Ancient turtle with a frog face sucked down its prey millions of years ago

It has been named the "quick-mouthed frog turtle."

Paleontologists in Madagascar recently discovered an exceptionally well-preserved fossil of a new and extinct species of turtle, dating back to the late Cretaceous Period, which began around 100 million years ago. The newly discovered species would have had a frog-like face and eaten by sucking in mouthfuls of prey-filled water.

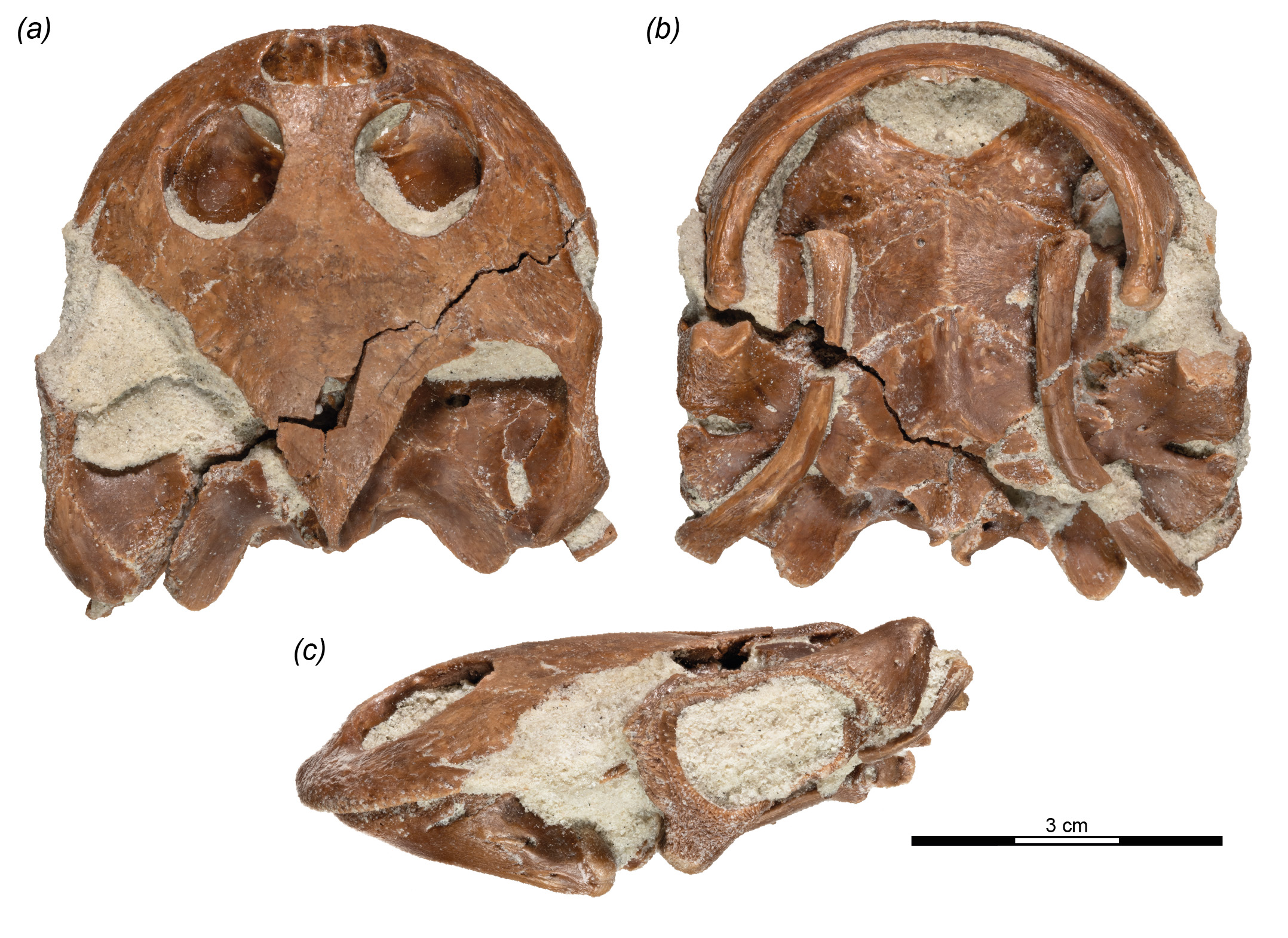

The ancient turtle was a freshwater species endemic to Madagascar, with a shell length of around 10 inches (25 centimeters). It had a flattened skull, rounded mouth and large tongue bones, all of which would have made it a great suction feeder and given it an amphibian-like appearance. In a new study describing the species, the researchers named it Sahonachelys mailakavava, which means "quick-mouthed frog turtle" in Malagasy, the language spoken by Indiginous people of Madagascar.

Researchers unearthed the turtle's fossil in 2015 while searching for the remains of dinosaurs and crocodiles at a site on the island with a history of such finds. While removing the overburden — the typically bare layers of sediment above fossil-rich layers — the team was surprised to find bone fragments from a turtle's shell and eventually recovered an almost intact skeleton.

Related: Sea science: 7 bizarre facts about the ocean

"The specimen is absolutely beautiful and certainly one of the best-preserved late Cretaceous turtles known from all southern continents," lead author Walter Joyce, a paleontologist at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, told Live Science. "In all regards, this is an exceptionally rare find."

The researchers are unsure how far back the quick-mouthed frog turtle may have emerged or when and why it went extinct; but the new species "likely survived the big extinction event that killed the dinosaurs" and brought the Cretaceous Period to an end around 66 million years ago, Joyce said.

Suction feeders

Quick-mouthed frog turtles were most likely suction feeders, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is a specialized mode of underwater feeding, during which the animal quickly opens its mouth and expands its throat to quasi-inhale a large volume of water, including the desired prey item," which would have included plankton, tadpoles and fish larvae, Joyce said.

Its flattened skull, mouth shape and delicate jaws are all telltale signs that this turtle used suction for feeding. "Suction feeders need to quickly create a large circular opening through which they suck water," Joyce said. "As the prey items are transported directly into the esophagus, suction feeders do not have strong jaws, as they do not bite."

The turtle also had enlarged tongue bones for its size, which suggests it had strong muscles to allow the quick expansion of its throat, Joyce said.

Convergent evolution

The quick-mouthed frog turtles belonged to the Pelomedusoidea family, which includes living species such as South American and Madagascan river turtles. "Although the group is not particularly diverse today, its fossil record shows that the group nearly conquered all landmasses in the past and was much more diverse," Joyce said.

The quick-mouthed frog turtle was "likely the first Pelomedusoid" to have evolved as a suction feeder "to such an extreme," Joyce said. There are several modern-day turtle species that suction feed, most of which belong to the family Chelidae and evolved separately from the quick-mouthed frog turtle.

When Joyce first saw the skull, he thought it belonged to a Chelid, he said. "The shell, however, clearly showed that it is a Pelomedusoid." This is evidence of convergent evolution and means Chelids and Pelomedusoids, which are distantly related, have each evolved this ability independently of one another, Joyce said.

"It highlights that distantly related animals will converge upon the same shape when adapting to similar lifestyles," Joyce said.

The study was published online May 5 in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.