Of the 10 biggest annual meteor showers, just two could produce over 100 per hour: the December Geminids and the January Quadrantids, due to peak Monday (Jan. 3).

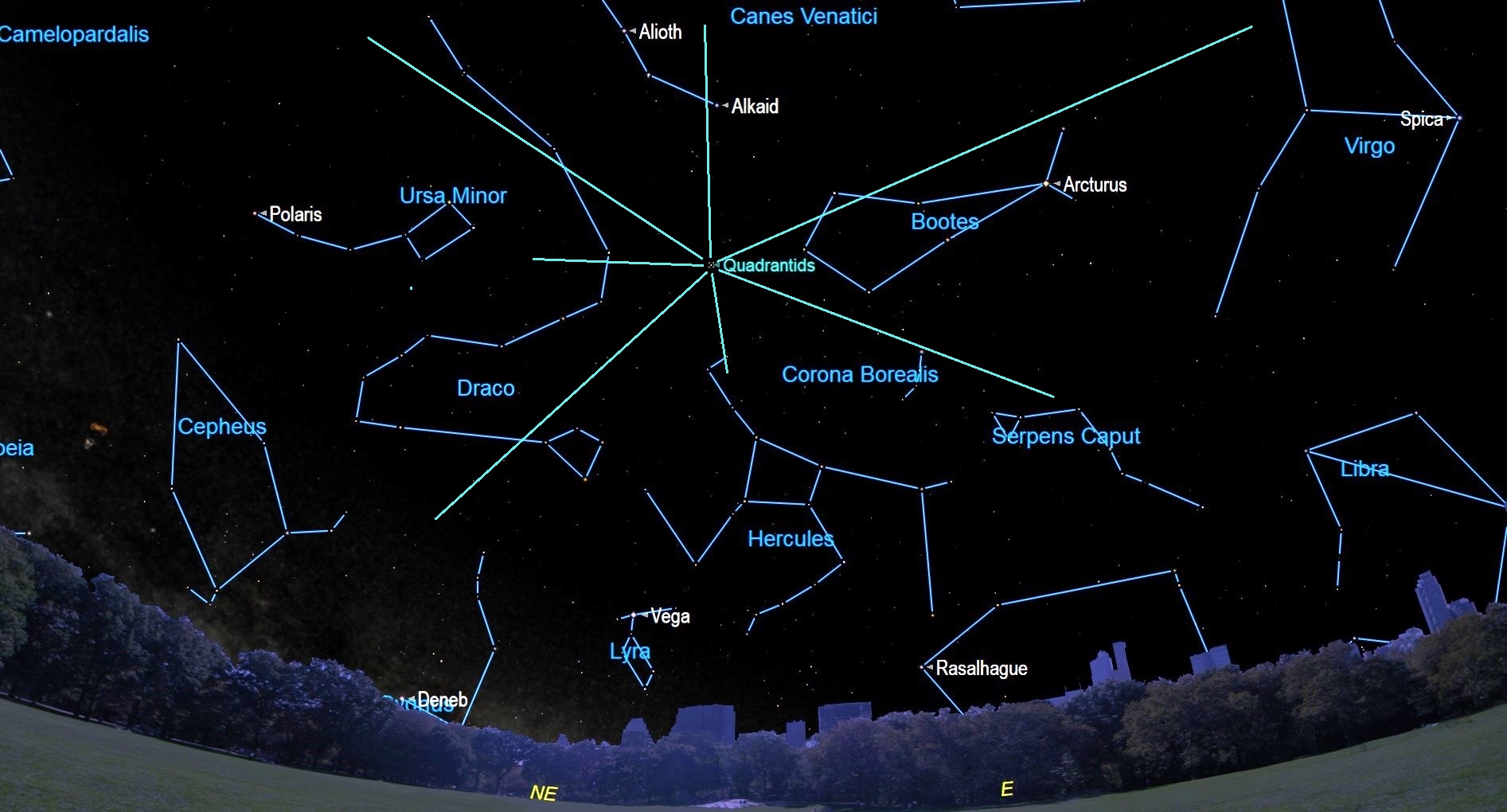

Every year, Earth briefly encounters the Quadrantid meteor shower in early January. Using constellations as a guide, Quadrantid meteors, or "Quads," appear to fan out from a spot in the night sky midway between the Big Dipper's handle and the four stars marking the head of Draco, the dragon.

The main challenge in spotting the Quadrantids is catching them when they are active because they are a very short-lived display. The Quadrantids characteristically spend only about 12 hours rising from quarter-strength to peak activity and their subsequent decline can take as little as 4 hours. Also, from different hemispheres on Earth, skywatchers report seeing the Quadrantids in dramatically different numbers.

Related: Quadrantid Meteor Shower: Odd in Several Ways

Good and bad in 2022

There is good news and bad news for this year’s Quadrantid meteor show.

First, the good news: the new moon arrives on Jan. 2, so there will be no bright moonlight to hinder visibility.

Now, the bad news (for some):

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

According to Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown in the 2022 edition of the "Observer's Handbook" of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (as found on page 254), the "Quads," as they are nicknamed, are due to peak this year at around 04:00 p.m. EDT (2100 GMT) on Mon. Jan. 3. That’s excellent timing if you live in East Asia where skywatchers in ideal conditions could expect to see up to 60 to 120 meteors per hour.

But for skywatchers in North America, you'll be facing the "wrong way" when this shower reaches its peak. The shower peaks in the mid-afternoon during the bright sunny daytime. That means that many skywatchers will have essentially no chance of seeing meteors streaking across the sky during the shower's peak.

Related: Quadrantid Meteor Shower Wows Stargazers

Best views on Monday morning

While the timing of the shower's peak isn't great for many skywatchers, there are certainly other times during which you might spot some "shooting stars."

For those in North America missing the spectacle during its peak, your best chance at catching some Quadrantid activity will come during the predawn hours of Monday morning. After about 3 a.m. EDT (0800 GMT), the radiant or emanation point for these meteors will be climbing well up into the northeast; it's highest before dawn.

The shower will be building toward its peak later that day, but you still might glimpse as many as 15 to possibly 30 meteors per hour. While this isn't the onslaught of bright meteor streaks that observers in East Asia might see, it's still enough meteor activity to be entertaining and to perhaps lure you outside during the (very) early morning hours.

The Quads "rock"

Just like December's Geminids meteor shower, the Quadrantids are cosmic debris shed not by a comet, but a near-Earth asteroid. In this case, the shower is made up of bits of the asteroid 2004 EH1 burning up in Earth's atmosphere.

It is hypothesized that at one time in the far-distant past, this asteroid was an active comet that somehow still sheds meteoric material out into space. Like the Geminids, the meteors that appear after the shower's peak tend to be brighter than the earlier ones, indicating that the larger particles are on the outer side of this meteoroid stream. These meteors have been described as traveling at a medium speed and being reasonably bright and usually blue in color. But only a few, maybe just 5 to 10 percent, also leave fine, long-spreading and persistent silver trails in their wake.

The meteors' unusual moniker also has a history. There was at one time a dim, shapeless star pattern known as Quadrans Muralis, the "wall quadrant." The pattern was pictured on many 18th- and 19th-century star atlases and was created by French astronomer Jérôme Lalande from a scattering of dim stars between the constellations of Draco and Boötes. The instrument it was supposed to portray was used to measure the altitudes of celestial objects, but never caught on and ultimately the star pattern became defunct.

And a final note (or is it a reminder?) — it's January, the coldest month of the year. So, if you plan to hunt for some Quads, remember to bundle up warmly!

Good luck and clear skies!

Editor's note: If you have an amazing skywatching photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, you can send images and comments in to spacephotos@space.com.

Night Sky Guides:

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook