Polynesians and Native Americans paired up 800 years ago, DNA reveals

About 800 years ago, long before dating apps existed, Polynesians from the South Pacific and Native Americans from what is now Colombia hooked up, creating a genetic signature that still exists in some Polynesians today, a new genetic study finds.

Here's the kicker, though: Scientists aren't sure where this coupling happened. It's possible Native Americans traveled to Polynesia, or alternatively, Polynesians boated to the region that is now Colombia, and then returned to Polynesia, taking their Polynesian-Native American children (and maybe even a few Native Americans) with them, the researchers said.

"We can't say definitely who made contact with whom," study lead researcher Alexander Ioannidis, a postdoctoral research fellow of biomedical data sciences at Stanford University, told Live Science.

Related: 10 things we learned about the first Americans in 2018

Scientists have long wondered about prehistoric contact between the Polynesians and Native Americans. Several clues suggest that the islanders and mainlanders connected at some point; for instance, New World crops, including the sweet potato and bottle gourd, are found in the Polynesian archaeological record.

In 1947, the Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl even showed the journey was possible with the Kon-Tiki expedition, when he boated on a wooden raft more than 4,300 miles (7,000 kilometers) over 101 days from Peru to Polynesia.

However, several genetic studies have produced conflicting conclusions about whether Native Americans had contact with Polynesians prior to the arrival of Europeans on an island in east Polynesia called Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, in 1722. However, these studies tended to have small sample sizes and to look only at certain parts of the genome.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

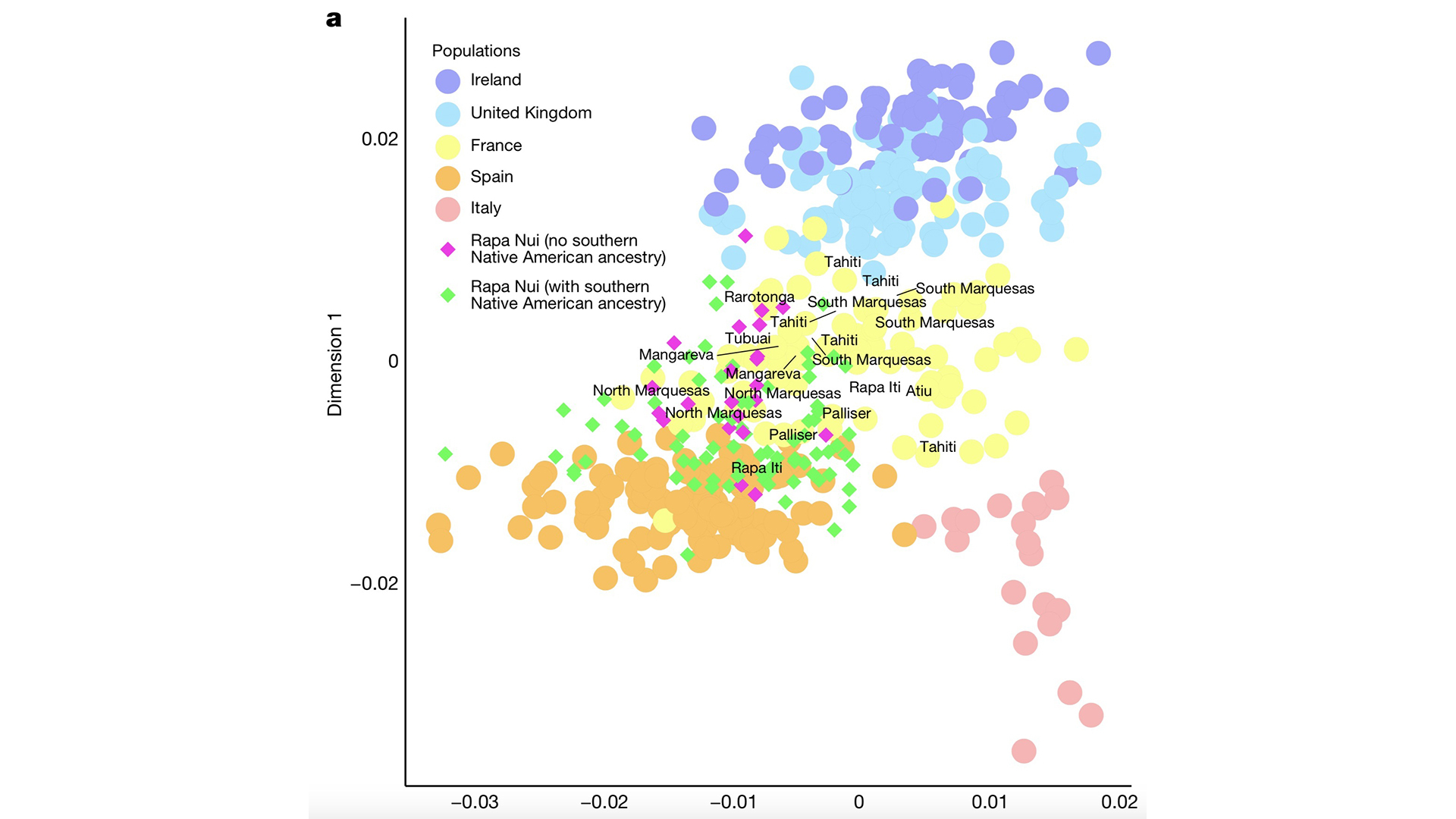

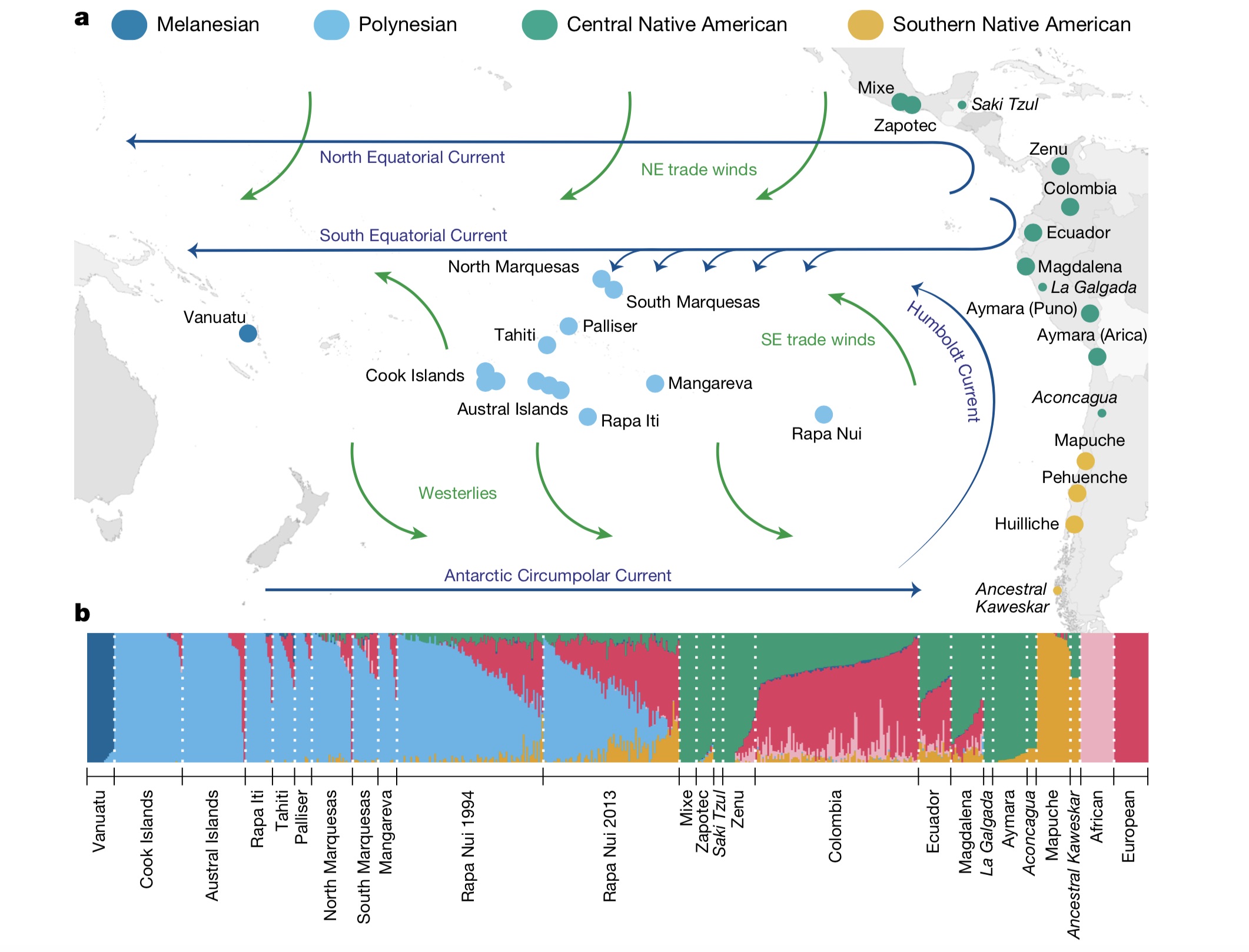

In the new study — the largest and the first genome-wide analysis to tackle the Polynesian-Native American mystery — researchers looked at 807 Indigenous individuals from 17 populations spanning the Pacific Islands (which included Polynesian islands and Vanuatu, in Melanesia) and 15 Native American groups from the Pacific Coast of South America. Their results showed "conclusive evidence for prehistoric contact of Polynesian individuals with Native American individuals (around A.D. 1200) contemporaneous with the settlement of remote Oceania" (a region that includes Polynesia), the researchers wrote in the study.

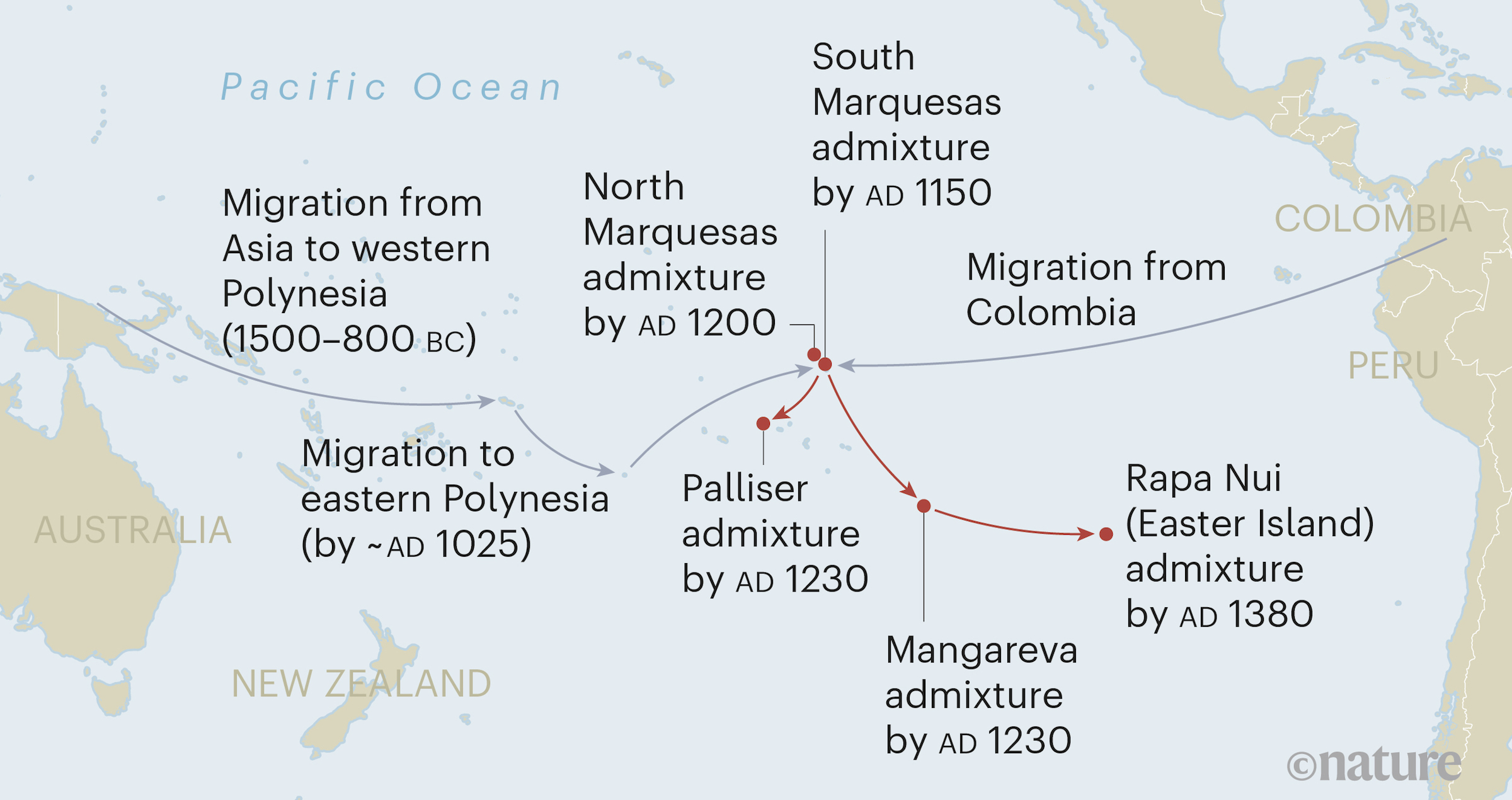

However, even though Rapa Nui is the closest Polynesian island to South America, it was not the first place to host people with Polynesian-Native American ancestry, the researchers found. Rather, the researchers found evidence that by 1150 Polynesian-Native Americans had reached the South Marquesas, more than 2,200 miles (3,500 km) from Rapa Nui. From there, these ancient people moved on, reaching the North Marquesas by 1200, Palliser and Mangareva by 1230 and finally Rapa Nui by 1380.

Image Gallery (5 images)

Genetic puzzle

After collecting DNA from the study participants — a huge endeavor that included radio advertisements and in-person meetings in Polynesia — the scientists teased apart which snippets of DNA came from Indigenous Polynesian ancestry and which snippets came from outside sources, such as from European or African descent. (The graphic below is a helpful illustration of this.) In other words, after establishing a background "reference," the scientists knew which DNA sequences came from which populations.

In particular, the team zeroed in on Native American sequences found in Polynesian genomes. A previous 2014 study in the journal Current Biology had shown that Native American DNA became part of some Polynesians genomes from about 1300 to 1500, but that research didn't pinpoint which region of South America those Indigneous people came from. In the current study, the researchers identified that the Indigenous signal was similar to that of the Zenu, a Native American group that lives in Colombia.

Related: Image gallery: Walking Easter Island statues

The team then used several statistical methods to figure out when in history the Polynesians had coupled with the Native Americans. "All of those dating methods gave the same date, which is the Middle Ages, around 1200," Ioannidis said. "That was long before Europeans came onto the scene."

This is an important detail, the researchers said, as thousands of Pacific Islanders, including 1,407 Rapa Nui individuals, were kidnapped during the Peruvian slave raids of 1862-1863. Of those captured, about 20 returned to Rapa Nui. In addition, Rapa Nui became a Chilean territory in 1888. It's possible that these events prompted Polynesian-Native American coupling, which would have introduced Native American DNA into the following generations' genomes. Some people have argued that such couplings would explain why some Polynesians have Native American DNA, Ioannidis said.

In contrast to those recent dates, the new results indicate that the Polynesian-Native American coupling was a single event in the deep past that involved multiple couples. After that event, the Polyesians' descendants, who carried Native American DNA in them, went on to explore distant Polynesian islands, including Rapa Nui. As a result, their descendants still carry some Native American DNA.

However, not all modern Polynesians carry Native American ancestry; the researchers found the signal predominantly on several eastern Polynesian islands, which were likely settled after the coupling event happened, the researchers said.

Wind and ocean currents

The genetic study doesn't reveal where the coupling event took place, and neither do the wind or ocean currents, the researchers noted. Both journeys — from Polynesia to Colombia, and from Colombia to Polynesia — are possible based on modern wind and water patterns.

The ancient Polynesians were known to have boated upwind, so that if they needed to turn around they could easily reverse course, study senior researcher Dr. Andrés Moreno-Estrada, a professor of genetics at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity (LANGEBIO) at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute (CINVESTAV) in Mexico, told Live Science.

Moreover, the trade winds and the south equatorial ocean current move east to west from Colombia, which would have funneled voyagers from Colombia to the Polynesian Marquesas islands.

Related: In photos: Human skeleton sheds light on first Americans

When the study came out yesterday (July 8) in the journal Nature, Moreno-Estrada and his colleagues presented the results to the study participants in Polynesia over a Zoom call at Rapa Nui Museum.

In an accompanying "News and Views" opinion piece published in the same issue of Nature, Paul Wallin, an archaeologist at Uppsala University in Sweden, who was not involved in the study, wrote that, from an archaeological standpoint, it's now important to see whether this proposed genetic model "fits with material-culture studies, ethno-historical records, linguistics and evidence of plant and animal distributions." All of this data could strengthen and shed light on the connection between Native Americans and Polynesians.

Wallin added that humans likely first settled Rapa Nui by 1200 at the latest. However, because the coupling event on Rapa Nui is dated to about 1380, it's likely that that the island was "already populated by other Polynesians," Wallin wrote.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.