What was the Reign of Terror?

Thousands of people were arrested and executed during the French Revolution.

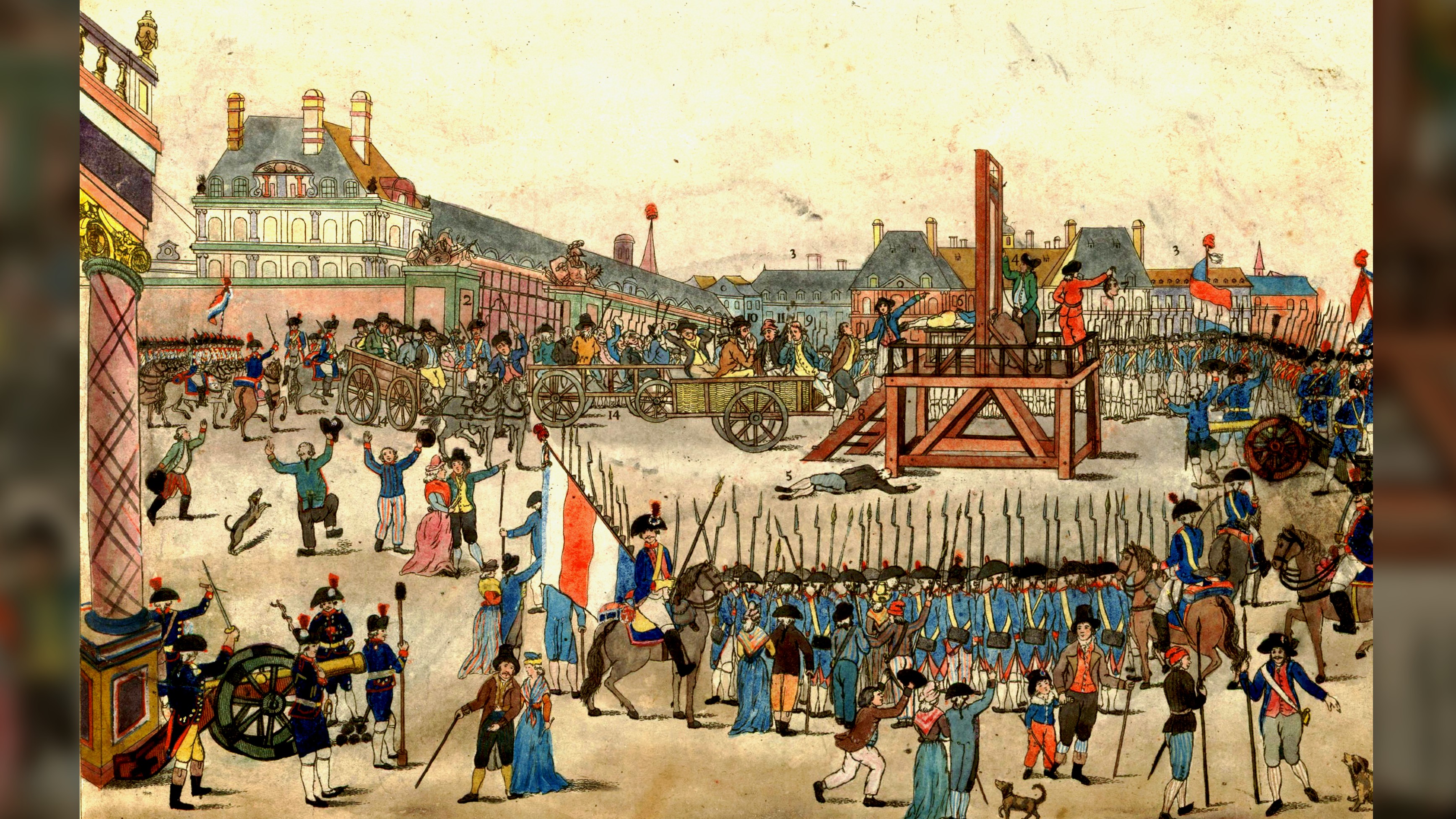

The Reign of Terror, also called the Terror, was a period of state-sanctioned violence and mass executions during the French Revolution. Between Sept. 5, 1793, and July 27, 1794, France's revolutionary government ordered the arrest and execution of thousands of people. French lawyer and statesman Maximilien Robespierre led the Terror, which was caused in part by a rivalry between France's two leading political parties: the Jacobins and the Girondins.

What caused the Reign of Terror?

At the end of the French Revolution, a revolutionary government called the National Convention came into power and formed the first French Republic. The Convention found King Louis XVI guilty of treason in 1792 and beheaded him by guillotine in January 1793. Many areas of France — including Normandy and the city of Lyon — opposed the revolution and rebelled against the new government.

In March 1793, an armed revolt in the Vendée resulted in first several towns and eventually the entire region being captured by a counterrevolutionary army. After a bloody campaign, republic forces defeated the rebellion, resulting in around 200,000 deaths, New Republic reported.

On March 18, 1793, the French army lost the Battle of Neerwinden against a superior Austrian force, causing further opposition to the Convention's rule. "The new regime had to devise a new executive form to replace the monarchy," Peter McPhee, emeritus professor of history at the University of Melbourne in Australia, told All About History magazine.

Related: How many French revolutions were there?

"The critical military and political situation was felt to require an emergency executive," McPhee said. "In April 1793, the National Convention created a 12-man Committee of Public Safety, with the aim of taking the emergency measures necessary to save the revolution." According to McPhee, the Committee arrested alleged opponents of the revolution, who were then tried by revolutionary courts.

On Sept. 5, 1793, the Committee for Public Safety declared France "revolutionary until peace," according to Anne Sa'adah's book "The Shaping of Liberal Politics in Revolutionary France" (Princeton University Press, 2014). This meant that a state of emergency was in force and that the Committee was prepared to use violence against its own citizens to bring stability to France. This triggered what would become known as the Terror, or Reign of Terror.

When was the Reign of Terror?

On Sept. 17, 1793, the Convention passed the Law of Suspects in order to identify and punish any alleged enemies of the revolution. This law also created the Revolutionary Tribunal, which would try accused enemies of the state and execute them if found guilty, according to Ian Davidson's book "The French Revolution" (Pegasus Books, 2016).

The Law of Suspects also authorized the arrest of anyone who "by their writings have shown themselves partisans of tyranny," according to Liberty Equality, and Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, a website run by George Mason University and City University of New York. This prevented any criticism of, or opposition to, the Convention.

On June 10, 1794, the Law of 22 Prairial was passed. It said that those accused of being "enemies of the revolution" were not allowed lawyers for their defense during trial, that there would be no interrogation or evidence presented against them, and that the only possible verdicts were acquittal or death, according to Mike Rapport's chapter in the book "The Routledge History of Terrorism" (Routledge, 2019).

Related: Palace of Versailles: Facts and History

"After June 10, in the six weeks remembered as 'The Great Terror,' 1,376 people were sentenced to death, averaging 30 daily beheadings," Rapport wrote. This continued until the dissolution of the Revolutionary Tribunal in 1795.

Who led the Reign of Terror?

When the Terror began, the most influential group in the Convention was called the Jacobins. The most prominent members of this group were Robespierre (1758-1794), Camille Desmoulins (1760-1794) and Georges Danton (1759-1794), according to McPhee.

"Like so many of his peers, Robespierre saw in the political upheaval of 1788-89 the opportunity to rectify the glaring injustices of absolutism and aristocratic privilege," McPhee said. "Only in July 1793, at the time of the Revolution's greatest crisis, did he enter government as an elected member of the governing Committee of Public Safety, and was widely seen as its key spokesman." Although he occupied no official role in the Committee, Robespierre was the most influential and vocal of its members.

Victims of the Terror

Most of those arrested and executed during the early Terror were members of the aristocracy, priests, members of the middle class and anyone accused of counterrevolutionary activity, according to historian Sylvia Neely's book "A Concise History of the French Revolution" (Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2007).

One of the most famous victims of the Reign of Terror was Marie Antoinette, the deposed queen of France. She was tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal on Oct. 14, 1793, and executed two days later.

Some members of the revolutionary government were also killed during the Terror, including the Girondins, who were, at the time, the largest faction in the Convention. This group was more moderate than the Jacobins and had been sympathetic toward the monarchy. Some of its members had opposed the execution of Louis XVI.

In June 1793, a popular uprising of Parisian workers forced the Girondins from office, leaving the Jacobins as the majority in power. On Oct. 24, 1793, the most prominent Girondin members were put on trial and were executed by guillotine a week later at the Place de la Révolution in Paris.

The executioner took 36 minutes to behead 22 Girondin members, including the corpse of one who had already died by suicide at the trial, according to historian Simon Schama's book "Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution" (Vintage, 1990). A number of other Girondins were later tracked down and either died by suicide or were executed.

Related: What is a coup?

Estimates of the number of arrests during this period range from 300,000 to 500,000, but no one knows the exact number, according to Davidson. "It was certainly tens of thousands and may well have been hundreds of thousands," he wrote.

The number of those executed during the Terror is also uncertain. Official court records of those sentenced to death numbers 16,594, but 18,000 to 23,000 more may have been killed without trial or may have died while imprisoned, according to historian Hugh Gough's book "The Terror in the French Revolution" (Red Globe Press, 2010).

Opposition to the Terror

One of the most prominent opponents of the Reign of Terror was Georges Danton, an influential member of the Jacobins and Robespierre's political rival. By the fall of 1793, Danton argued that the instability threatening the revolution, which had justified the Terror, had ended.

In a speech to the Convention on Nov. 20, 1793, Danton called for an end to the killing. "I demand that we spare men's blood! Let the Convention be just to those who are not proven enemies of the people," he said, according to David Lawday's book "The Giant of the French Revolution: Danton, a Life" (Grove Press, 2010). Danton also co-edited a newspaper that criticized the Terror, the Convention and Robespierre.

In March 1794, Danton and his allies were arrested on a range of charges, including attempting to save King Louis XVI, carrying out treacherous transactions with the Girondins and having secret friendships with foreigners.

No witnesses were allowed to give evidence at the trial, and on April 5, 1794, Danton was sentenced to death. As he was led to the guillotine, he reportedly turned to the executioner and said, "Show my head to the people; it is worth seeing," according to Neely.

How did the Reign of Terror end?

On July 26, 1794, Robespierre delivered a long speech denouncing several members of the Convention and claiming there was a conspiracy against the government, according to McPhee. "The rambling, emotional speech of almost two hours was vague to the point of incoherence because by then almost everyone was suspected of conspiring," McPhee wrote in his book "Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life" (Yale University Press, 2012).

When Robespierre refused to name any of the conspirators, the Convention turned against him, booing and shouting him down to prevent him from speaking. "He was silenced with cries of 'Down with him! Down with him!'" McPhee wrote. "Robespierre tried repeatedly to speak amid the general cacophony. Finally, he shouted: 'I ask for death.'"

The convention voted to arrest Robespierre and declared him and his allies outlaws. At around 2:30 a.m. the next morning, soldiers arrived to arrest the group, and during a struggle, Robespierre was shot in the jaw. Robespierre and his followers were executed on July 28, 1794.

"While most histories link the overthrow of Robespierre and his associates on July 27, 1794, with the end of the Terror, it is more accurate to see a continuing period of 'terror,'" McPhee said. This time, however, it was directed at the Jacobins and lasted until the abolition of the Revolutionary Tribunal on May 31, 1795. This period may have seen up to 6,000 extrajudicial revenge killings across the country, according to McPhee.

Additional resources

- "The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction," by William Doyle (Oxford University Press, 2001)

- "The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution," by Timothy Tackett (Harvard University Press, 2015)

- "Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution," by Simon Schama (Vintage, 1990)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Callum McKelvie is features editor for All About History Magazine. He has a both a Bachelor and Master's degree in History and Media History from Aberystwyth University. He was previously employed as an Editorial Assistant publishing digital versions of historical documents, working alongside museums and archives such as the British Library. He has also previously volunteered for The Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, Gloucester Archives and Gloucester Cathedral.