Prehistoric rock carvings may have been the first cartoons in history, new study suggests

Animal portraits may have been placed close to flickering fires to appear animated.

The world's oldest moving pictures may not come from the late 19th century, but rather from thousands of years earlier: Pictures of ancient animals carved onto flat stones tens of thousands of years ago were deliberately placed around fires so they would look animated in the flickering firelight, a new study suggests.

Creating such animated carvings might have been a popular prehistoric activity as a family group sat around a fire. And at least some of the wall paintings and carvings found in ancient caves might also have been influenced by their appearance in the moving light and shadows of flames, the study suggests.

“When you get this dynamic light across the surface, suddenly all these animals start to move; they start to flicker in and out of focus,” archaeologist Andy Needham of the University of York in the United Kingdom told Live Science.

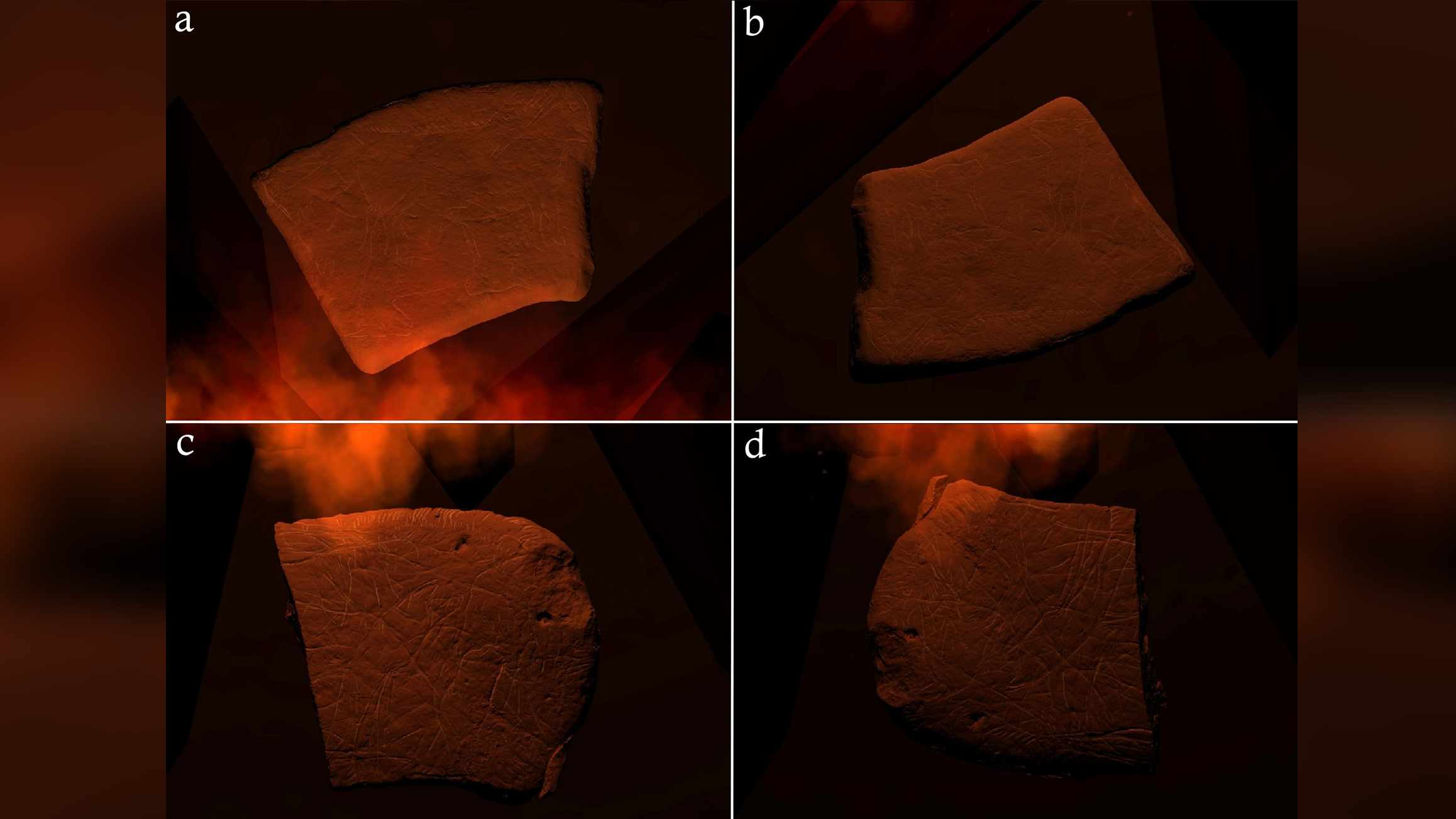

Needham is the lead author of a study published Wednesday (April 20) in the journal PLOS ONE that describes how some of the animal portraits carved on flat limestone rocks at a prehistoric shelter in southern France were exposed to hearth fires after they were made.

The study suggests the carvings were crafted primarily to be "animated" by the firelight; and the researchers have now created movies from their findings that show the effect, with firelight dancing across a precise 3D model of a carved plaquette adorned with engravings of wild horses.

“The interaction of engraved stone and roving firelight made engraved forms appear dynamic and alive, suggesting this may have been important in their use,” the researchers wrote in the new study. “Human neurology is particularly attuned to interpreting shifting light and shadow as movement and identifying visually familiar forms in such varying light conditions.”

Animal engravings

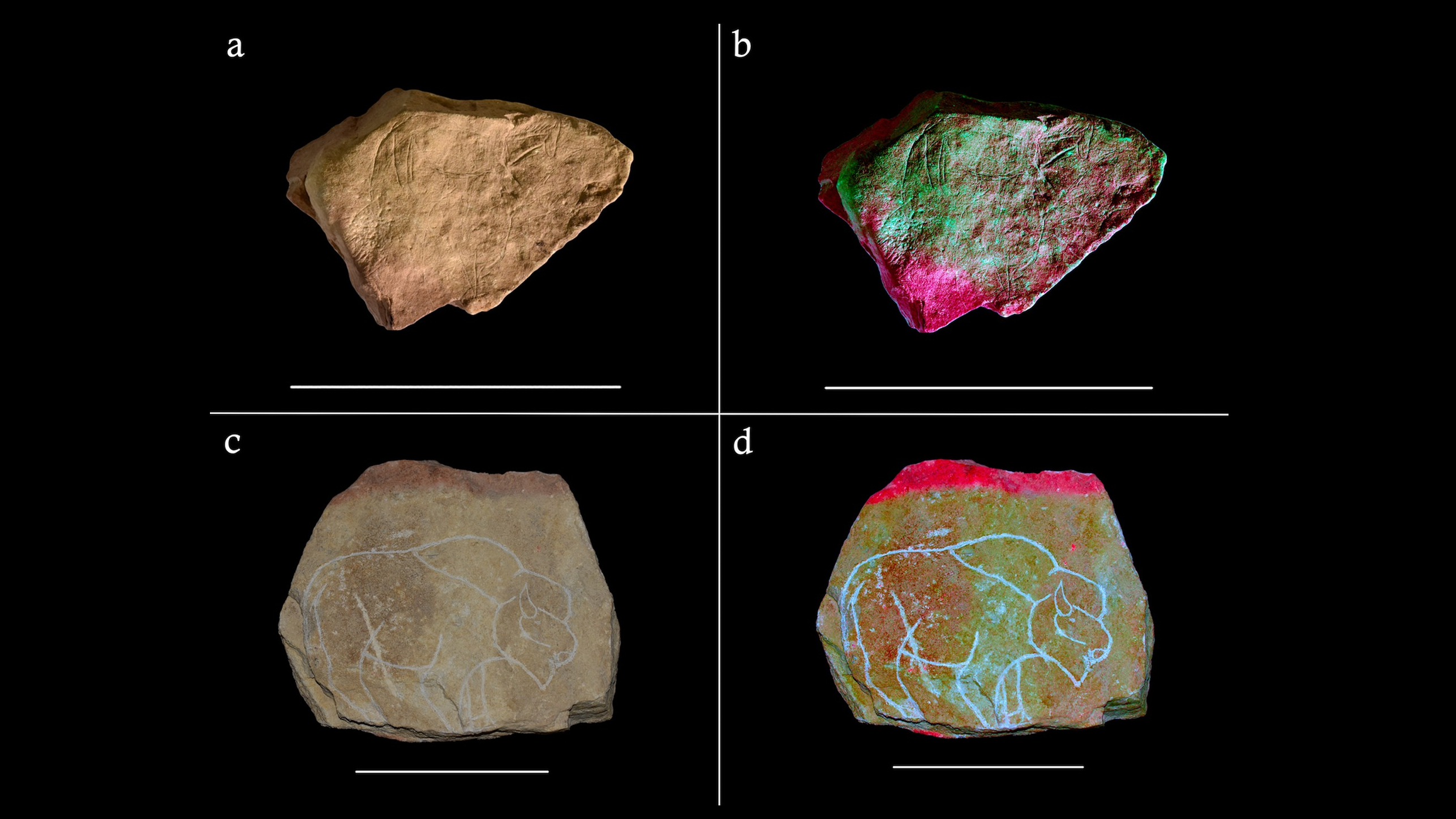

Needham and his colleagues used modern scanning technology and virtual reality techniques to study 50 limestone “plaquettes” – flat, carved rocks – that were excavated in the mid-19th century at the Montastruc rock shelter in southern France; they are now held at the British Museum in London. Together, the plaquettes are covered with 77 naturalistic carvings of wild animals, including horses, chamois, reindeer, and bison. Scientists think that Homo sapiens made the engravings during the Magdalenian epoch of the Late Upper Paleolithic period, between 12,000 and 16,000 years ago.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Needham had noticed that many of the carved plaquettes were damaged by fire – some were covered by layers of white ash, while others were scorched or cracked by heat. On a closer inspection, many showed “rubefaction” – bands of pink discoloration that result from heating iron deposits in the stone, he said. And many of the animal engravings were superimposed on each other.

“Rather than ignoring or engraving over previous depictions, animals were often melded together or fitted around each other,” the researchers wrote.

Sometimes the animal’s body parts were recycled, such as in one plaquette that shows a both a horse and a bovid (some type of wild cattle): “The abdomen and neck of the horse form the back and neck of the bovid, while the head of the horse forms the ear of the bovid,” the researchers wrote in the study.

“Paleolithic television”

Needham and his colleagues suggest the prehistoric plaquettes from Montastruc, and possibly at other sites, were placed around the hearth of a fire so that the portrayals of animals carved on them might appear animated in the flickering firelight

There’s also evidence of markedly different levels of artistic skill in portraying the animals, and that suggests a “diversity of authorship” of the carvings – in other words, they were made by several different people.

That, in turn, could suggest that the practice of carving animals onto the plaquettes and then placing them around the fire to be animated might have been a social activity, he said.

“It may be that many people within the community were sat around doing this,” he said. “It’s almost like Paleolithic TV.”

Study coauthor Izzy Wisher, an archaeologist at Durham University in the U.K., agreed that the engravings on the rocks and the evidence they were subsequently heated suggest they were intended to look animated.

“I think part of the reason why they may have been overlaying animals in this way was exactly to create this animation effect,” she told Live Science. “Sometimes you see not the same animal, but multiple animals in different orientations… so one would become visible, and then another, and then a different one, which really creates a sense of narrative around these engraved forms.”

Similar practices may also have influenced some of the ancient paintings on the walls of caves – such as at the stunning Chauvet Cave in southeastern France, where many of the animal portraits are similarly overlaid on each other and some seem to show signs of being heated by fires underneath them, she said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.