6 Reasons Astrobiologists Are Holding Out Hope for Life on Mars

Astrobiologists want to believe.

Introduction

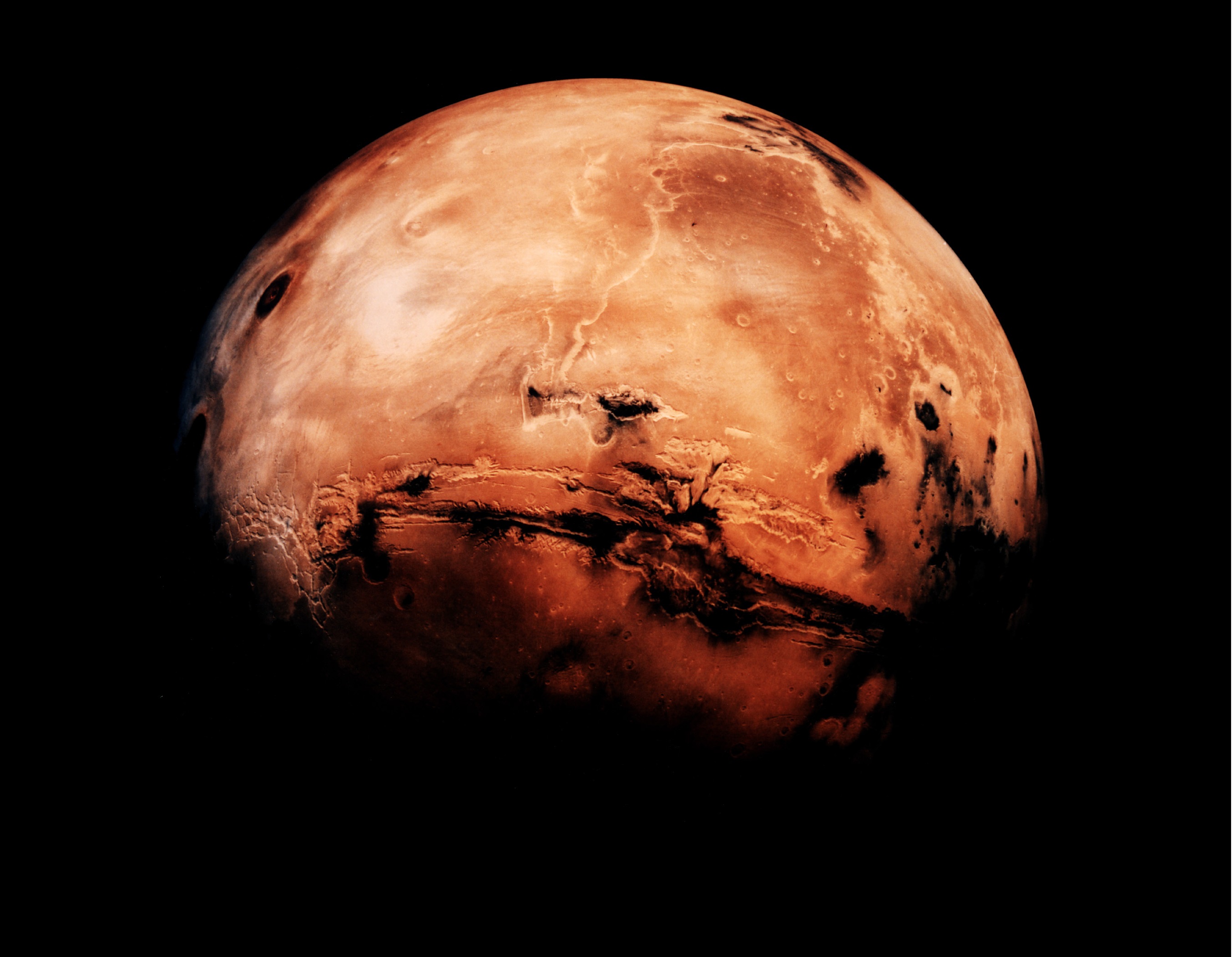

Mars may seem barren and inhospitable today, but long ago the Red Planet once looked very different. Once upon a time, Mars was warmer than it is now, and covered in rivers, lakes and seas. There's no way of saying for sure whether Martians ever existed, experts say. Still, there's mounting evidence that Mars was not only habitable in theory, but actually home to some kind of extraterrestrial life. It's even possible that remnants of that life still lurk undiscovered beneath Mars' surface. Here are six reasons why astrobiologists believe in the possibility of life on Mars.

River valleys and deltas: Mars' incredible geography

The Martian landscape puts Earth to shame. Its tallest peak, Olympus Mons, towers 85,000 feet (26,000 meters) above the plain surrounding it, according to the European Space Agency. That's three times taller than Mount Everest. Wide riverbeds snake across the Martian landscape and fan out into deltas. Some of these geological formations can be explained by ancient volcanic activity or Mars' fierce winds, James W. Head, a geologist at Brown University, wrote in "The Geology of Mars: Evidence from Earth-Based Analogs" (Cambridge University Press, 2007). But others are clearly relics of ancient bodies of water. For instance, apparent riverbeds on Mars tend to end in large craters, the bottoms of which appear flattened. That's a sign that ancient rivers were depositing sediment there — and that the Martian landscape was once dominated by rivers, lakes and seas.

But the modern consensus that ancient Mars was wet raises an important question: What happened to all that water?

Related: 9 Strange, Scientific Excuses for Why Humans Haven't Found Aliens Yet

Traces of water

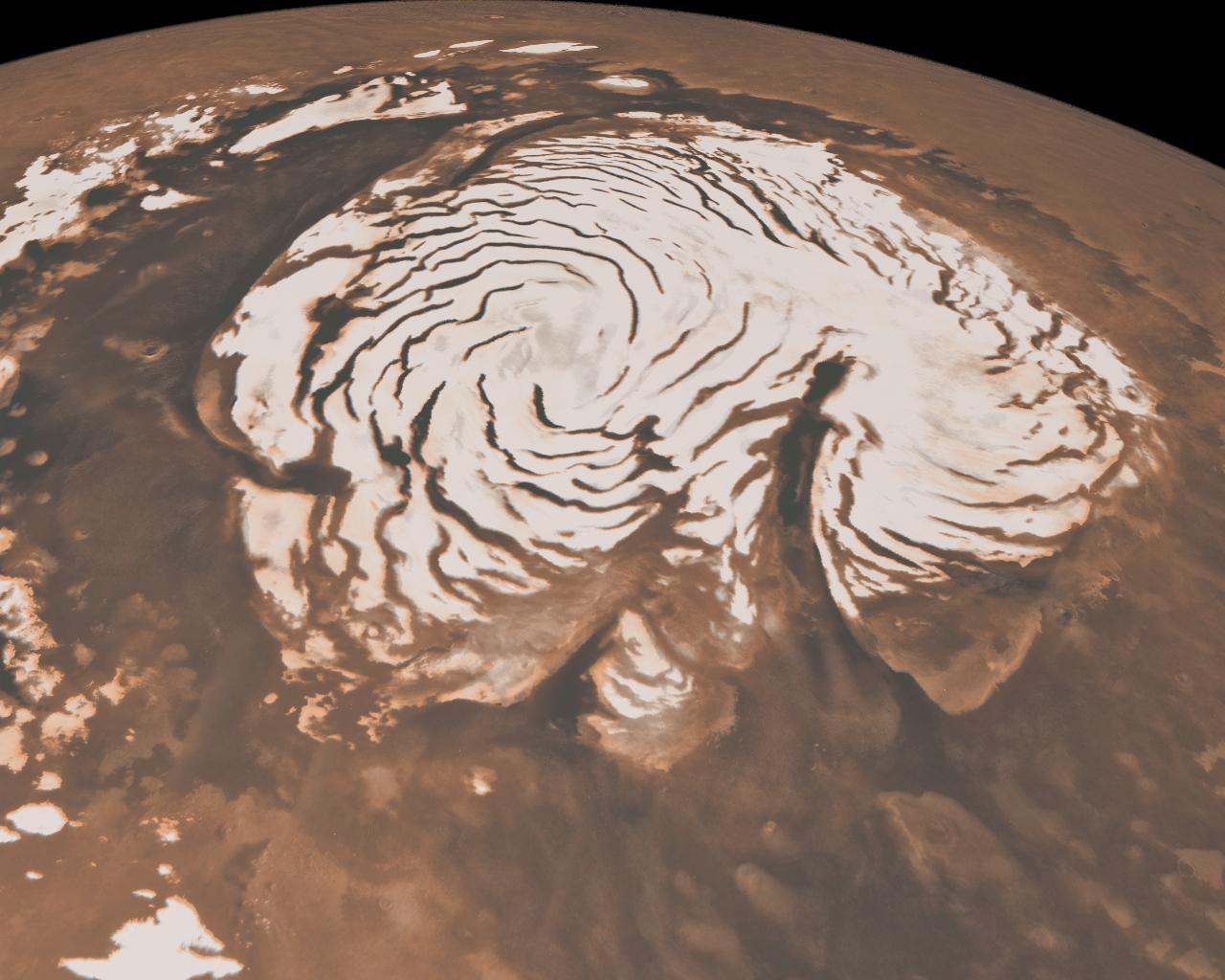

If you were to pour a bottle of water onto the surface of Mars, the water would boil away before it hit the planet's surface. That's not because the Red Planet is hot — nighttime temperatures sometimes hit minus 225 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 142 degrees Celsius). Water boils because the Martian atmosphere is incredibly thin. The air pressure is so low that there's nothing to hold water molecules in place, even at freezing temperatures. Today, water exists on Mars in only one form: ice, hidden under the surface at the two poles of the planet.

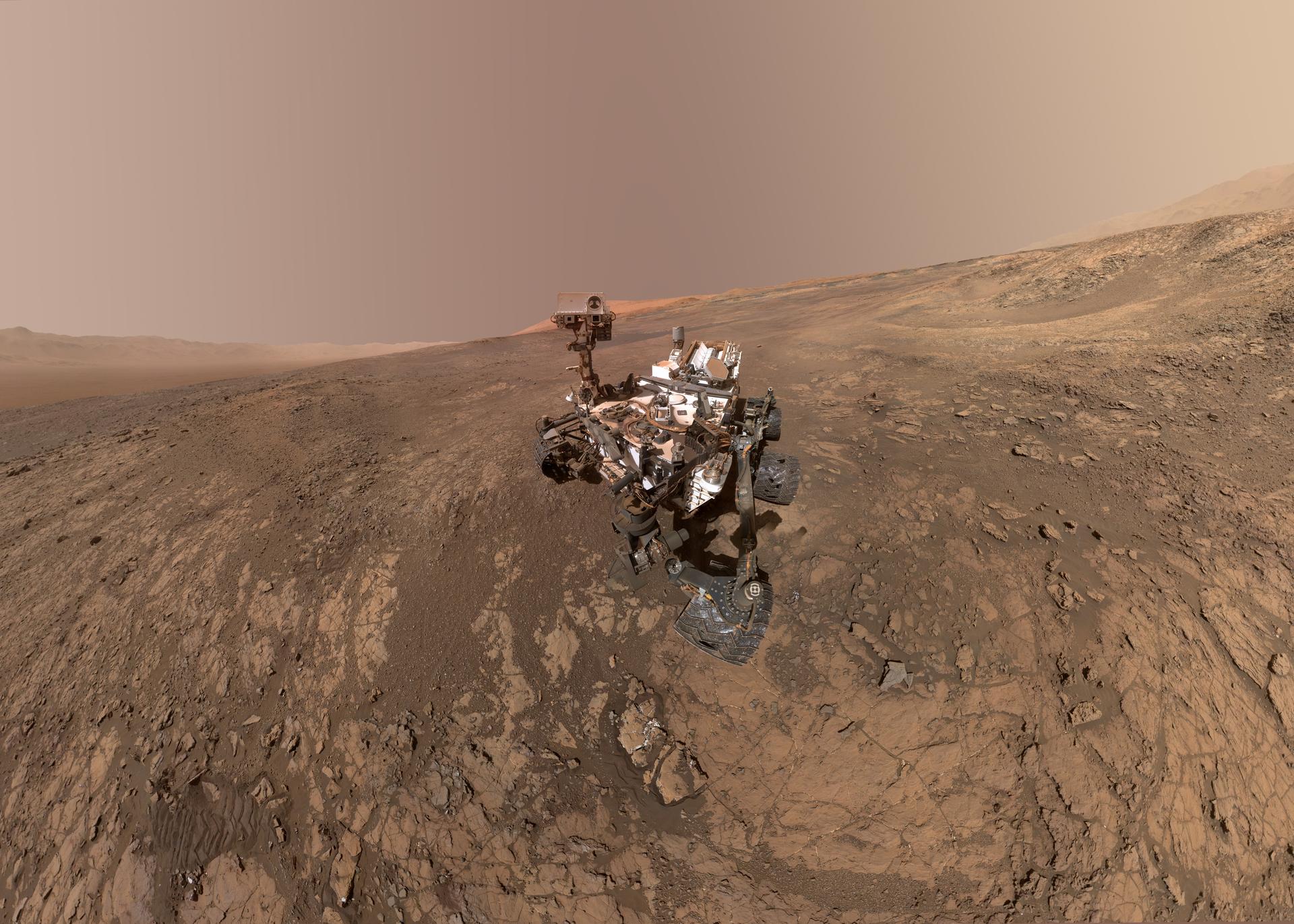

But Mars clearly wasn't always this inhospitable to life. Rovers on Mars, including Curiosity, have found chemical evidence of liquid water: large deposits of clay molecules, according to NASA. Clay molecules are generally only formed when water is present — to scientists, that's a clear indicator that Mars was most likely much warmer, with a thick enough atmosphere to sustain liquid.

Water may be a requirement for life on Earth, but it isn't a guarantee that life once existed on Mars, Penelope Boston, an astrobiologist at NASA, told Live Science. That said, this piece of evidence does take us one step toward the conclusion that life was once possible on the Red Planet.

"There's no single silver bullet on this life-detection issue," Boston said. "The data is cumulative."

So water is just one piece of data among many pointing to the conclusion that life could have existed on Mars — and perhaps still does.

On Earth, carbon and hydrogen are everywhere. In fact, 75% of your body (excluding water) is composed of these two elements.They make up everything from our DNA to our cell walls. We call these chemicals "organic" — and life as we know it on Earth wouldn't exist without them.

So in 1984, when scientists found a Martian meteorite in Antarctica crawling with organic chemicals, their discovery raised an interesting question: Did the organic chemicals come from life?

At first, scientists speculated that these chemicals could have been introduced to the meteorite after impact. However, the chemical signatures of the organic material weren't concentrated on the surface of the rock, as you would expect if it had picked them up later. Instead, the organic compounds grew denser and denser toward the center of the meteorite.

Still, scientists were skeptical that they would ever find organic chemicals on Mars. The surface of the atmosphere-less planet is just too harsh to even sustain organic chemical structures, they speculated. However, more recently, Mars rovers like Curiosity have discovered clear traces of organic compounds on the planet's surface. In 2012, Curiosity found chemicals similar to kerogen, a component of fossil fuel.

Life is an important source of organic compounds — but not the only one. Geological processes can also result in the creation of organic compounds, Boston said. For example, volcanoes sometimes spew organic compounds into the atmosphere. So while it's possible that the chemicals are a sign of past life, it's still not certain.

Earlier this year, Curiosity uncovered another potential sign of life on Mars — a record high measurement of a natural gas called methane. On Earth, methane comes primarily from microbes. So while the Martian reading of 21 parts per billion (ppb) was relatively low (for perspective, concentrations on Earth are close to 1,860 ppb), the plume is still a promising sign that life once existed — or still exists unseen — on the Red Planet. And this wasn't the first time Curiosity detected methane on Mars. On average, methane concentrations hover at around 7 parts per billion (ppb) and vary seasonally — rising in the summer and falling in the winter. This seasonal pattern is another clue to the source of the methane. Beneath the Martian surface lies a layer of ice. Perhaps in summer, this ice thaws, releasing pockets of trapped methane. While reactions between rocks and ice can create methane, according to NASA, it's possible these methane bubbles come from underground life — ancient or existing.

Related: The 10 Strangest Places Where Life Is Found on Earth

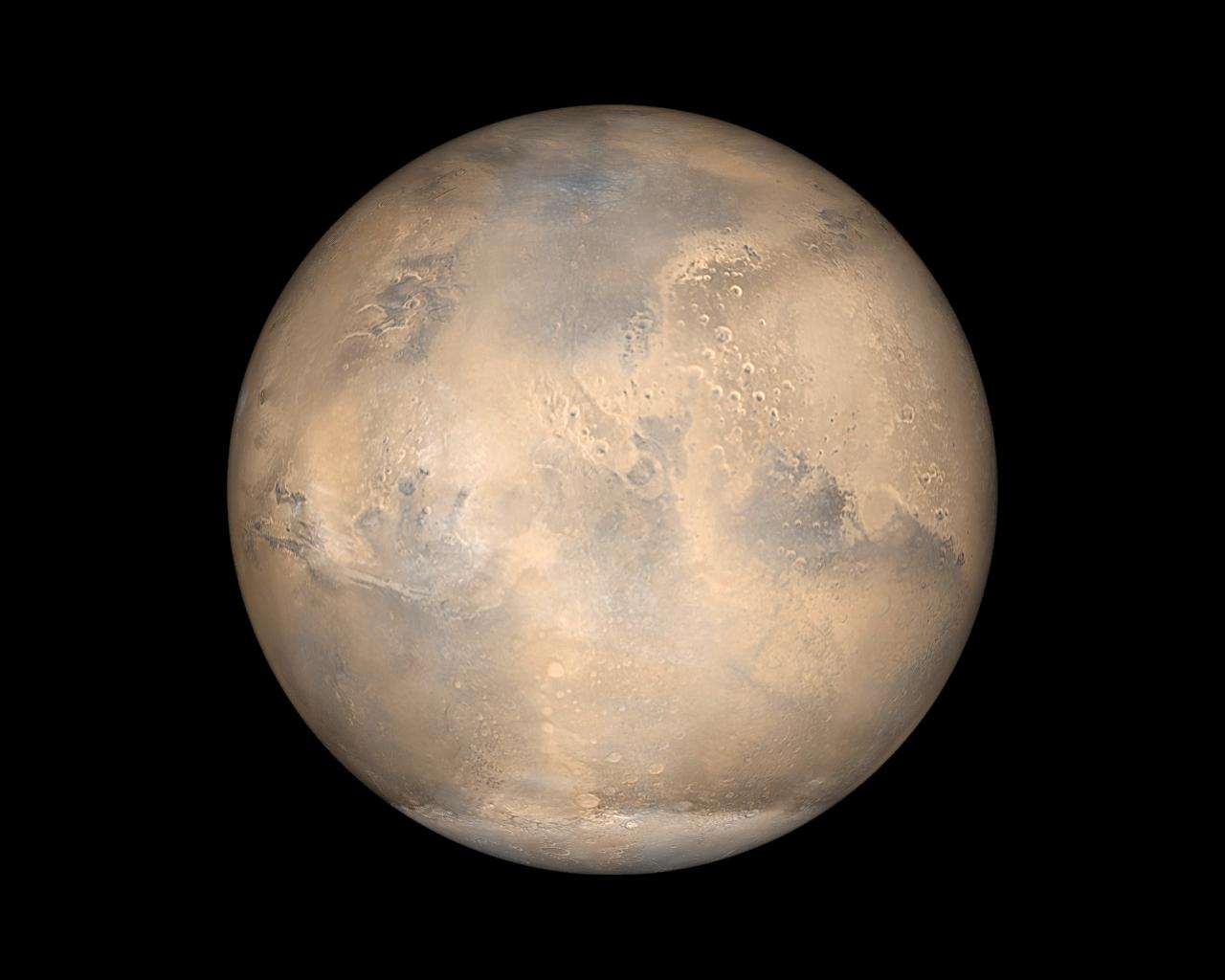

For life to have existed on Mars' surface, the Red Planet would have needed to be much warmer than it is now. Today, its average surface temperature hovers at a balmy minus 81 F (minus 62 C). That's 138 F (77 C) colder than Earth's average temperature, National Geographic reports. But Mars' low temperatures don't rule out the possibility of life. Scientists have evidence that hundreds of thousands of years ago, Mars was much warmer.

Just as Earth goes through ice ages and periods of warming, the climate on Mars changes over time. And just like Earth, the Red Planet's climate oscillations happen because of changes in its orbit of the sun. The time scale of Martian climatic cycles are even similar to that of Earth — both take around 100,000 years to swing between a cold period and a warming period. But climatic swings on Mars are likely much more extreme than those on Earth, NASA's Boston said. That's partially because Mars wobbles much more on its axis than earth does. Earth axis only moves between 22 and 24.5 degrees of tilt, according to NASA. Over the past 3 million years, Mars' axis has moved between an angle of 15 and 30 degrees. More than 3 million years ago, and its axis could have tilted more than 45 degrees.

Mars's climate is currently in the cooler stage of one of these oscillations, Boston said.

"It's overall habitability probably started out pretty high," she added.

An undiscovered underground world

Astrobiologists are just scraping the surface of life-detection on Mars. Literally. While there are no signs of current life on the Martian surface, it's entirely possible life exists where we can't see it — underground.

Boston thinks that Mars, like Earth, emanates heat from its core. Below the surface could exist an unseen temperate world, warm enough for liquid water — and microbial life.

But searching for that life will take many more resources, Boston said. She's hopeful, however, that with a trip to Mars, humans will better understand the Red Planet and its potential to host life. And that includes both past and present.

- Sending Humans to Mars: 8 Steps to Red Planet Colonization

- 7 Theories on the Origin of Life

- Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures

Originally published on Live Science.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.