The rise and fall of the Great Library of Alexandria

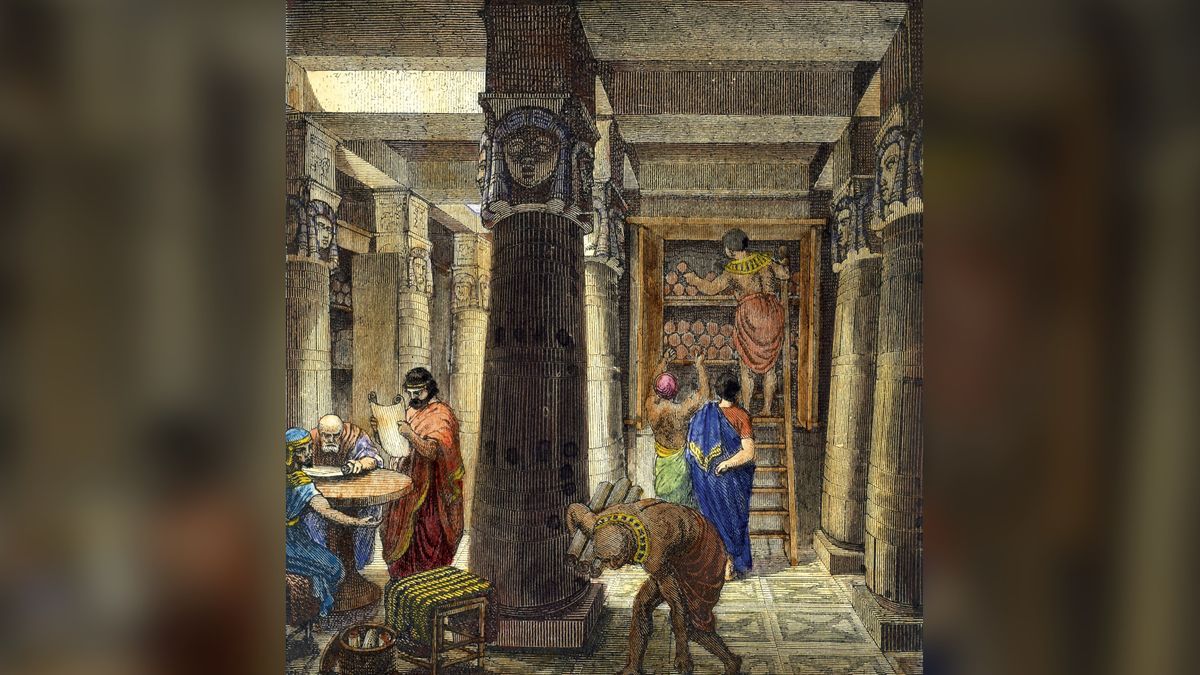

The famous library in Egypt flourished for six centuries and was the cultural and intellectual center of the ancient Hellenistic world before falling into ruin.

The famous library of Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the most important repositories of knowledge in the ancient world. Built in the fourth century B.C., it flourished for some six centuries, was the cultural and intellectual center of the ancient Hellenistic world, and was rumored to contain half a million papyrus scrolls — the largest collection of manuscripts in the ancient world — including works by Plato, Aristotle, Homer, Herodotus and many others. Some of the most brilliant minds of the period worked, studied and taught at the library.

By the fifth century A.D., however, the library had essentially ceased to exist. With many of its collections stolen, destroyed or simply allowed to fall into disrepair, the library no longer wielded the influence it once had.

The story of the Alexandrian Library's rise and demise is still being fleshed out through scholarship and archaeology. But what we do know of this tale is as complex and dramatic as any Hollywood movie.

Library of Alexandria's age and origins

Alexander the Great founded the city of Alexandria, Egypt, at the northwestern end of the Nile delta around 331 B.C. When he died eight years later, his empire was divided among his generals. One of them, Ptolemy I Soter, became the ruler of Egypt and established his capital at Alexandria. Under his reign and the reign of his descendants, the city grew into one of the greatest and most prosperous cities of the Hellenistic period (323 B.C. to 30 B.C.) — a thriving commercial hub and Mediterranean seaport.

"The library was probably created quite soon after the founding of Alexandria around 331 B.C.," said Willeke Wendrich, a professor of Egyptian archaeology and the Joan Silsbee chair of African cultural archaeology at the University of California, Los Angeles. "But it is unclear whether the library was founded by Alexander, Ptolemy I or [his son] Ptolemy II, but it seems likely that it came to fruition under the latter, who ruled from 284 to 246 B.C."

A persistent legend, however, holds that the library began when one of Ptolemy I's subjects, an Athenian named Demetrius of Phalerum, proposed constructing a building to house all the world's known manuscripts, according to according to Britannica. Demetrius' grand design was to erect a place of learning that would rival Aristotle's famous Lyceum, a school and library near Athens. Ptolemy I apparently approved the plan, and soon, a building was erected within the palace precincts.

"It was called the Museion, or 'Place of the Muses,'" Wendrich said; it was named after the muses, the nine Greek goddesses of the arts. (The word "museum" is derived from "museion.")

Zenodotus of Ephesus was reputed to be the first chief librarian, according to Britannica. He was a Greek scholar and poet who served as chief librarian under both Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II. He was responsible for creating the first critical edition of Homer, a work that attempted to determine which parts of the Iliad and the Odyssey were original and which were added by later writers. Zenodotus also edited the work of Hesiod, Pindar and other ancient poets, as well as producing his own poetry.

Library of Alexandria's architecture

The library expanded in size and scope over the years as the Ptolemaic rulers saw the advantages of promoting a center of learning and culture within their city. Generous royal subsidies led to the creation of a complex of buildings surrounding the Museion. Although the precise layout of the library is not known, at its height the library was reputed to have included lecture halls, laboratories, meeting halls, gardens, dining commons and even a zoo, according to the ancient historian Diodorus Siculus. There was also a medical school whose students practiced the dissection of human cadavers — a unique skill that was rarely practiced in Europe before the 15th-century Renaissance.

"The Museion was not a museum in the modern sense of the term, but much more like a university," Wendrich told Live Science. "Here, literary works were recited and theories discussed."

The library's archive, where the manuscripts were held, may have been a separate building from the Museion, though it is not entirely clear. It is possible that, at its height, the library housed upward of half a million separate written works, according to World History Encyclopedia. These written works, called scrolls, were made out of papyrus, a reed that grew along the Nile River. According to Dartmouth College, the reeds were pounded flat to form paper and dried in the sun; the different papers were attached to one another with glue to form a long, continuous paper that could be rolled up.

"The subject of these scrolls contained the totality of knowledge of the ancient [Western] world, ranging from literary works, to philosophical tractates, to scientific explanations," Wendrich said. There were also texts containing religious, mythological and medical subjects.

Library of Alexandria's collections: books and scrolls

The archives contained works by many of the famous Greek writers of classical antiquity, including the philosophers Plato, Aristotle and Pythagoras and the dramatic poets Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. The works of Aristotle were especially prized possessions, according to Britannica. They were, by one account, bought by Ptolemy II, who paid a considerable price for their acquisition. There were also medical texts by Hippocrates; poetry by Sappho, Pindar and Hesiod; and scientific tracts by Thales, Democritus and Anaximander.

The librarians also collected the work of other cultures. According to Britannica, ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, Persian, Assyrian and Indian texts were included in the library. There were also Jewish, Zoroastrian and Buddhist texts.

The Ptolemaic rulers wanted to collect all the world's manuscripts, and to this end, they sent out agents all over the known world in search of papyri. These agents were given explicit orders to find and purchase whatever manuscripts they could find, preferably the oldest and most original, according to Ancient History. Price was not a limitation; the Ptolemaic rulers were willing to pay vast sums for quality manuscripts.

The hunger for manuscripts was so voracious that, according to a popular story noted in World History Encyclopedia, under the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, the son of Ptolemy II, all sailing vessels entering the city's harbor were required to hand over any manuscripts they happened to have onboard. The Alexandrian scribes copied these, keeping the originals and sending the copies back to the ships.

Organizing the scrolls was a gargantuan task. Much like a library today, the scrolls were organized so they could be readily found and accessed by scholars. According to Britannica, the task of organizing the scrolls was given to a man named Callimachus, who worked under the reign of Ptolemy II. He devised a system, called the Pinakes, or "Tables," that classified the scrolls into divisions based on each scroll’s topic. These topics included, for example, natural history, history, poetry, law, rhetoric, medicine and mathematics. The system was akin to a library catalog or bibliography and, according to Britannica, became a model on which other systems of library organization were subsequently based. In addition, each scroll contained a tag that specified the title, author, subject and whether the work contained a single text or multiple texts.

When the scrolls became so numerous that they could no longer be housed in a single building, the ancient Egyptian rulers built a second library, called the Serapeum, according to World History Encyclopedia, which reportedly held over 40,000 scrolls. It was erected near the royal palace in Alexandria sometime between 246 B.C. and 222 B.C. and was dedicated to the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis.

As the library expanded over the centuries, it attracted many of the ancient world's most renowned scholars, philosophers and scientists. These included, among many others, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, Aristarchus of Samos, Euclid of Alexandria and Apollonius of Rhodes. Eratosthenes — a mathematician, geographer and astronomer — was the first person known to calculate the circumference of Earth. He also became the chief librarian of the library under the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, according to Britannica. Aristarchus of Samos was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who first put forward the heliocentric model that placed the sun, rather than Earth, at the center of the known universe. In about 300 B.C., Euclid, known as the "father of geometry," wrote the famous book "Elements," one of the world's most influential works of mathematics. Apollonius of Rhodes was famous for writing a long poem based on the classical tale of Jason and the Argonauts.

The library's burning and demise

Julius Caesar was accused by historians such as Plutarch and Seneca of starting a fire in Alexandria that burned the library to the ground, and for a long time modern historians accepted this version of events. The conflagration occurred during Caesar's occupation of the city in 48 B.C., a time when Caesar was fighting a civil war against his political rivals. According to the story, Caesar, besieged by his rivals, ordered his troops to set fire to enemy ships in the harbor. The historian Plutarch wrote, "Caesar was forced to repel the danger by using fire, which spread from the dockyards and destroyed the Great Library."

But the story is likely exaggerated, most historians now agree. There was a fire during Caesar's occupation, but it is believed that the library was largely unaffected, though some scrolls may have been burned. The Roman historian Cassius Dio, for example, wrote that a warehouse with scrolls located near the docks was burned during this conflict but that the library was untouched. Historians further cite evidence that the library survived by pointing to the writings of later visitors, such as the scholar Strabo, who mention using the library collections in their research.

Wendrich characterized the destruction of the Library of Alexandria as a "slow decay" that "took place over centuries." Indeed, most scholars today are in general agreement that the library suffered a prolonged, painful decline rather than an abrupt, dramatic death. As its influence waned over time, many of its collections were sold or destroyed, and its buildings were ultimately razed or converted into other facilities, such as churches or mosques.

However, this decline was hastened by a number of dramatic events, each of which played a role in lessening the importance of Alexandria as an intellectual center. One such event occurred when the ruler Ptolemy VIII (182 B.C. to 116 B.C.) expelled several scholars, including the chief librarian Aristarchus of Samothrace (not to be confused with Aristarchus of Samos), who had supported Ptolemy VIII's political rival, according to World History. Ptolemy VIII also ordered the expulsion of all non-Alexandrian scholars from the city. This unstable and hostile political environment led to a diaspora of scholars to such places as Athens and Rhodes.

A second event occurred in A.D. 391, when the Roman emperor Theodosius I, who was a devout Christian, issued a decree allowing for the destruction of pagan temples in the empire. Theophilus, the bishop of Alexandria, acted upon this decree by destroying the Serapeum and ordering a church to be built on the ruins, according to World History Encyclopedia.

These and other incidents — such as the Roman emperor Diocletian's siege and sack of the city in A.D. 297 — played roles in further destroying the library and its associated buildings. According to the Coptic bishop John of Nikiu, Diocletian, "set fire to the city and burned it completely."

But perhaps the greatest influence leading to the demise of the library was simply the decline of Alexandria as an intellectual center. Around this time, Rome and Athens gained influence as powerful academic centers, each with their own renowned libraries. This loss of prestige occurred hand in glove with the decline of the city as an important cultural and commercial center. Political and economic problems, coupled with social unrest, prompted many later Ptolemaic rulers to invest fewer resources and less energy in maintaining the library.

"From its heyday in the third century B.C., the intellectual climate fluctuated," Wendrich said. "Some rulers were supportive [of the library], others less so."

In the long term, this meant the gradual dissolution of the library as construction projects halted, other academic institutions attracted scholars and the fortunes of the city waned. Indeed, by the seventh century A.D., when the Arab Caliphate of Omar (also spelled Umar) conquered the city, the library was merely a memory, according to World History Encyclopedia. However, the Christian bishop Gregory Bar Hebraeus, writing in the 13th century, argued that Caliph Omar played a final role in the destruction of the library. When the Muslim army took the city, a general reportedly asked the caliph what was to be done with all the surviving scrolls. The caliph is reputed to have answered, "they will either contradict the Koran, in which case they are heresy, or they will agree with it, so they are superfluous," according to ehistory from The Ohio State University. Consequently, the scrolls were allegedly burned in several great conflagrations that were used to heat the city's bathhouses. However, this story has now largely been discounted by scholars.

Historians and scientists have long lamented the loss of the Great Library of Alexandria — and the destruction of so much knowledge. It is difficult to say for certain what information might have been lost, because there has never been a full accounting of what exactly the library held in its archives.

Editor's note: Originally published on Jan. 17, 2022.

Additional resources

—Read the ehistory entry about the Library of Alexandria from The Ohio State University.

—Learn about the library's demise at My Modern Met.

—Watch a TED-Ed video about the Great Library of Alexandria.

Bibliography

Greatest Greeks, "Demetrius of Phalerum." Demetrius of Phalerum — Greatest Greeks (wordpress.com).

University of Chicago, "Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Book III." https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/3C*.html

World History Encyclopedia, "What Happened to the Great Library at Alexandria?" February 1, 2011. What happened to the Great Library at Alexandria? - World History Encyclopedia

Britannica, "Library of Alexandria." Library of Alexandria | Description, Facts, & Destruction | Britannica

Britannica, "Eratosthenes." Eratosthenes | Biography, Discoveries, Sieve, & Facts | Britannica

World History, "Aristarchus of Samothrace," March 29, 2015. Aristarchus of Samothrace (worldhistory.biz)

History of Information, "Bibliotheca Ulpia." Bibliotheca Ulpia, Probably the Greatest, and Certainly the Longest Lasting of the Roman Libraries : History of Information

World History Encyclopedia, "The Library of Hadrian, Athens," November 5, 2015. The Library of Hadrian, Athens - World History Encyclopedia

Early Church Fathers, "The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu." https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/nikiu2_chronicle.htm

Livius.org, Articles on Ancient History, "Plutarch on Caesar's War in Alexandria." https://www.livius.org/sources/content/plutarch/plutarchs-caesar/war-in-alexandria/

Britannica, “Strabo, Greek Geographer and Historian.” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Strabo

University of Chicago, "Roman History by Cassius Dio." https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/42*.html

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tom Garlinghouse is a journalist specializing in general science stories. He has a Ph.D. in archaeology from the University of California, Davis, and was a practicing archaeologist prior to receiving his MA in science journalism from the University of California, Santa Cruz. His work has appeared in an eclectic array of print and online publications, including the Monterey Herald, the San Jose Mercury News, History Today, Sapiens.org, Science.com, Current World Archaeology and many others. He is also a novelist whose first novel Mind Fields, was recently published by Open-Books.com.