First-known pregnant mummy discovered

The researchers expected to discover the remains of a male priest.

Researchers have discovered the world's first-known pregnant mummy, dating from the first century in Egypt. The find was unexpected, as inscriptions on the mummy's coffin suggested the remains inside belonged to a male priest, according to a new study.

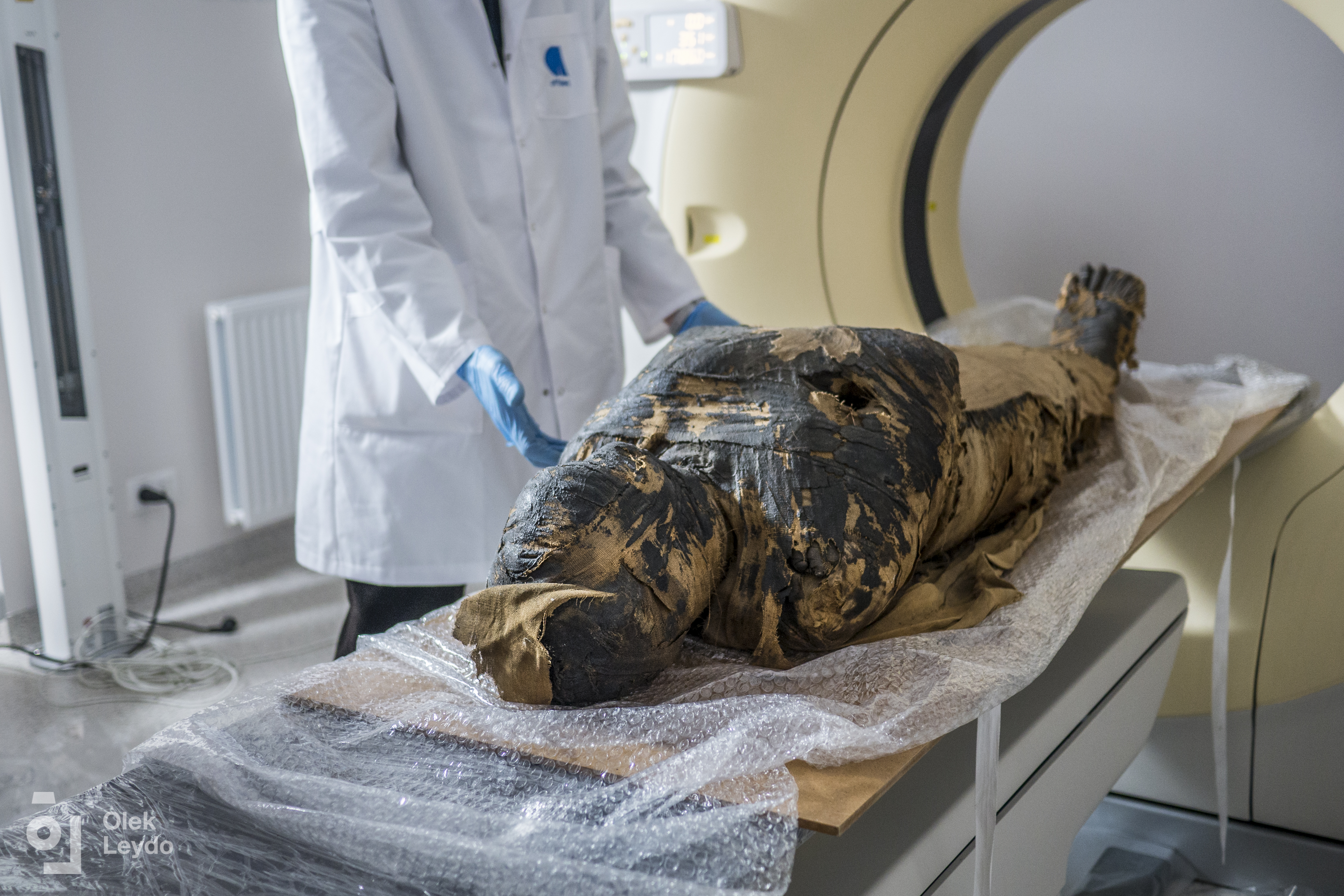

The mummy was donated to the University of Warsaw in Poland in 1826; only recently did archaeologists with the Warsaw Mummy Project conduct a detailed analysis of the mummy while studying the National Museum in Warsaw's collection of animal and human mummies.

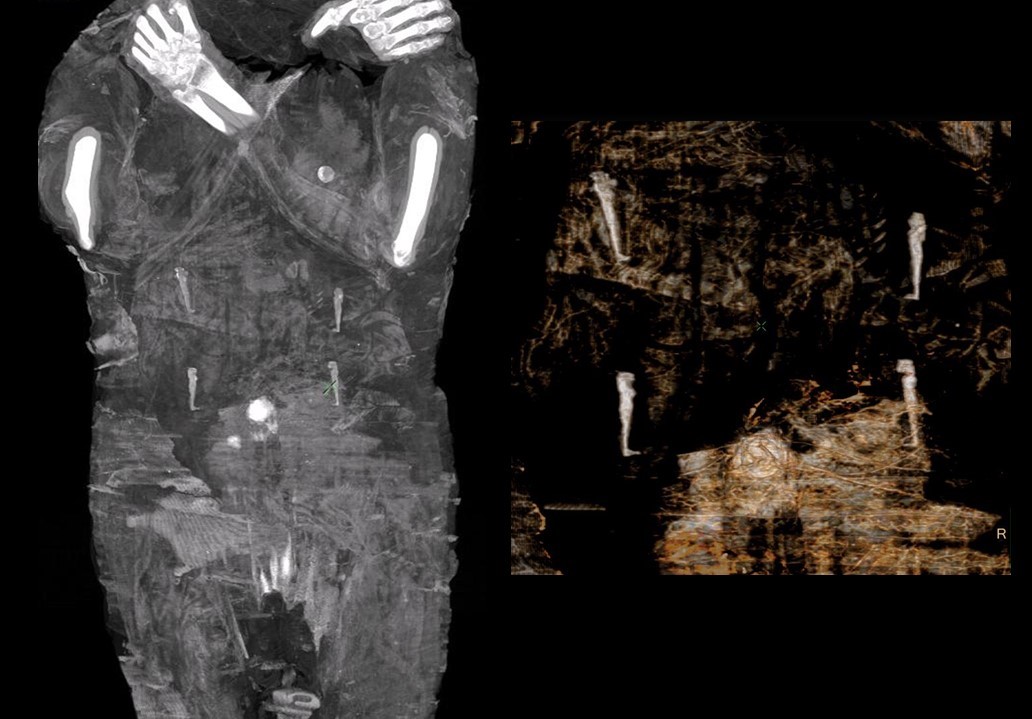

X-ray and CT scans of the mummy revealed that the remains inside belonged to a female and did not match the coffin and cartonnage case that was made for a male. The mummy was obviously not the remains of a priest named Hor-Djehuty from ancient Thebes, whose name was inscribed onto the coffin, the researchers said.

Related: Photos: 1,700-year-old Egyptian mummy revealed

"It was complete surprise because we were looking for ancient diseases or causes of deaths," lead author Wojciech Ejsmond, co-director of the Warsaw Mummy Project said. "Also, we thought that this is a body [of] a priest."

The mummy turned out to be the remains of a female who died when she was between 20 and 30 years of age and was about 6.5 to 7.5 months pregnant, based on the circumference of the fetus's head.

"It's the first such preserved case," Ejsmond told Live Science in an email. There have previously been skeletons of pregnant women found, but no mummies with preserved soft tissue, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scans showed four mummified bundles — likely her lungs, liver, stomach with intestines, and heart — inside the female mummy. Those were extracted, embalmed and then placed back inside the mummy's abdominal cavity, which was a customary practice in ancient Egypt. But the fetus had not been similarly removed from the uterus.

The researchers haven't determined the sex of the fetus or why it was left in the womb.

The researchers hypothesize that the fetus may have been thought of as "still an integral part of the body of its mother, since it was not yet born," according to the study. A baby that didn't yet have a name may not have been thought of as a distinctive individual, as ancient Egyptian beliefs held that naming was an important part of being human.

"Thus, its afterlife could only have happened if it had gone to the netherworld as part of its mother," the authors wrote. Another hypothesis is that a fetus of that age would have been difficult to extract due to the thickness and hardness of the uterus, and so the people mummifying the mother may not have been able to extract the fetus without damaging her body or that of the fetus, they wrote.

The archaeologists are also not sure why this mummy was inside a male's coffin; however, it's thought that up to 10% of mummies are found in the "wrong" coffins, due to illegal excavations and looting, according to the study. What's more, there was damage to the wrappings on the mummy's neck, likely caused by robbers who may have stolen some amulets, according to the study.

The authors have called her the "Mysterious Lady of the National Museum in Warsaw" because there's still much that’s unknown about her. "Her mummy represents a fine example of ancient Egyptian embalming skills, thus suggesting her high social standing," the authors wrote. She was also buried with a "rich set" of amulets, according to the study.

It's also not clear why she died. "High mortality during pregnancy and childbirth in those times is not a secret," Ejsmond told Science in Poland. "Therefore, we believe that pregnancy could somehow contribute to the death of the young woman."

The team now hopes to analyze small samples of blood that were preserved in the mummy's soft tissues to try to figure out the cause of death.

This find "allows us to gather first hand evidence" of prenatal health in ancient times, Ejsmond told Live Science. "We can make comparative studies with contemporary cases, look for traces of ancient medical procedures to study the history of medicine."

The findings were published April 28 in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.