The Roman Colosseum: Facts about the gladiatorial arena

The Colosseum is an icon of ancient Rome with a long and remarkable history.

The Colosseum was the largest amphitheater built in ancient Rome. The massive arena held thousands of spectators, who packed the stands to watch gladiators battle to the death and fight exotic animals, such as lions. Built in A.D. 72, the four-story amphitheater soon towered nearly 165 feet (50 meters) high. The Roman Empire used the Colosseum for more than four centuries before it ceased to function as a sporting arena as spectators lost interest in the type of grisly public entertainment it provided.

After the Colosseum stopped hosting events, Roman citizens quarried the Colosseum's stones for other building projects, John Henry Parker wrote in his book "The Archaeology of Rome: The Flavian Amphitheatre" (J. Parker and Co., 1876). The massive structure served several purposes after the fall of the Roman Empire, including as a fortress in the 12th and 13th centuries. Earthquakes, bad weather and neglect over the centuries caused the ancient structure to deteriorate further.

Preservation efforts, supported by Pope Pius VIII, according to Britannica, began in the mid-19th century. In the 1990s, archaeologists started a major project at the site to preserve as much of the original structure of the Colosseum as possible. It is now the biggest tourist attraction in Italy; every year, millions of visitors from across the world flock to the impressive site. Nowadays, the Colosseum is one of the most iconic remaining structures from ancient Rome.

Before the Colosseum

On July 18, A.D. 64, a fire broke out in the Circus Maximus, a chariot-racing stadium. The fire spread rapidly across the densely packed wooden structures of Rome, causing a devastating blaze. Contrary to popular belief, the tyrannical Emperor Nero did not fiddle while Rome burned.

For starters, Nero played the lyre, not the fiddle. And he was, in fact, miles away, in Antium, when the conflagration began. It is impossible to know how the fire started, but the aftermath was devastating.

The fire raged for six days, destroying much of the city and leaving only four of Rome's 14 districts untouched, according to the Roman historian Tacitus. With large areas of land decimated, Nero seized the opportunity to build himself a grand palace over 200 acres (81 hectares) of land.

"When Nero unveiled plans for a huge new palace, the Golden House (complete with a revolving dining room and perfume dispensers) which would gobble up huge parts of the city, some began to speculate he had started the fire himself to make way for the vanity project," All About History, a Live Science sister publication, reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Domus Aurea (Golden House) symbolized private imperial power. After Nero's death by suicide in A.D. 68, the palace complex was put to other uses in the public interest, with some parts torn down and replaced with new buildings.

The palace's artificial lake had dominated the area where the Colosseum now stands. Emperor Vespasian, who began his reign shortly after Nero's death, decided to build the Colosseum in its place, and intended to "obliterate Nero's memory" in Rome, Mary Beard, a professor of classics at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., wrote in "Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures and Innovations," (Profile Books, 2013).

Unfortunately, it did the opposite: The name "Colosseum" comes from the nearby Colossus statue that had been commissioned by (and possibly depicted) Nero and stood as part of the Domus Aurea.

When was the Colosseum built?

Emperor Vespasian (who ruled from A.D. 69 to 79) commissioned the construction of the Colosseum in A.D. 72, as a gift to the Roman people. Situated on the east bank of the Tiber River, the Colosseum opened its doors in the center of Rome in A.D. 80, when Vespasian's son Titus dedicated the Colosseum to the people and announced 100 days of games and events to commemorate the occasion, according to "The Colosseum" (Profile Books, 2011), a book co-authored by Beard and British historian Keith Hopkins.

At this time, the Colosseum was known as the Flavian Amphitheater, after the Flavian dynasty of emperors that had started with Vespasian.

The Colosseum was exceptionally famous during its active years in the Roman Empire. The first-century poet Martial wrote an ode to the Colosseum, comparing it with other wonders of the world, such as the Egyptian pyramids and Babylon.

"You only have to look at the façade of the Colosseum to understand what is special about the architecture," Heinz-Jürgen Beste, a scientific adviser at the German Archaeological Institute in Rome who has worked on the research and restoration of the Colosseum since 1995, told Live Science in an email.

"Each storey consists of eighty arches separated by pillars with half-columns in front: those of the lowest storey are Doric, those of the central storey are Ionic and those of the third storey have a Corinthian order," he added. "The proportions of the respective orders are not the same, however, because the pillars — and thus the arches — of the Doric order are higher than those of the two upper ones."

The Colosseum became a model for amphitheaters across the Roman Empire, according to Beard and Hopkins.

Gladiator fights and animal hunts

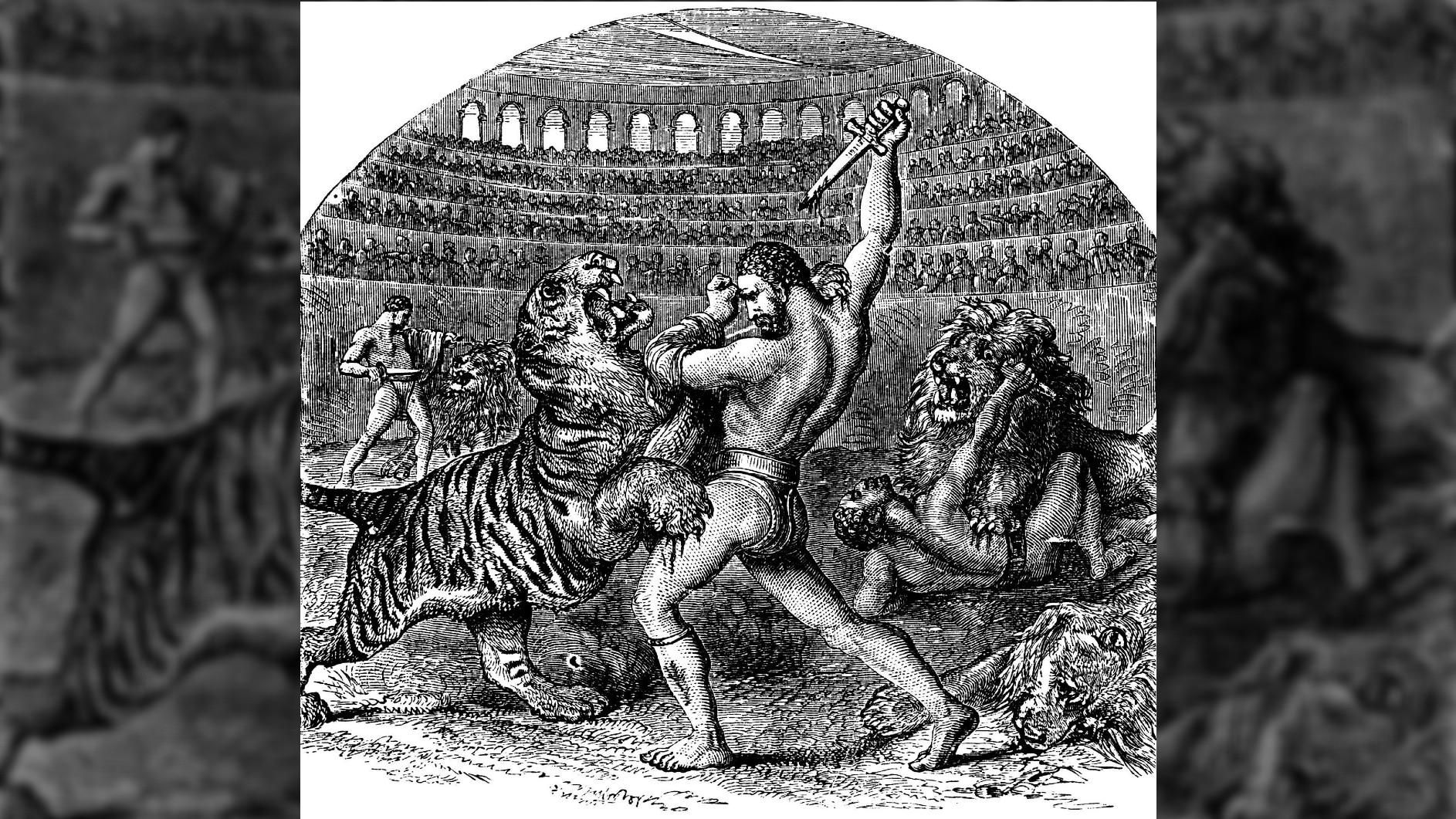

The Colosseum hosted a variety of gory spectator events in its first 100 days. Approximately 9,000 animals were slaughtered during the animal hunts, according to the Roman historian and politician Cassius Dio, who lived circa A.D. 155 to 235. Many gladiators, slaves and prisoners were likely slaughtered during the opening festival of the Colosseum, but no numbers are recorded.

"Since the façade of the Colosseum resembles that of a theatre, it is only because of the oval shape that we can tell that gladiator games took place there," at least from an architectural standpoint, Beste said. "However, the many entrances and staircases show that the Colosseum was built to accommodate a large crowd."

The sports at the Colosseum were certainly popular with the people of Rome, despite objections from the city’s greatest minds.

"Philosophers objected to arena spectacles on the grounds that the spectators lost their self-control and got sucked into the fanatical reactions of the crowd, but all classes of persons attended," Kathleen M. Coleman, a professor of classics at Harvard University, told Live Science in an email.

Gladiatorial fights were some of the deadliest events held at the Colosseum. Before the opening of the new amphitheater, gladiatorial fights were showcased in the various forums around the center of ancient Rome, according to historian Marcus Junkelmann in the multi-author book "Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome" (University of California Press, 2000). After the Colosseum was built, the gladiators found a new stage.

"Gladiatorial casualties were higher than any ever known before," Eckart Köhne, archaeologist and museum director, wrote in "Gladiators and Caesars" about the opening of the Colosseum. Competing in life-and-death battles, the men known as the gladiators would fight each other with a variety of weapons — such as swords, spears and nets — for the entertainment of the onlookers sitting in the stands.

Gladiatorial combat began as a spectacle performed at the funerals of eminent Romans. During these battles, enslaved people or prisoners of war would fight to the death for the entertainment of the funeral-goers, Junkelmann wrote. From the second century B.C., the sport grew, and official training schools were established by entrepreneurs who recruited and bought men to be coached in the skills of the gladiator.

"The gladiators were either enslaved persons or free persons who temporarily relinquished the privileges of freedom to adopt enslaved status, and so they were essentially regarded by the spectators as commodities," Coleman said.

Gladiatorial schools continued to be privately owned after the transition from the republic to the empire in the late first century B.C., but gladiatorial combat operated under state control. Imperial schools were also established, the most important of which was located next to the Colosseum. A passageway ran from the school straight into the amphitheater so gladiators could travel to their gruesome combat displays without being seen, according to Junkelmann.

The exact number of gladiatorial deaths at the Colosseum over the centuries is unknown, but gladiators were not the only human fatalities at the amphitheater.

A day of entertainment would have included a variety of events, including fights between untrained novice warriors.

"Usually condemned criminals or prisoners of war, they were given none of the training or privileges of gladiators, but instead were expected to fight enthusiastically, usually in recreations of great battles from the past," archaeologist M. C. Bishop wrote in "Gladiators" (Casemate, 2017).

Gladiators didn't just fight each other; they also hunted exotic beasts that were shipped in from around the world. In these performances, known as "venationes," the animals were kept in cages below the floor of the amphitheater and were then pitted against Rome's gladiatorial heroes in a battle to the death. The beasts that faced the gladiators included leopards, boars, elephants, crocodiles and hippos.

Commodus at the Colosseum

In the second century A.D., one Roman emperor decided to display his prowess by fighting in the arena. Dressed as the Roman god, Mercury, Commodus (who ruled from A.D. 176 to 192) battled gladiators, people with disabilities (including those who had lost their feet from injury or illness) and animals in an amphitheater.

"He himself would enter the arena in the garb of Mercury, and casting aside all his other garments, would begin his exhibition wearing only a tunic and unshod," the historian Dio wrote in his eyewitness account.

"When the emperor was fighting, we senators, together with the knights, always attended," he added. The senators attended because Commodus mandated their presence; Dio recalled how the emperor killed an ostrich and displayed the "severed head in one hand and his bloody sword in the other, implying that he could treat them [the senators] the same way," according to a translation of his writings. Coleman told Live Science that Commodus was presumably fighting in these gladiatorial bouts at the Colosseum.

"Dio reports that many spectators from among the people at large either did not come or only glanced at the show and then left, because they were afraid that they might end up as victims in the arena," she said.

What else did the Romans use the Colosseum for?

Aside from gladiatorial and animal competitions, other spectacular events delighted crowds at the Colosseum. Mock naval battles were reported to have taken place in the amphitheater when it first opened. However, these reports have puzzled historians and archaeologists.

Dio recorded that a mock battle was staged in the first 100 days of the Colosseum's opening and that horses and bulls were brought to swim in the flooded arena. This would not have been possible in the Colosseum as it stands today; according to Beard and Hopkins, it would have been impossible to waterproof the basement. Dio may have been mistaken, as naval battles are known to have been performed in a separate purpose-built stadium.

Digging deep basins in the floor of large amphitheaters like the Colosseum was commonplace in the Roman Empire. In "Gladiators and Caesars," Junkelmann suggested that this could have been the case at the Colosseum and that the basin would have been covered during regular performances. The basin could be filled and used for the hunting of semiaquatic animals such as crocodiles and hippos.

While the Colosseum is famous as a prominent setting for Christian martyrdom throughout the Roman Empire, there is little evidence to suggest that Christians were executed in the amphitheater, according to Roger Dunkle, formerly a professor of classics at Brooklyn College, City University New York.

"The tradition that Ignatius of Antioch was the first Christian martyred in the Colosseum during the reign of Trajan is not supported by any reliable evidence. On the other hand, despite the lack of evidence, it seems logical that at least some Christians were martyred in the Colosseum’s arena," he wrote in "Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome" (Routledge, 2008).

After the gladiators

"There is no fixed date when the gladiator fights ended," Beste told Live Science. "Due to missing inscriptions and gravestones of killed gladiators, it can be assumed that gladiator games ended in some areas of the Roman Empire as early as 250 A.D. In cities such as Milan and Rome, on the other hand, the end of gladiator games is assumed to be between 390-410 A.D."

According to Beste, animal hunts remained a fixture at the Colosseum until around A.D. 523, when prefect Anicius Maximus recorded the last known event. From then, it is presumed that the Colosseum ceased to function as an arena.

Coleman agreed with Beste, saying there is proof of gladiatorial combat at the Colosseum into the fifth century A.D. and accounts of animal hunts there into the sixth century.

"We do not know why the games ceased, but it may have been a combination of financial pressure and changing tastes," Coleman said. A series of severe earthquakes between the fifth and early sixth centuries A.D. decimated parts of the Colosseum's structure. The basement was filled in after this, and although the amphitheater was restored several times by various Roman prefects, from A.D. 521 on, only the seats for senators were restored. Beste suggested that, from this point onward, only a few spectators could enter the Colosseum.

"The Colosseum was so destroyed from 530 A.D. that it was not worth restoring," Beste said. The venationes, which had still been taking place, moved to the nearby Circus Maximus, which was less susceptible to earthquake damage.

The Romans quarried the amphitheater's rich materials to help build new structures in the city, further adding to the damage.

What happened to the Colosseum after the Roman Empire?

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in A.D. 476 (the eastern half, also known as the Byzantine Empire, persisted until 1453), people continued to strip the Colosseum of its materials during the Middle Ages. "The outer arcade on the south-western side of this colossal building was entirely destroyed in the middle ages by the Pontifical families, who used it as a stone-quarry for building their great palaces," Parker wrote.

Serving as a fortress for the prominent Frangipani and Annibaldi families during much of the 12th and 13th centuries, the Colosseum was partially destroyed when a great earthquake hit Rome in 1349. The outer ring of the south side collapsed, and the ruins were, once again, quarried.

According to Parker, the senate gifted parts of the building to the Chapter of the Lateran to be used as a ward for their hospital in 1381. Their mark can still be seen carved into some of the Colosseum's arches.

Under different popes during the 16th to 18th centuries, plans were made for the Colosseum to be turned into a wool factory and a church. "Ultimately, a church was built there in the early modern era (sixteenth century)," Coleman told Live Science.

Around 1750, Pope Benedict XIV consecrated the site of the Colosseum to the memory of the Christian martyrs who were allegedly killed there.

The Colosseum still stands in the center of Rome as one of the most recognizable buildings of the ancient world. Millions of tourists visit the site every year, and it is a must-see destination for sightseers in the city.

"The Colosseum is a building of incomparable artistic value that documents European history well over the course of almost two thousand years," Beste told Live Science.

"It is important to preserve the Colosseum because it was a central building in ancient Rome that survives today, albeit in a ruined state, and it is a reminder that human beings have favored gruesome activities and justified them," Coleman said.

Additional resources:

Why not visit the website of the Colosseum Museum in Rome. Or take a free online class on "Roman Art and Archaeology" led by David Soren, a professor of classics and anthropology at the University of Arizona, on the website Coursera. You can also see the monumental building up close by watching travel personality Rick Steves explore it in "Rick Steves Europe."

Emily is the Staff Writer at All About History magazine, writing and researching for the magazine's content. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree in History from the University of York and a Master of Arts degree in Journalism from the University of Sheffield. Her historical interests include Early Modern and Renaissance Europe, and the history of popular culture.