Ancient Egyptian 'masterpiece' is so realistic, researchers identified the exact bird species it depicts

An ancient Egyptian painting is so detailed, researchers can determine which species of birds were featured in it.

An ancient Egyptian "masterpiece" painting of birds flying and perching within a verdant marsh is so detailed, modern researchers can tell exactly which species artisans illustrated more than 3,300 years ago.

The painting was discovered about a century ago on the walls of the palace at Amarna, an ancient Egyptian capital located about 186 miles (300 kilometers) south of Cairo. Although previous research has examined the mural's wildlife, the new study is the first to take a deep dive into the identity of all of the birds, some of which have unnatural markings.

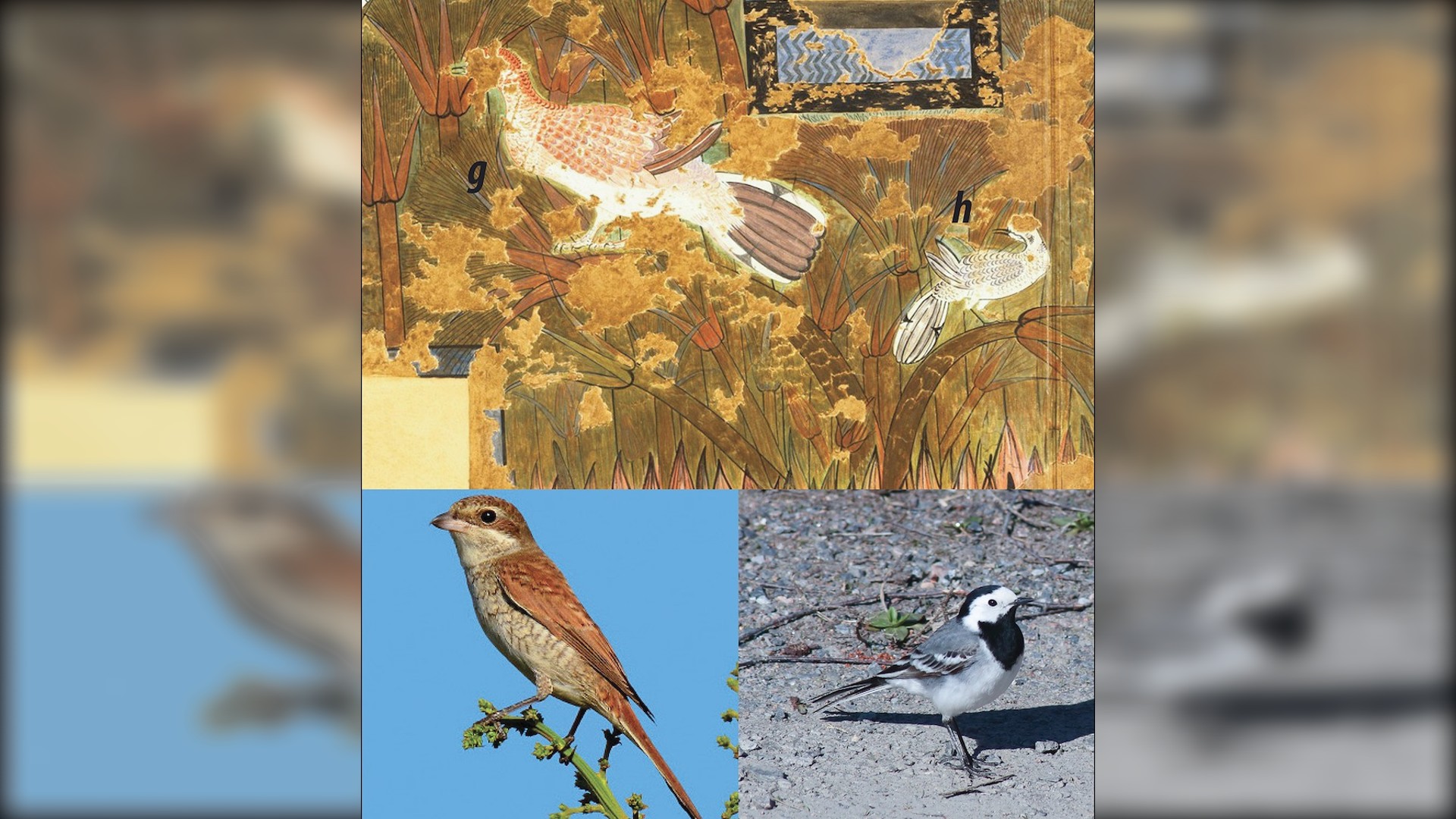

Many of the birds depicted are rock pigeons (Columba livia), but there are also images showing a pied kingfisher (Ceryle rudis), a red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio) and a white wagtail (Motacilla alba), study co-researcher Christopher Stimpson, an honorary associate at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and study co-author Barry Kemp, professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge, wrote in a study published Dec. 15 in the journal Antiquity. The team studied a facsimile (a copy) of the artwork and used previously published ornithological and taxonomic research papers to identify the birds.

The room, which today is known as the "Green Room," is painted with images of water lilies, papyrus plants and birds — a scene that may have created a serene atmosphere where the royal family could relax, the researchers said. It is "realistic to suggest that the calming effects of the natural environment were as important to the royal household then as it has increasingly been shown to be today," Stimpson and Kemp wrote in the study.

It's possible that real plants were kept in their room along with perfume and that ancient Egyptians played music there. "A room adorned with, by any measure, a masterpiece of naturalistic art, and filled with music and perfumed by cut plants, would have made for a remarkable sensory experience," the researchers wrote.

Related: Ancient mummy portraits and rare Isis-Aphrodite idol discovered in Egypt

Green Room

Between roughly 1353 B.C. and 1336 B.C., the pharaoh Akhenaten (the father of King Tutankhamun) ruled Egypt. He changed Egypt's religion, focusing it around the worship of the Aten, the sun disk. He built a new capital called Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna) and had the north palace constructed in it.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Excavated between 1923 and 1925 by the Egypt Exploration Society, the paintings in the Green Room were fragile, and Egyptologist Nina de Garis Davies painted facsimiles of them. The facsimiles are important because the paintings no longer exist.

"The only way to have preserved them would have been to rebury the rooms in sand," Kemp told Live Science in an email. "The archaeologists chose not to do this, fearing that local people would have damaged them, a fear that was probably exaggerated."

In 1926, an attempt to conserve the panels with consolidants (a substance meant to strengthen it), backfired, and made the paintings discolored and darkened, the researchers wrote in their paper. This meant that the researchers had to rely on facsimiles drawn by de Garis Davies to identify the birds.

While the pied kingfisher and rock pigeons can still be found in Egypt year-round, the red-backed shrike and white wagtail are migratory birds, the researchers wrote. "Red-backed shrikes are common autumn migrants in Egypt between August and November," while the white wagtail is a "common passage migrant from October to April," when it is an abundant winter visitor in cultivated areas where crops grow, the researchers wrote.

The masterpiece shows a number of rock pigeons, even though these birds are not native to Egypt's papyrus marshes; instead, these birds are associated with the region's desert cliffs. The researchers say that the likeliest explanation is that the ancient artists decided to include them anyway to make the scene look better. "Their presence may have been a simple motif to enhance a sense of a wilder, untamed nature," the researchers wrote.

Curiously, the ancient artists marked the red-backed shrikes and white wagtails with triangular tail markings that the birds don't have in real life. The researchers speculated that the artists may have drawn these markings to indicate that both bird species visited Egypt only seasonally.

Despite these markings, the artists did a good job of creating realistic images of birds and plants. "I think the Green Room images are remarkable, even in the wider context of ancient Egyptian art, as an example of the close observation of the natural world," Stimpson told Live Science in an email.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.