Glassified brain cells found in victim of Vesuvius eruption

The brain cells turned to glass after being exposed to an avalanche of hot ash.

Preserved brain cells have been found in the remains of a young man who died in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

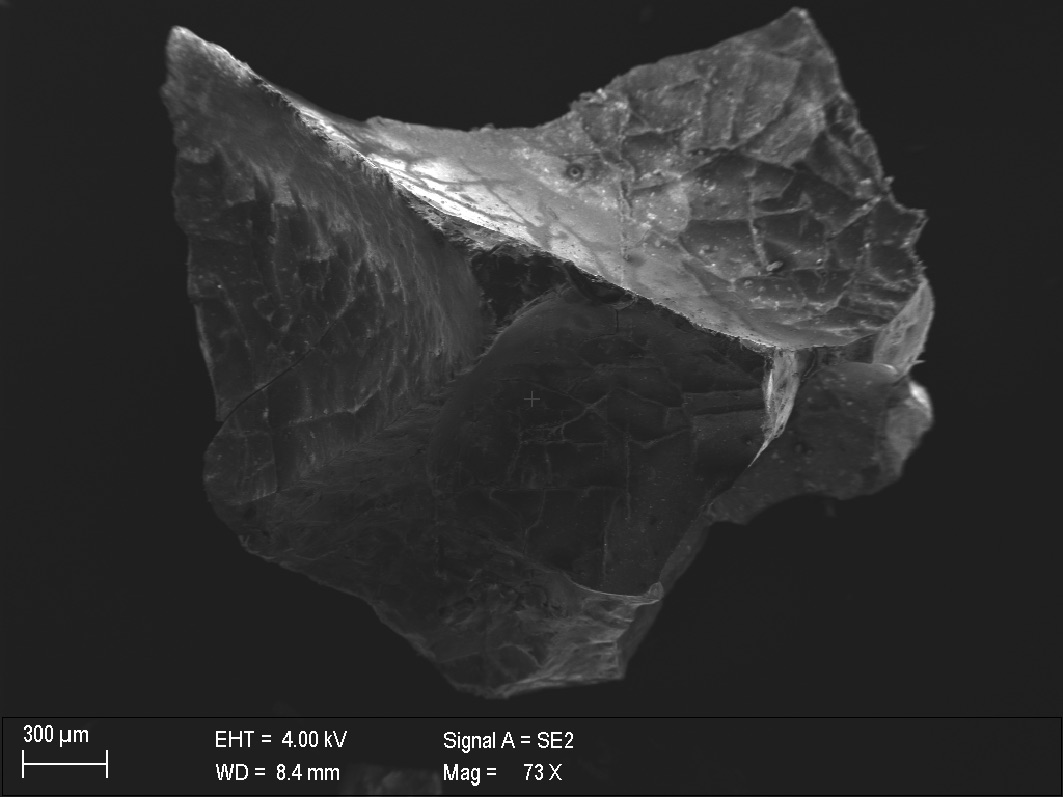

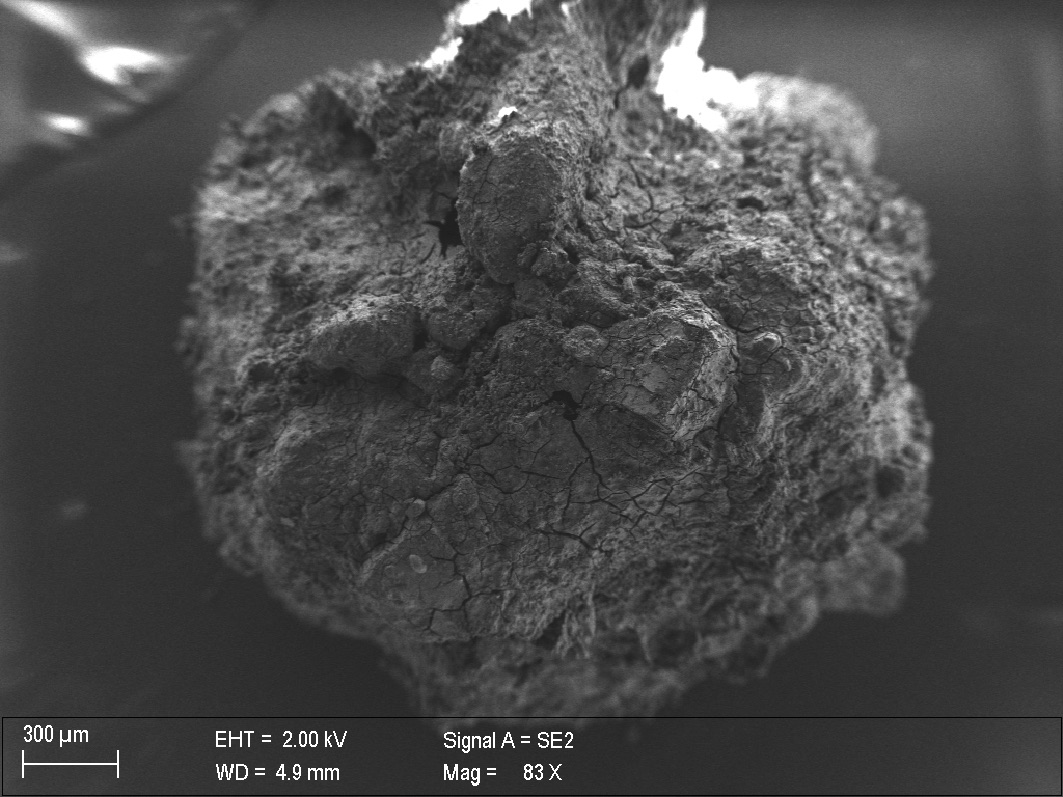

The brain cells' structure is still visible in a black, glassy material found in the man's skull. The new discovery of this structure, described today (Oct. 2) in the journal PLOS ONE, adds to the accumulating evidence that this glassy material is indeed part of the man's brain. The transformation to glass occurred as a result of extreme heating and rapid cooling.

"The results of our study show that the vitrification process occurred at Herculaneum, unique of its kind, has frozen the neuronal structures of this victim, preserving them intact until today," study lead author Pier Paolo Petrone, a forensic anthropologist at University Federico II of Naples in Italy, said in a statement.

Related: Photos: The bones of Mount Vesuvius

Herculaneum was an ancient town at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, which blew its top in a spectacular eruption nearly 2,000 years ago. A cloud of hot ash and gases, known as pyroclastic flow, buried Herculaneum as well as its famous neighbor, Pompeii.

This hot ash simultaneously destroyed and buried the town, rapidly heating organic materials. Strangely, though, the rapid burial meant that even though materials like wood and flesh were carbonized, or essentially turned to charcoal, they were also preserved as they were in the moments after being suddenly heated to 932 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius).

In rare cases, this preserved organic material seems to have included brains. Petrone and his colleagues examined a glassy black material found within the cracked and charred skull of a 20-something-year-old man found lying facedown on a bed in Herculaneum's Collegium Augustalium, or the College of the Augustales. This building, near Herculaneum's main street, was the headquarters of the cult of the Emperor Augustus, an organization that worshiped the emperor as a deity (a common Roman religious tradition at the time).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Petrone and his team have previously analyzed the remains of Herculaneum victims, suggesting that their body tissues may have vaporized in the cloud of hot ash; earlier this year, they reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) that they had found the glassy remains of a brain in the body of the 20-year-old from the Collegium Augustalium.

Now, using scanning electron microscopy to see the most miniscule details of the sample, the researchers have discovered tiny spherical structures and long tubular structures that look just like neurons and their projections, called axons.

At just 550 to 830 nanometers in diameter, these projections are too tiny to be capillaries. The spherical structures appear to retain cell membranes as well as internal filaments, or structural proteins inside the cell, and tiny vesicles, or internal sacs that help transport proteins to the cell surface.

The researchers also used a method called energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, which uses X-rays to determine the chemical makeup of a material. They found that the sample was rich in carbon and oxygen, indicating that it was organic. Building on the previous research published in JAMA, which detected a number of protein structures in the sample, the researchers compared these ancient proteins to a database of proteins found in the human brain. They found that all of the proteins they had discovered are present in brain tissue. For example, a protein called ATP6VIF is known to be involved in the transmission of chemicals known as neurotransmitters through synapses, the gaps between axons.

Based on the concentrations of these proteins and the position of the sample in the back of the skull, Petrone and his colleagues suspect they may have discovered part of the man's spinal cord and cerebellum, a brain structure at the base of the skull that is involved in movement and coordination.

Finding preserved brain tissue is rare in archaeology. But on occasion, brain tissue can survive for hundreds or thousands of years. For example, one 2,600-year-old skull found in a pit in Northern England contains the shrunken remains of a brain with some proteins still intact. Acidic chemicals from the surrounding clay may have halted decomposition in that case. Mammoth brains have also been found preserved in permafrost, thanks to extreme cold temperatures.

Originally published in Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.