Dinosaur 'reaper' with massive claws found in Japan

The herbivore used its vicious-looking claws to forage for food.

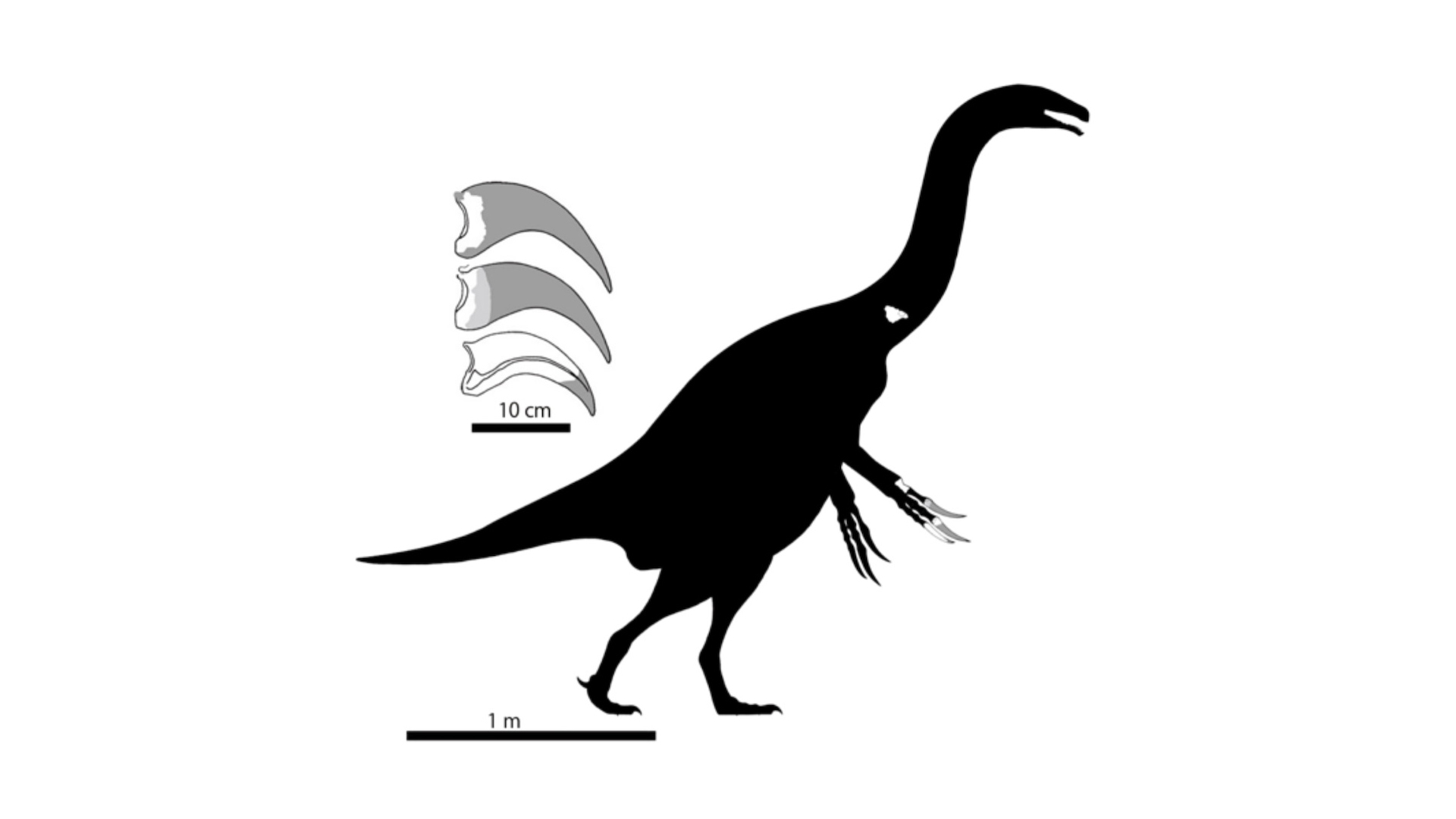

Millions of years ago, a bipedal dinosaur with knives for fingers stalked the shores of the Asian continent. But those Edward Scissorhandslike weapons were used for slashing vegetation rather than eviscerating animal prey, according to a new study.

The dinosaur belonged to a group known as therizinosaurs — bipedal and primarily herbivorous three-toed dinosaurs that lived during the Cretaceous period, about 145 million to 66 million years ago. Recently, researchers from Japan and the United States described the youngest therizinosaur fossil ever found in Japan; that fossil also happens to be the first to be found in Asia in marine sediments.

This fossil represents a newly described species, which the researchers named Paralitherizinosaurus japonicus. The genus, which was already known to science, means "reptile by the sea" in Greek and Latin; the species name honors Japan, where the specimen was unearthed.

The hook-shaped fossil, which includes a partial vertebra and a partial wrist and forefoot, was discovered by a different team of researchers in 2008; since then, it was stored in the collections at the Nakagawa Museum of Natural History in Hokkaido, Japan.

Japanese scientists found the specimen in Nakagawa, a district in Hokkaido located on the northernmost of Japan's main islands, a locale known for its rich fossil deposits. The fossil was encased in a concretion — a hardened mineral deposit — and at the time of its discovery, paleontologists said it "was believed to belong to a therizinosaur," though due to a lack of comparative data at the time, the original researchers were unable to draw any definitive conclusions, representatives of Hokkaido University said in a statement.

Related: How did 'Prehistoric Planet' create such incredible dinosaurs? Find out in a behind-the-scenes peek.

However, new data from many other fossils that were discovered and described in the years since have helped with classifying the fossil based on the shape of the forefoot claw. This prompted a new team of paleontologists to revisit the specimen to get some definitive answers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on their analysis, the authors of the new study concluded that the fossil, which measures just under 4 inches (10 centimeters) in length, belonged to a therizinosaur that lived approximately 80 million to 82 million years ago. The fossilized foot bone once held the dinosaur's swordlike claw, which it used for combing through vegetation for plants to eat. Because researchers suspect that the animal used its claws for a specific purpose, they determined that the specimen was a derived therizinosaur — one that evolved later in the group's lineage — rather than a basal, or early therizinosaur, with claws that were "generalized and not for specific use," according to the statement.

"[This dinosaur] used its claws as foraging tools, rather than tools of aggression, to draw shrubs and trees closer to its mouth to eat," study co-author Anthony Fiorillo, a research professor in the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences at Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas, told Live Science. "We believe it died on land and was washed out to sea."

According to the study, therizinosaur fossils have been found throughout Asia as well as in North America (specifically in what is now Denali National Park and Preserve in Alaska), and that, over time, the animals adapted to living in coastal environments. Two more suspected therizinosaur fossils were previously discovered in Japan, but have not yet been described.

Based on this specimen alone, it's impossible to know for sure how large the therizinosaur was, Fiorillo told Live Science. What scientists can say with certainty is that the dinosaur was "sizable," possibly as large as a hadrosaur, or duck-billed dinosaur, which could grow to be 30 feet long (9 meters) and weigh up to 3 tons (2.7 metric tons), according to the University of California Museum of Paleontology. The fossil is so well-preserved, "we could find more of the animal if we revisited the original site," Fiorillo said.

"We remain cautiously optimistic, and it's on our radar,"" added Fiorillo, who is also a curator emeritus at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas.

The findings were published online May 3 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Originally published on Live Science

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.