Pointy shoes destroyed rich people's feet in medieval England

Shoe pointiness reached extremes in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Being fashionable usually comes at a cost, and stylish people toward the end of the Middle Ages in Britain paid a steep price for wearing pointy shoes.

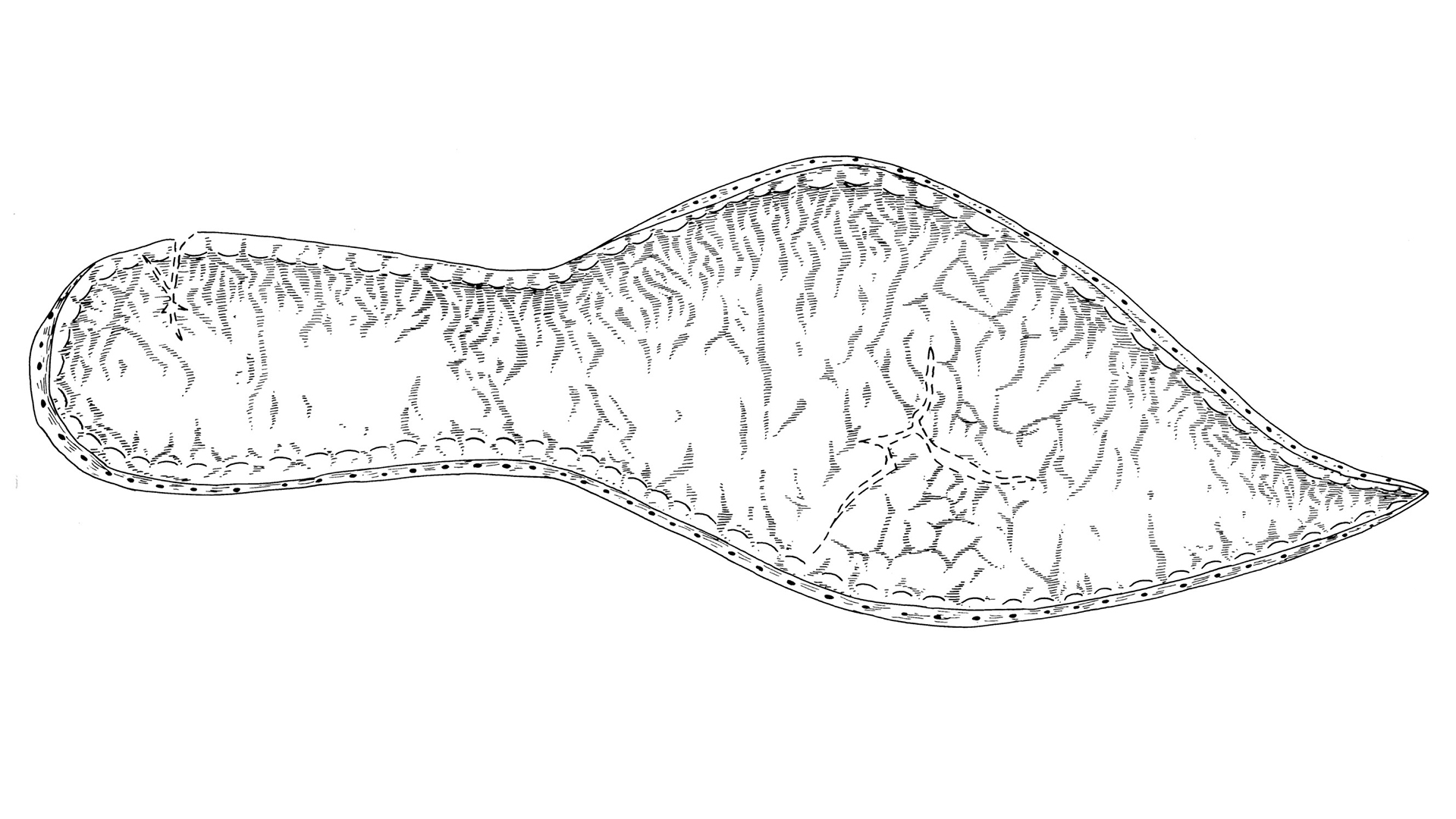

Pointy-shoe wearers often developed bunions, a type of foot deformity in which a bony mass forms at the base of the big toe and pushes that toe inward at an angle. While many factors can cause bunions, known medically as hallux valgus, this condition was far less common in the 13th century and earlier, when footwear styles were less extreme, according to a new study.

As these fashion victims grew older, they incurred other injuries, too. Bunions can lead to balance problems, and an examination of medieval skeletons showed that older individuals with bunions were also likely to have fractures in their upper limbs, from falls that were serious enough to break their bones.

Related: The 7 biggest mysteries of the human body

"The remains of shoes excavated in places like London and Cambridge suggest that by the late 14th century, almost every type of shoe was at least slightly pointed — a style common among both adults and children alike," said study co-author Piers Mitchell, an affiliated lecturer in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

"We investigated the changes that occurred between the high and late medieval periods, and realized that the increase in hallux valgus over time must have been due to the introduction of these new footwear styles," Mitchell said.

When a person develops bunions, the first sign of trouble is a "leaning" of the big toe toward the other toes so that it no longer points straight ahead, disrupting the toe bones' alignment, according to the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons (ACFAS). Bunions can develop because of arthritis or in response to other foot deformities, but the most common cause is "wearing shoes that crowd the toes," ACFAS says.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bunions can be painful, and the symptoms are progressive; if the conditions that cause bunions persist, the problem will worsen, according to ACFAS.

Recently, scientists wondered what archaeological evidence might reveal about foot problems in people who lived centuries ago. They analyzed the skeletons — and bunions — of 177 individuals from four medieval cemeteries in Cambridge, England. One cemetery was for wealthy friars and parishioners, one was a charitable graveyard for the poor, one was for burials of people who were neither rich nor destitute, and one was in a remote rural parish, the researchers wrote in a study published June 11 in the International Journal of Paleopathology.

The scientists also checked the skeletons for signs of injuries that may have been caused by balance loss resulting from bunions.

They found that 27% of the individuals dating to the 14th and 15th centuries suffered from bunions. About 45% of the friars in the wealthy cemetery had bunions — the highest percentage of the group — perhaps because around the 14th century it became more common for British clergy to dress fashionably, a trend that troubled high-ranking officials in the church, said Mitchell.

"The adoption of fashionable garments by the clergy was so common it spurred criticism in contemporary literature, as seen in Chaucer's depiction of the monk in the Canterbury Tales," Mitchell added. (Chaucer dressed his monk in a fur-trimmed robe adorned with a gold pin, and the character valued material comforts more than religion).

Overall, poorer people who couldn't afford to buy impractical shoes had healthier feet, according to the study. Bunions affected only 10% of the working poor in the main parish graveyard, and just 3% of the people in the rural cemetery. In skeletons dating to the 11th to 13th centuries, before pointy-toed shoes became a fad, only about 6% of the group had bunions, according to the study.

The skeletons of bunion sufferers also showed more signs of injuries, with about 52% of bunion sufferers having at least one fracture, the researchers reported.

"Modern clinical research on patients with hallux valgus has shown that the deformity makes it harder to balance, and increases the risk of falls in older people," lead study author Jenna Dittmar, a research fellow in human osteoarchaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, said in a statement. "This would explain the higher number of healed broken bones we found in medieval skeletons with this condition," added Dittmar, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Cambridge.

"We think of bunions as being a modern problem, but this work shows it was actually one of the more common conditions to have affected medieval adults," Dittmar said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.