'Truly remarkable' fossils are rare evidence of ancient shark-on-shark attacks

These fossils are rare because shark cartilage seldom fossilizes.

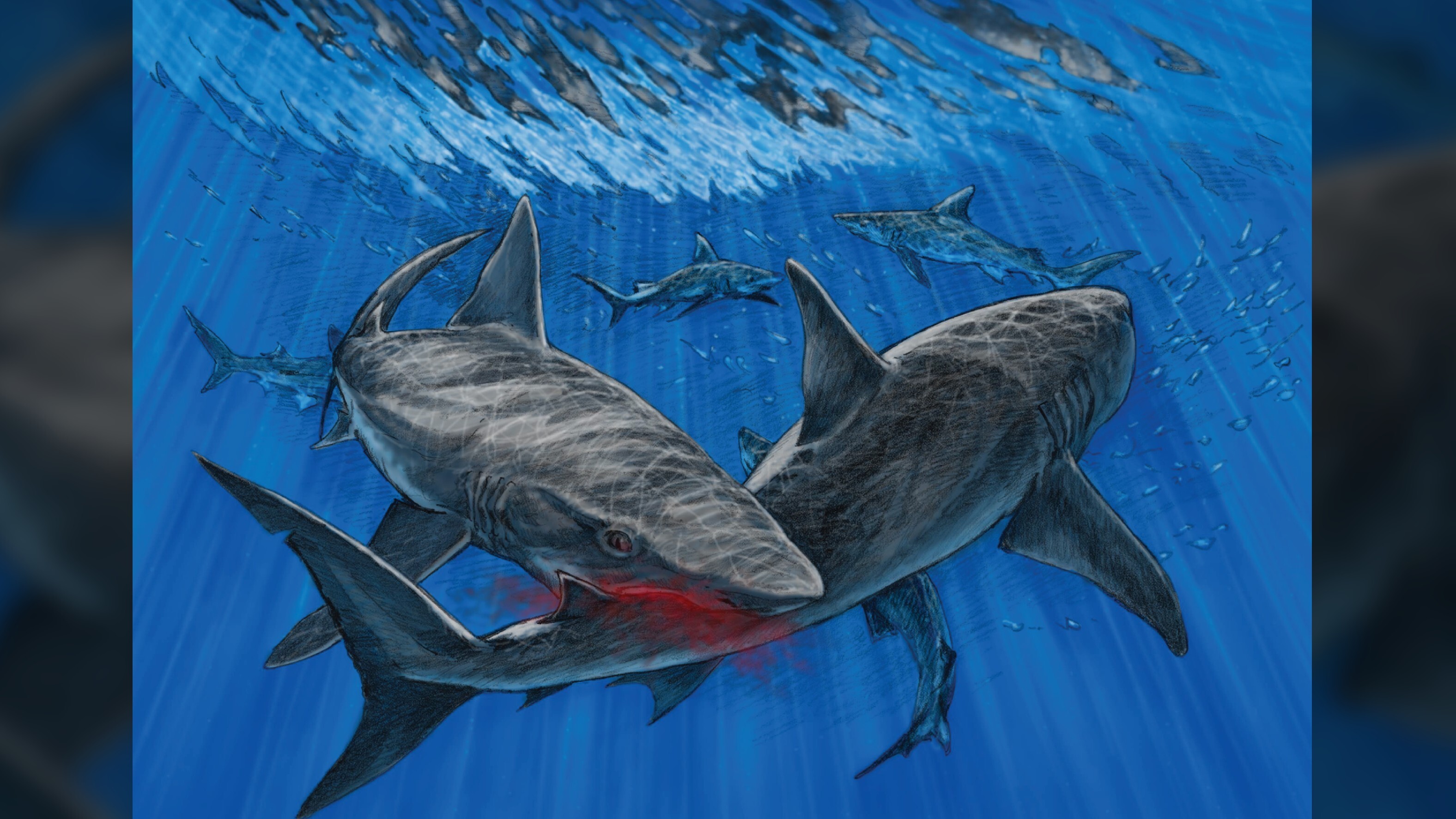

During the age of megalodon, sharks hunted all kinds of creatures, including other sharks, according to a new study based on four rare fossils.

In four separate finds, researchers and amateur fossil hunters discovered the ancient vertebrae of now-extinct sharks; all four vertebrae are covered in shark bite marks, and two still have pointy shark teeth sticking out of them. These findings are extraordinary, as shark skeletons are made of cartilage, which doesn't fossilize well, the researchers said.

The discoveries show that millions of years ago, ancient sharks gobbled up fellow sharks off what is now the U.S. East Coast. "Sharks have been preying upon each other for millions of years, yet these interactions are rarely reported due to the poor preservation potential of cartilage," study co-researcher Victor Perez, an assistant curator of paleontology at the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons, Maryland, told Live Science in an email.

Related: 7 unanswered questions about sharks

Researchers have known for decades about shark-on-shark predation and even cannibalism. It's a behavior seen in living sharks, including many lamniformes — an iconic group that includes goblin, megamouth, basking, mako and great white sharks — which, as fetuses, sometimes devour their siblings in the womb, the researchers said.

Ancient sharks have left their bite marks on countless paleo beasts, including on the bones of marine mammals, ray-finned fishes and reptiles — even pterosaurs, flying reptiles that lived during the dinosaur age, two studies found. However, evidence of ancient shark-versus-shark attacks is somewhat rare. The oldest evidence of shark-on-shark predation dates to the Devonian period (419.2 million to 358.9 million years ago), when the shark Cladoselache gulped down another shark, whose remains were fossilized in its gut contents.

In the new study, researchers examined three shark fossils found at Calvert Cliffs on the Maryland coast between 2002 and 2016, and a fourth discovered in a phosphate mine in North Carolina in the 1980s. All of the fossils date to the Neogene period (23.03 million to 2.58 million years ago), a time when megalodon (Otodus megalodon), the world's largest shark on record, stalked the seas. (However, megalodon wasn't involved in these four attacks.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unlike sturdy bone, shark cartilage is a soft tissue made of tiny hexagonal prisms, which rapidly break apart after the animal dies, Perez said. "So, to find cartilaginous elements of a shark's skeleton is already rare, but to find these skeletal elements with bite traces is truly remarkable," he said. "There needs to be exceptional circumstances for this predatory interaction to preserve for millions of years and to be recovered by someone who recognizes its significance."

So, how did these four fossils survive? All are centra, or the vertebrae that make up the spinal column. "The centra are composed of a denser calcified cartilage that preserves better than other parts of the skeleton," Perez noted. In fact, these four fossils are the first documented ancient shark centra with shark bite marks on them, the research team said.

It's unclear whether these bites — known as trace fossils, which are fossilized remnants from animals that are not parts of their bodies, like footprints, bite marks or even poop — were made during an active attack or a scavenging event, Perez said. At least one, however, may have come from an attack; one fossil from Maryland that still had two, nearly 1.5-inch-long (4 centimeters) teeth sticking out of it shows signs of healing, indicating that the shark survived the encounter.

A bone analysis revealed the victims were chondrichthyans, a class with 282 species alive today, including bull sharks, tiger sharks and hammerhead sharks. "We cannot identify the exact species involved in these encounters, but we can narrow it down to some likely culprits," Perez said.

Based on its shape, the fossil with two embedded shark teeth belongs to the family Carcharhinidae, in one of two genera: Carcharhinus or Negaprion, the researchers said. The embedded teeth may also be from a Carcharhinus or Negaprion shark, the researchers found.

Another Maryland specimen, which also appears to be from the family Carcharhinidae, had bite marks from several attackers — possibly chondrichthyan sharks, lamnid sharks or bony fish. The third Maryland specimen might belong to the Galeocerdo genus, whose only surviving species is the tiger shark (G. cuvier).

The embedded teeth and a gouge mark on the specimens, "suggest that these centra were all bitten very forcefully," the researchers wrote in the study.

Two of the specimens are now on display at the Calvert Marine Museum in the new exhibit "Sharks! Sink your teeth in!" The study was published online Dec. 7, 2021, in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.