Snake photos: Pythons swallow crocodiles and other animals … whole

Deer, crocodiles and even a human are just some of the odd meals engulfed by pythons. How do they gorge on such giant fare? Python snakes don't dislocate their jaws (a common myth), but instead rely on the springiness of the tissues connecting their jawbones.

Unlike in mammals, python snakes have a lower jawbone that is split into two parts that move independently of each other; and they are not connected by a bone in the front. In addition, the so-called quadrate bone that attaches the lower jaw to the skull is not rigidly attached in snakes, giving a python lots of wiggle room for devouring enormous prey.

"The two mandibles are not joined at the front by a rigid symphysis, as ours are, but by an elastic ligament that allows them to spread apart," Patrick Gregory, a biology professor at the University of Victoria in Australia, told Live Science previously. Here's a look at hungry snakes in action.

Pelican for breakfast

This African rock python (Python sebae) squeezed the life out of this white pelican in Kenya, before devouring the bird. Considered Africa's largest snake, these rock pythons can reach 20 feet (6 meters) in length and are known as powerful constrictors. In 2013, two boys were strangled to death by this snake in New Brunswick, Canada, National Geographic reported.

The snake has a stout, brown-gray body with two large, dark blobs running down its center, according to the Florida Museum.

A wallaby?

An oliver python (Liasis olivaceus), which is endemic to Australia and can grow up to 13 feet (4 m) long, just snagged the meal of the year: a wallaby. Like other pythons, this one used constriction to immobilize its prey, before gulping it down.

Go big, or ...

A wallaby? How about a crocodile? This olive python took down one of the giant reptiles near Mount Isa, Queensland, where kayaker Martin Muller captured the feat in all its gory glory on May 31, 2019. In addition to being able to fit enormous meals through their specialized jaws, pythons also have several adaptations to help the snakes digest such beasts all at once. For instance, researchers found that Burmese pythons modify their metabolism post-meal and even increase the size of internal organs — including intestines, pancreas, heart and kidneys — in order to process the huge caloric intake, Live Science previously reported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Too much to handle

A Burmese python in Florida met its match with a white-tailed deer that was supposed to be lunch for the hungry snake. In April 2015, biologists found the 11-foot-long (3 meters) Burmese python engorged with a tummy-full of deer at the Collier-Seminole State Park in Naples. Once the scientists, from the Conservancy of Southwest Florida (CSF), moved the snake to an open area, things got ugly. The python literally lost its lunch, regurgitating the prey, which turned out to be a fawn weighing some 36 pounds (16 kilograms); that was more than the arguably hefty snake, which tipped the scales at 32 pounds (14 kg). The incident was the largest prey-to-predator weight ratio ever reported in Burmese pythons, Live Science reported.

Peering beneath the skin

To learn more about how Burmese pythons shuttle their prey through their bellies, researchers put the giant snakes through scanners. They used magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography to scan fasting pythons before and after ingestion of a rat. The post-meal scans, at , 16, 24, 48, 72 and 132 hours after ingestion, showed a gradual disappearance of the rat's body and an overall expansion of the snake's intestine; meanwhile, the python's gallbladder shrunk and its heart increased in volume by 25%, Live Science reported at the time in 2011.

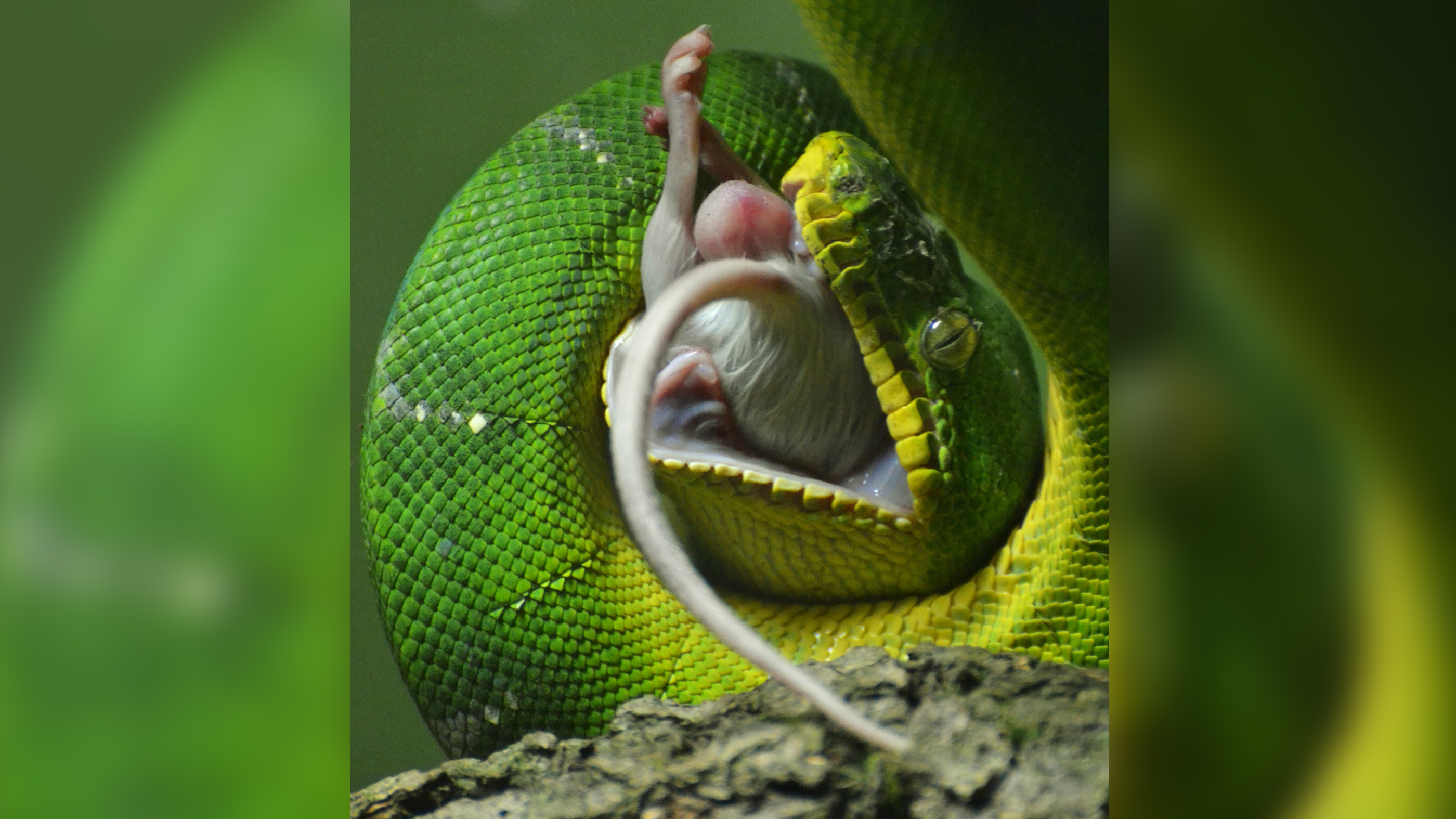

Head-first

A green tree python (Morelia viridis), which is native to New Guinea, consumes a mouse. The feasting snake is also sitting in its signature pose, with according to the Denver Zoo. "They coil their body around prey and each time the victim exhales, the snake tightens the coils eventually suffocating the prey animal. The snake then swallows the prey headfirst," the Denver Zoo said.

Oh, deer!

An Indian python swallowed a spotted dear in Yala National Park in Sri Lanka. Once a python has suffocated its prey, there's still work to do, as the snake must move its oversized meal through its body toward the digestive system. To do so, the python will open its mouth to begin swallowing the animal whole. It uses rhythmic muscular contractions of its body to pull the prey farther down its throat and into the stomach, according to the San Diego Zoo. And what about breathing? How did this Indian python continue to breathe while devouring a deer? Turns out, it has a special tube that stays open at the bottom of its mouth, the zoo explained.

Snake strangulation

Reticulated pythons (Malayopython reticulatus) are one of the world's largest snakes, according to Zoo Atlanta. And like other pythons, the giant reptile has several rows of sharp, S-shaped teeth that it uses to grab onto prey, like the mouse shown here, while coiling its might body tightly around the prey until all breathing ceases. In the wild, the reticulated python eats all kinds of birds and mammals, including large deer and boar, Zoo Atlanta said.

Backing in

In this close-up image of a hungry ball python (Python regius), you can see its lower jaw allows the mouth to stretch wide to fit a pudgy mouse, shown here in a zoo. In the wild in West and Central Africa, ball pythons rely on such rodents for survival. To catch their prey, ball pythons tend to pull back the head and neck before rapidly striking their meals. Next, the ball python either just swallows the prey or first immobilizes it with strangulation, according to the Animal Diversity Web (ADW), supported by the University of Michigan.

They get their name from their "balling" behavior, in which they form a tight ball with their bodies — with the head at the center — to protect themselves when threatened, ADW explained.

That's a big rat

Though the Australian black-headed python (Aspidites melanocephalus) primarily eats other reptiles, mainly skinks, this individual took down a black rate (Rattus rattus). The python calls northern parts of Australia home, where it slithers through dry scrublands, savannas and damp forests, according to the University of Michigan's Animal Diversity Web.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.