Rare fossilized vomit discovered in Utah's 'Jurassic salad bar'

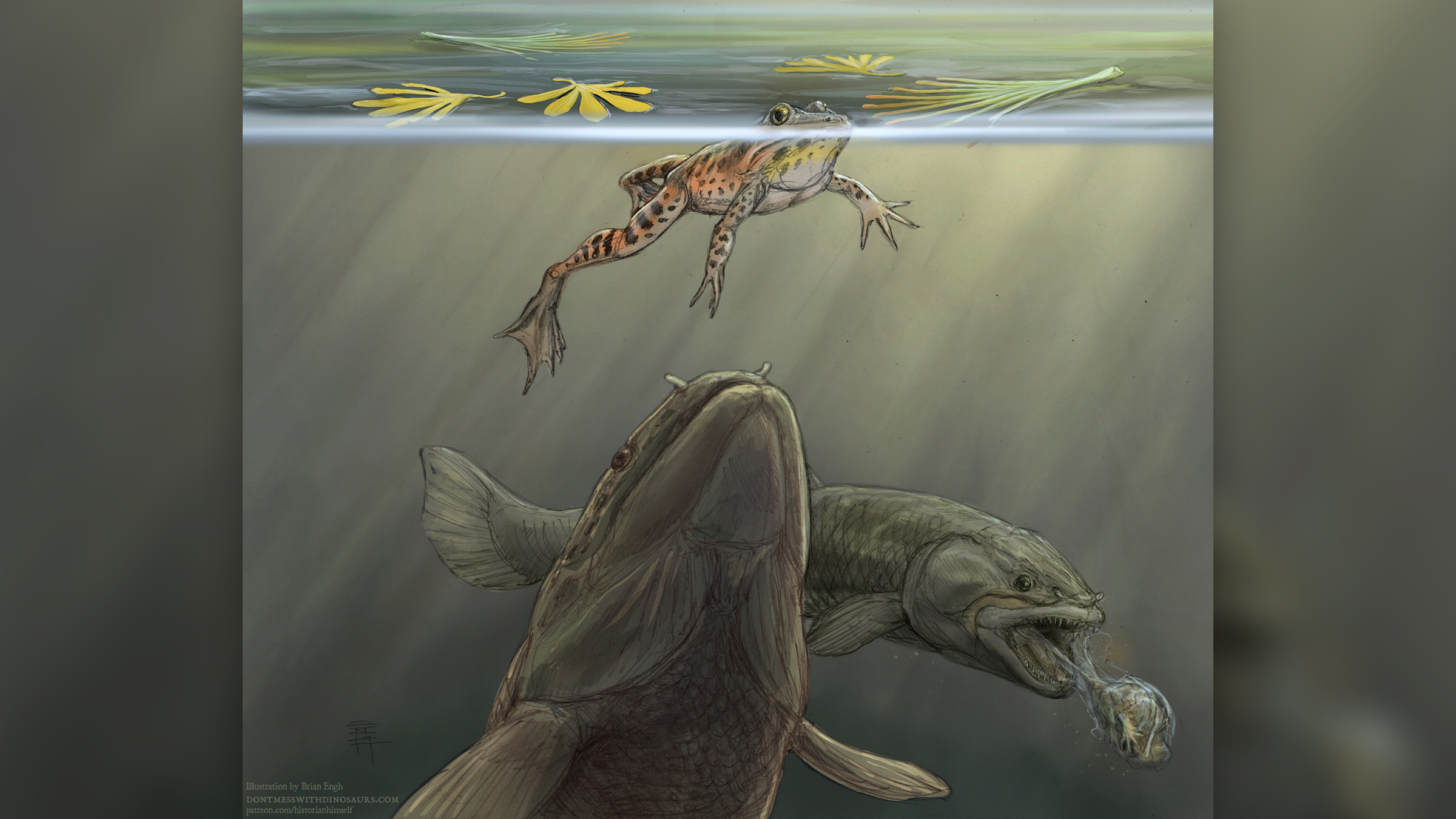

Salamander and frog: It's what's for dinner.

Hundreds of millions of years ago, a carnivorous critter gorged on a feast of prehistoric amphibians — and puked up its meal afterward. Now, paleontologists have unearthed the regurgitation and published their findings of the ancient upchuck.

In 2018, researchers discovered the regurgitalite — fossilized remains of an animal's stomach contents, also known as a bromalite — during an excavation in the southeastern Utah portion of the Morrison Formation. This swath of sedimentary rocks that stretches across the Western United States is a hotbed for fossils dating to the late Jurassic period (164 million to 145 million years ago). This section in particular, dubbed the "Jurassic salad bar" by local paleontologists, typically contains the fossilized remains of plants and other organic matter, rather than animal bones.

So, when a team that included researchers from the Utah Geological Survey (UGS) stumbled upon the "compact little pile" of retched remains measuring no more than one-third of a square inch (1 square centimeter), they knew they had found something special, the scientists reported in a study, published Aug. 25 in the journal Palaios.

"What struck us was this small concentration of animal bones in a relatively tiny area," lead author John Foster, a curator with the Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum in Vernal, told Live Science. "Normally there are no animal remains at this site, only plants, and the bones we did find weren't spread out [amongst the rock] but were concentrated to this one spot. These are the first bones we've ever seen there."

Related: Ginormous Jurassic fossil in Portugal may be the biggest dinosaur ever found in Europe

Initially, the team didn't know they had found prehistoric vomit. Instead, the scientists thought they had discovered the bones of one critter, until they "realized that some of them looked wrong and weren't all from a single salamander," Foster said. "Looking closer, most of the material is from a frog and at least one salamander. It was then that we started suspecting that what we were seeing was puked out by a predator."

Those remains include amphibian bones, specifically femurs from a frog and a salamander, as well as vertebrae from one or more unidentified species. All told, nearly a dozen bone fragments were found clustered together, along with a matrix of fossilized soft tissues, according to the study. And unlike coprolites (fossilized poop), this regurgitation isn't completely digested, leading researchers to determine that it’s a regurgitalite.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although there have been a number of recorded findings of regurgitalites around the world, Foster said that this is the first known instance of one at the Morrison Formation, calling the discovery "one of a kind." While there's no way of knowing exactly which species of animal lost its lunch millions of years ago — or why it upchucked in the first place — further analysis could determine other components of the partly digested animals that the predator swallowed.

"We think that there's more to this thing than just the tiny bones of amphibians," Foster said. "By doing a chemical analysis, we can begin to rule things out and determine what exactly the soft tissues are made up of."

Originally published on Live Science.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.