10 times the US capital weathered political violence

Today's storming of the Capitol is still a standout in history.

Washington, D.C., is home to the nation's capital, as well as the aptly named Capitol building where the U.S. Senate and House create, debate and pass bills and help to govern the country. On Wednesday (Jan. 6), a mob of supporters for President Donald Trump, who falsely claimed he had won the election, stormed the Capitol building. But this isn't the first time the capital of the U.S. has seen political violence. From violent attacks on politicians, to a raging fire, to explosions, to indiscriminate shooting, Washington D.C. has seen its share of darkness.

1. Burning of Washington

![George Munger (1781–1825). [U.S. Capitol after Burning by the British], 1814.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/npMKDSELzaqYTZDCoC9CLQ.jpg)

During the War of 1812 against Britain, invading troops marched into Washington, D.C., and set the U.S. Capitol ablaze on Aug. 24, 1814, according to the U.S. Senate's historical highlights. The British soldiers also set fire to the President's Mansion and other U.S. landmarks with torches and gunpowder paste, leaving the capital city in ruins.

So, what saved D.C? A torrential rainstorm.

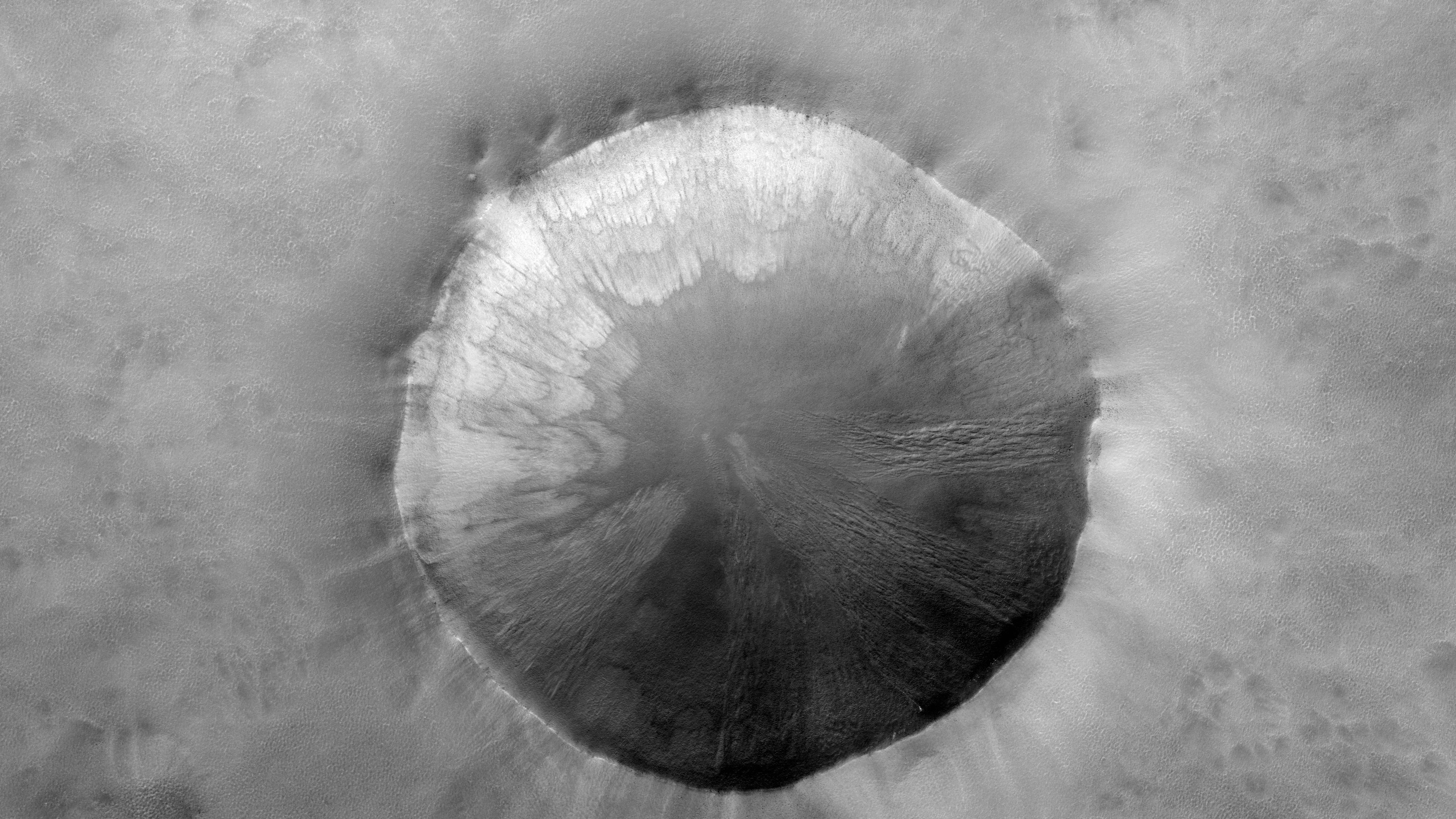

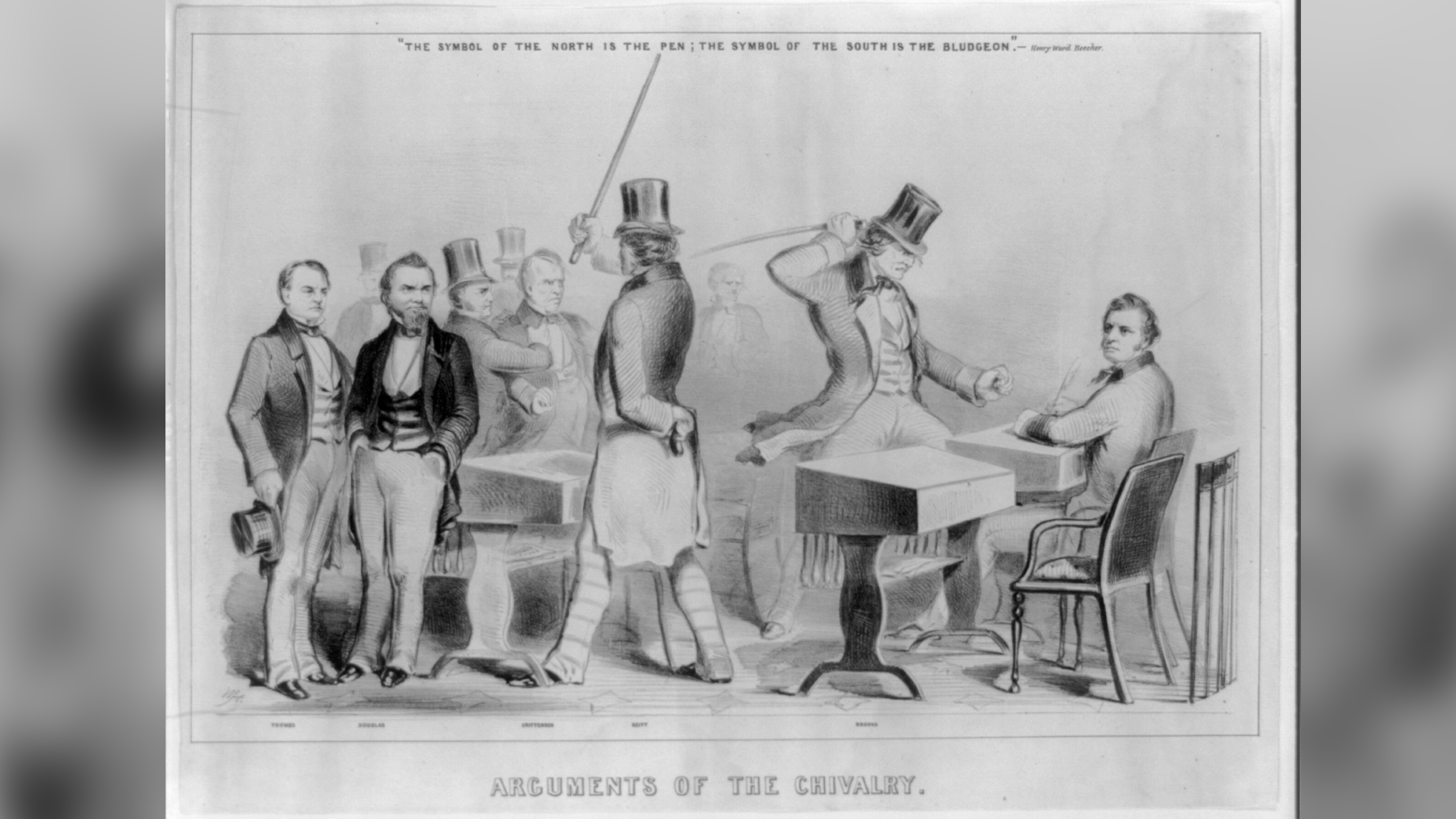

2. Political fighting (literally)

There's a long list of politically violent events that politicians instigated against each other. For instance, in 1856, U.S. Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina used a cane to brutally attack U.S. Sen. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, an abolitionist, following Sumner's rousing speech on whether Kansas should be a slave or a free state. In another instance, in 1902, junior Sen. John McLaurin of South Carolina called his state's senior senator, Ben Tillman, a liar. Tillman promptly punched McLaurin in the jaw, and "the chamber exploded in pandemonium as members struggled to separate both members of the South Carolina delegation," the U.S. Senate reported.

Political infighting began even before the U.S. Congress moved to D.C. In 1798, when the capitol was still in Philadelphia's Congress Hall, Rep. Roger Griswold of Connecticut was so mad that Rep. Matthew Lyon of Vermont spat tobacco juice at him, a fight erupted with each member holding a weapon (a cane and fire tongs, respectively).

There's more! In 1854, a "near-gun fight" happened on the House floor, and, in 1858, a fight led to one representative snatching the toupee off the head of another rep, allegedly claiming "Hooray, boys! I've got his scalp!"

3. Bomb explosion at Senate

On July 2, 1915, a former German professor at Harvard University, Eric Muenter, slipped into the Senate's Reception Room and left three sticks of dynamite. In fact, Muenter wanted to blow up the Senate Chamber, but that was locked, so he left the explosive materials in the adjacent room.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The bomb went off just before midnight, and no one was hurt (although a Capitol officer was knocked off his chair). Using an assumed name, Muenter framed his actions as an "appeal for peace" during World War I in a letter to the Washington Evening Star. After an assassination attempt against J.P. Morgan, Muenter was jailed, where he took his own life.

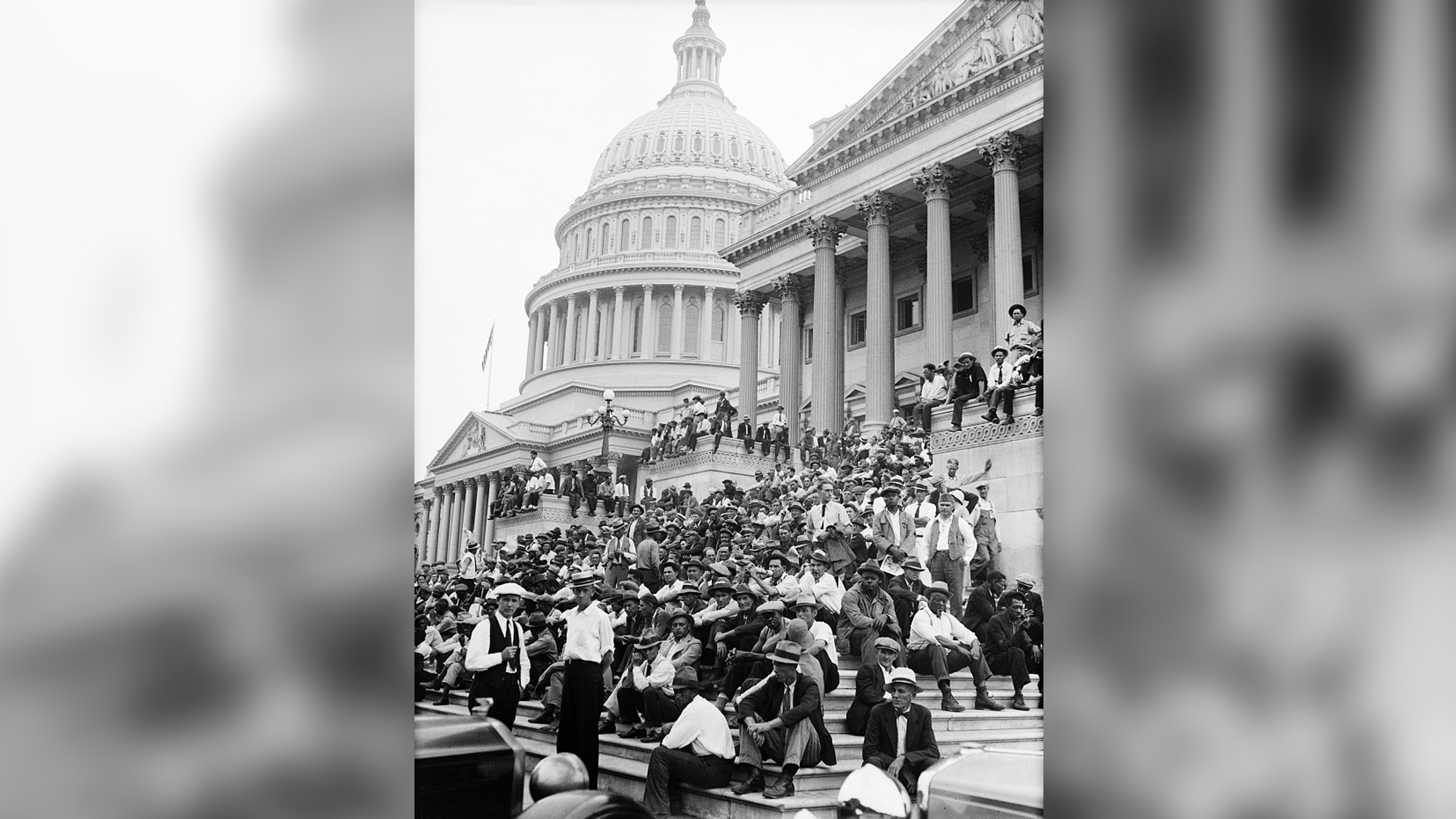

4. WWI vets go to Washington

Following World War I, about 25,000 U.S. veterans gathered outside Congress in 1932 in a bid to receive a salary bonus promised to them in previous legislation. Under that law, the bonus was scheduled for 1945, but the Depression meant the vets were desperate for money.

An expedited bonus passed the House, but not the Senate in 1932. The marchers were disappointed, but peacefully dispersed, with some setting up camps near Capitol Hill. That next month, armed federal troops, led by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Maj. Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton, "torched and gassed the veterans' camps, killing several and wounding many," according to the Senate's records.

5. Weather Underground bombings

In the early 1970s, the anti-Vietnam War group known as the Weather Underground planted a series of explosives around Washington, D.C., according to Encyclopedia Britannica. The group also detonated explosives in other major U.S. cities. Three of their founding members accidentally blew themselves up in 1970 while making bombs in New York City.

6. Puerto Rico separatists

On March 1, 1954, four Puerto Rican separatists entered the House floor during an upcoming vote. As part of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, these individuals wanted Puerto Rico to be independent, not a U.S. territory.

That afternoon, the Puerto Rican nationalists, armed with handguns, shot indiscriminately into the House, wounding five congressmen. All four assailants were later apprehended.

7. Bomb at Capitol building

In November 1983, a bomb ripped through the Capitol's north wing. Just before the blast, a caller claiming to be a member of the "Armed Resistance Unit" said the bomb had been planted to protest U.S. military actions in Grenada and Lebanon.

The bomb caused $250,000 in damages, but no one was injured. After a five-year investigation, charges were brought against six people believed to be behind the attack. After the bombing, security increased; previously, the area outside the Senate Chamber was open to the public, but now it's open only to those with clearance.

8. Attack at Capitol leaves two dead

In July 1998, an armed assailant broke past security and ran toward the office of then-Majority Whip Rep. Tom DeLay, of Texas. In their effort to stop the assailant, two Capitol Police officers died in the line of duty: Officer Jacob Chestnut, Jr., and Detective John Gibson.

A female tourist was also injured, as was the gunman, Russell Eugene Weston Jr., who was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and found unfit to stand trial, according to Forbes. Weston is now incarcerated at a federal medical center.

The two officers are buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

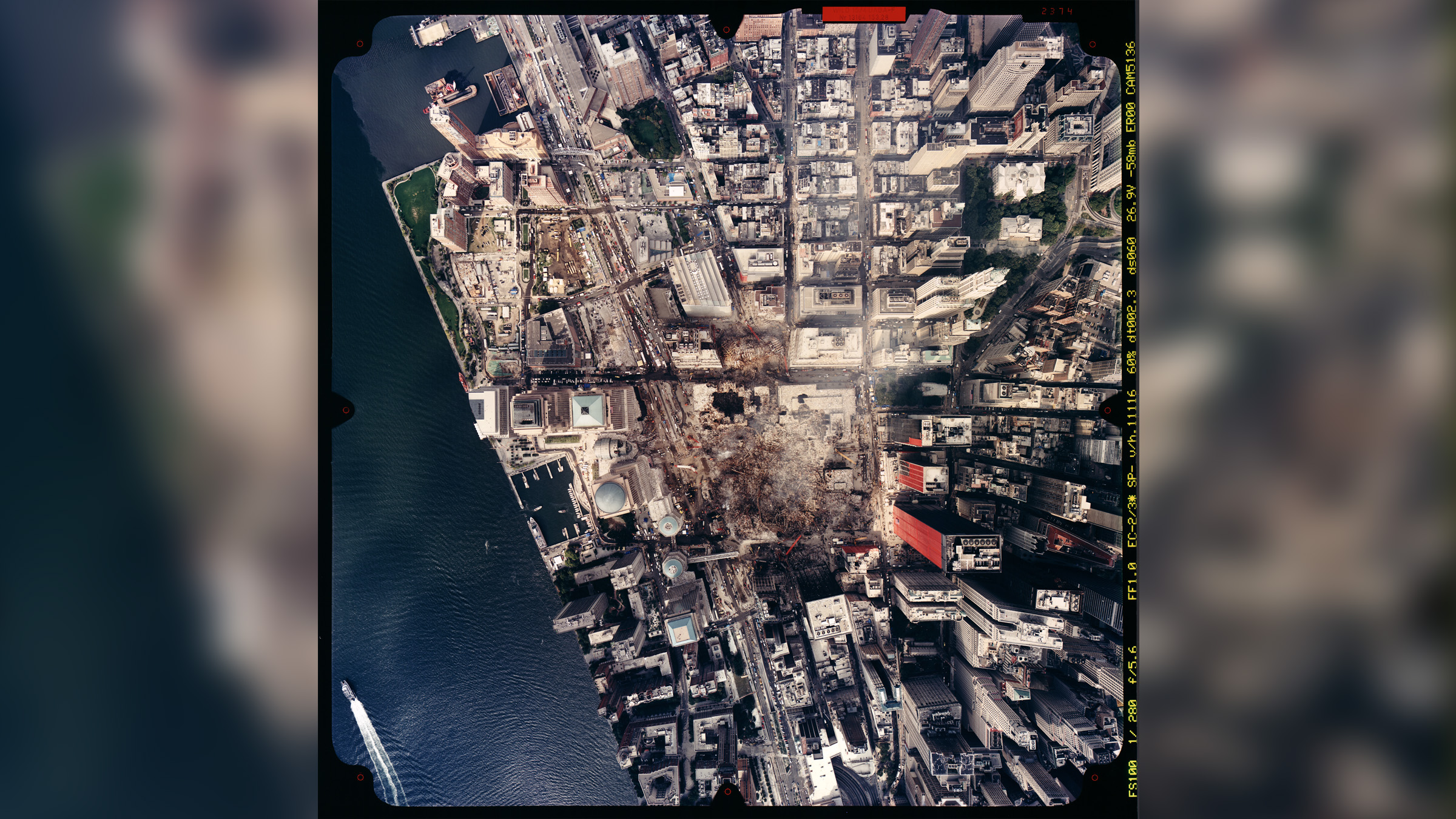

9. Sept. 11 and anthrax

On Sept. 11, 2001, tragedy swept the nation when terrorists hijacked commercial airplanes and crashed them into the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. A fourth plane, known as United Airlines Flight 93, crashed in Pennsylvania before it reached its intended target — likely the United States Capitol building, according to the National Park Service.

Shortly thereafter, the deadly bacteria anthrax was found on Capitol Hill, including in the office of Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle, of South Dakota, who was sent a letter laced with a fine white powder. Sen. Patrick Leahy, of Vermont, was also sent anthrax spores.

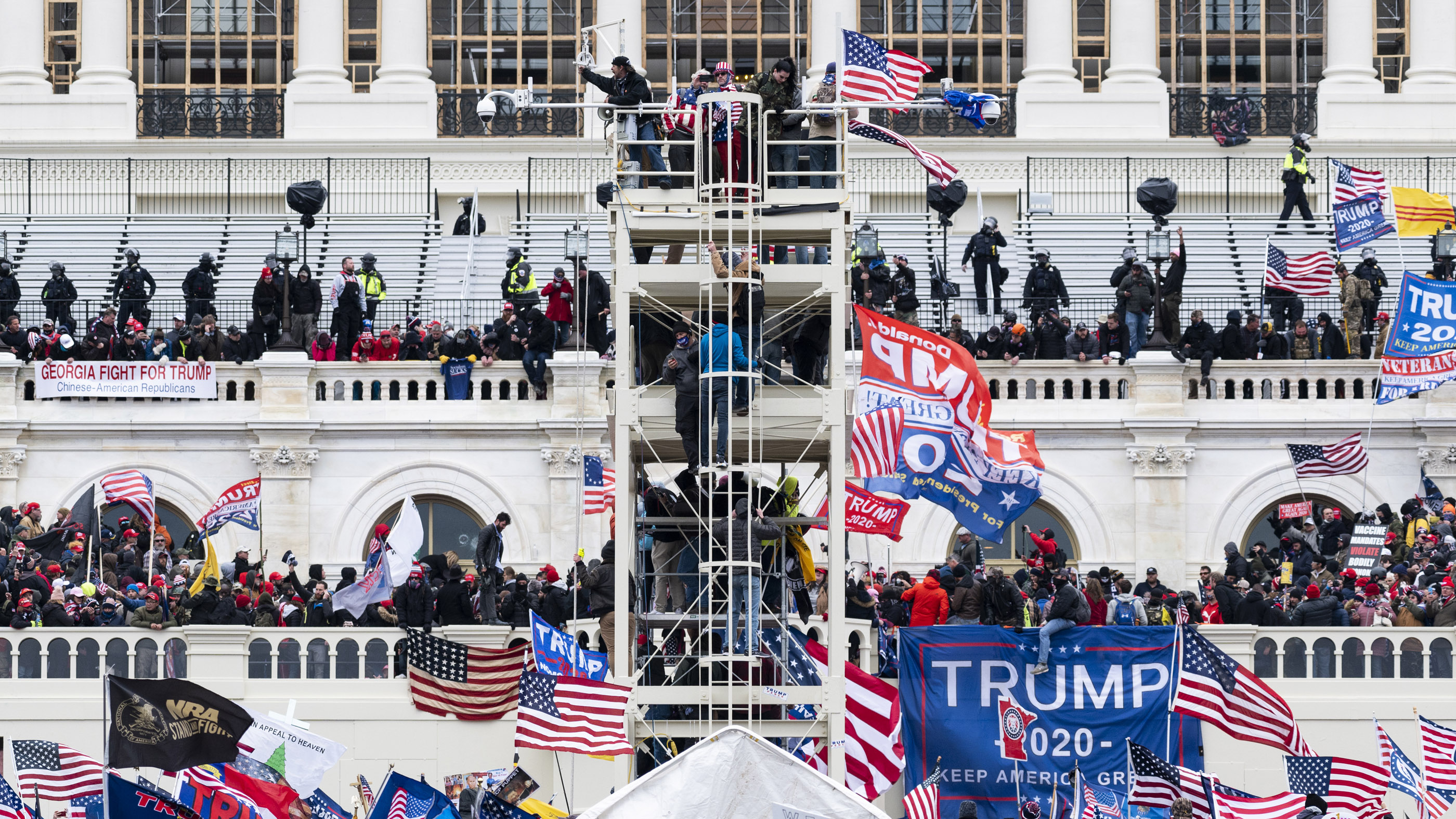

10. Mob invades Capitol building

On Jan. 6, 2021, supporters of President Trump stormed the U.S. Capitol after he urged them at a rally to march there, according to The Washington Post. They did this as the Senate was debating the electoral college votes that were expected to certify President-Elect Joe Biden's win. The pro-Trump group pushed past police, sending the Senate into an unscheduled recess.

Multiple politicians tweeted about the mob, including Rep. Dan Kildee, of Michigan.

"I am in the House Chambers. We have been instructed to lie down on the floor and put on our gas masks. Chamber security and Capitol Police have their guns drawn as protesters bang on the front door of the chamber.

This is not a protest. This is an attack on America."

During the chaos, a woman was shot and later died, The New York Times reported.

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 2:45 p.m. EST on Jan. 7 to correct the date from Jan. 6, 2020 to Jan. 6, 2021 for the day the pro-Trump mob stormed the U.S. Capitol.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.