Face of ancient Egyptian 'Mysterious Lady' mummy revealed in stunningly lifelike reconstructions

The identity of an Egyptian mummy has baffled archaeologists for centuries. Now they know what she may have looked like.

The mummy of a woman who may have been pregnant when she died has baffled archaeologists in search of clues about her true identity. Now, two facial approximations by forensic specialists are offering new insight into what this ancient Egyptian woman may have looked like, disclosing yet another secret that she held onto for centuries.

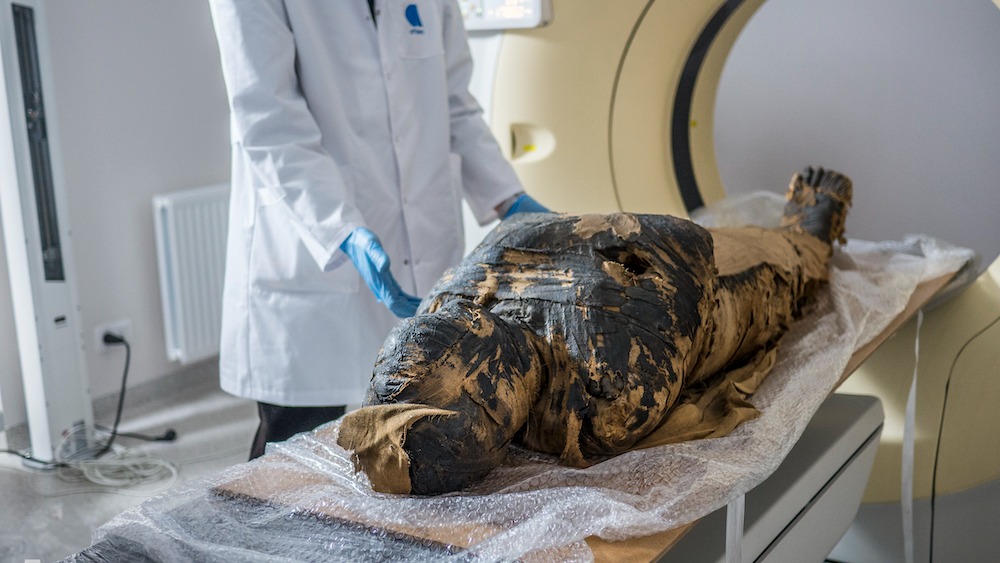

Using CT scans and X-rays, forensic specialists worked on facial reconstructions of the mummy, resulting in two different interpretations of the woman's likeness. In both reconstructions, the dark-skinned young woman with brown eyes is seen looking straight ahead, providing a realistic image of her lost in thought.

"Modern techniques enable us to perform a virtual autopsy of the mummy," Wojciech Ejsmond, co-director of the Warsaw Mummy Project, told Live Science in an email. "We can look under the bandages and inside her body. For the first time her face will be [revealed] to the general public and everyone will be able to look at her face."

The Warsaw Mummy Project in Poland published the facial approximations in a Nov. 8 Facebook post.

Related: Signs of cancer found in mysterious 'pregnant' Egyptian mummy

"Whether an archaeological or a forensic facial reconstruction is being carried out, facial reconstruction shouldn't be considered an exact portrait of the individual," Chantal Milani, a forensic specialist who worked on the project, told Live Science in an email. "However, it's based on the principle that the skull, like most anatomical structures, has details, proportions and shapes that are individual to that person and will manifest themselves through the soft tissues, adding personal character to the final appearance."

She added, "The face that covers the bone structure follows different anatomic rules, thus standard procedures can be applied to reconstruct it, for example to establish the shape of the nose. The most important element is the reconstruction of the thickness of the soft tissues at numerous points on the surface of the facial bones. For this, we have statistical data for various populations across the globe."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fellow forensic specialist and project member Hew Morrison agreed, adding, "In a historical context, the process helps to figuratively bring the deceased back to life," he told Live Science in an email, "thus, fostering respect and sensitivity for the deceased who are either the subject of research or are being exhibited in museums."

The facial reconstructions provide more insight into a woman whose identity continues to elude archaeologists, who at one time thought the mummy belonged to a male priest.

Last year, researchers from the Warsaw Mummy Project released a study about the mummy, dubbing her the "Mysterious Lady," since little was known about her. In the early 19th century, archeologists found her remains inside a sealed sarcophagus belonging to a male priest, which they donated to the University of Warsaw in 1826. After conducting a CT scan of the body nearly two centuries later, researchers realized that they were looking at perhaps the world's first known pregnant mummy, who appeared to be about 28 weeks pregnant and in her 20s when she died. They also concluded that she may have had cancer.

The controversial claim received pushback from members of the archaeological community, including some who said the "fetus" — which didn't have skeletal bones or a defined body shape — was actually warped embalming packs. But that didn't deter the researchers from wanting to learn more about the woman who was buried so long ago.

"For many people, ancient Egyptian mummies are museum curiosities," Ejsmond said. "We would like to rehumanize them and show them as once living, feeling and loving persons, whose deaths were tragedies."

The facial reconstructions, as well as a holographic depiction of the woman, are part of an exhibition being held at the Silesian Museum in Katowice, Poland, and will be on display through March 5, 2023.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.