the topography or specifics of the setting," planetary scientist Candice Hansen-Koharcheck, of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, said in the same statement.

"I'm impressed that Pluto's models have advanced to the point that you can talk about regional weather," added Hansen-Koharcheck, who was not involved in the new study.

New Horizons' Pluto flyby revealed that the dwarf planet is far more complex and diverse than anyone had thought, featuring towering water-ice mountains and weird "bladed" terrain in addition to the photogenic heart (whose official name, Tombaugh Regio, honors the discoverer of Pluto, Clyde Tombaugh).

The new study, which was published online Tuesday (Feb. 4) in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, reinforces and extends that basic message.

"Sputnik Planitia may be as important for Pluto's climate as the ocean is for Earth's climate," Bertrand said. "If you remove Sputnik Planitia — if you remove the heart of Pluto — you won't have the same circulation."

- Pluto flyby anniversary: The most amazing photos from NASA's New Horizons

- New Horizons probe's July 14 Pluto flyby: Complete coverage

- Ultima Thule in pictures: Flyby views of 2014 MU69 by New Horizons

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.