The Roman Empire: Rulers, expansion and fall

While many date the collapse of the Roman Empire to the fifth century, in reality it didn't fall until AD 1453.

The Roman Empire began in 27 B.C., when Octavian, Julius Caesar's adopted son and heir, was granted the title "Augustus," meaning "revered one," by the Roman senate. This new title signified Octavian's elevation to the position of emperor in all but name, ending the Roman Republic, according to many modern historians.

Octavian was granted this title after emerging victorious from a series of civil wars triggered by the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. During these wars Mark Antony, Caesar's former general, fought for control of the Roman world against some of Caesar's assassins, and later he allied with Cleopatra to fight against Octavian

While some of the republic's institutions, such as the senate, continued to function after 27 B.C., their powers were much reduced. Power instead became focused on Augustus and his successors.

Pax Romana

Modern-day historians sometimes use the phrase "Pax Romana" (Roman Peace) to describe the period between 27 B.C., when Octavian was given the title Augustus, and A.D. 180, when Emperor Marcus Aurelius died. This phrase is sometimes used because it was a relatively stable period in Roman history, compared to periods before and after these years.

However, relative is the operative term as there were plenty of wars, assassinations and civil strife within the Roman Empire during this period. Augustus tried, in some ways, to portray his period of rule (which lasted until his death in A.D. 14) as a relatively peaceful time.

"Among the many images of him [Augustus], relatively few, especially of the statues, busts and reliefs, depict him as a general," wrote Adrian Goldsworthy, a historian, in his book "Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World" (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2016).

While Augustus wanted to depict his period of rule as peaceful, the reality was quite different. During Augustus' rule, the Roman army fought in Iberia, conquering areas that were not already under Roman control. The army also advanced deep into what is now Germany in the hopes of incorporating it into the Roman Empire. This met with disaster when three legions, including their commander, Quintilius Varus, were completely annihilated at the Battle of the Teutoburg forest in A.D. 9.

The Roman historian Suetonius (who lived around A.D. 70 to 122) claimed that this loss had a profound impact on Augustus. "They say that he was so greatly affected that for several months in succession he cut neither his beard nor his hair, and sometimes he would [bash] his head against a door, crying: 'Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!' And he observed the day of the disaster each year as one of sorrow and mourning," Suetonius wrote (translation by John Carew Rolfe).

The Roman historian Tacitus (circa A.D. 55 to 120) claimed that Augustus, in his final will, advised his successor Tiberius (Augustus's adopted son) to not expand the empire but keep it within its present frontiers. While Tiberius, who reigned from A.D. 14 to 37, largely kept the empire within its frontiers, future emperors did not — with some future military adventures also ending in disaster.

Related: 8 powerful female figures of ancient Rome

There was also no shortage of strife and civil war during the "Pax Romana." Emperor Caligula, who reigned from A.D. 37 to 41, was killed by members of the Praetorian Guard (the unit in charge of protecting the emperor) and Nero's reign (A.D. 54 to 68) ended in civil war. Emperor Domitian (reign A.D. 81 to 96) was also assassinated during the so-called Pax Romana.

The most enduring military conquest made after the death of Augustus came during the reign of Emperor Claudius, who ruled from A.D. 41 to 54. He and his successor, Nero, succeeded in invading and occupying England. The attempt almost failed, and the Romans came close to being expelled while battling the Iceni queen Boudicca in A.D. 60 to 61. Ultimately the Roman Empire was victorious and held onto England until A.D. 410.

However, the Romans' attempts to invade Scotland were unsuccessful. One notable attempt occurred during the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (r. A.D. 138 to 161 ) who captured part of Scotland and built a series of fortifications there that modern-day historians sometimes call the "Antonine Wall." His successors were unable to hold onto even a portion of Scotland and Roman troops eventually retreated to Hadrian's Wall, which is located in northern England around AD 160.

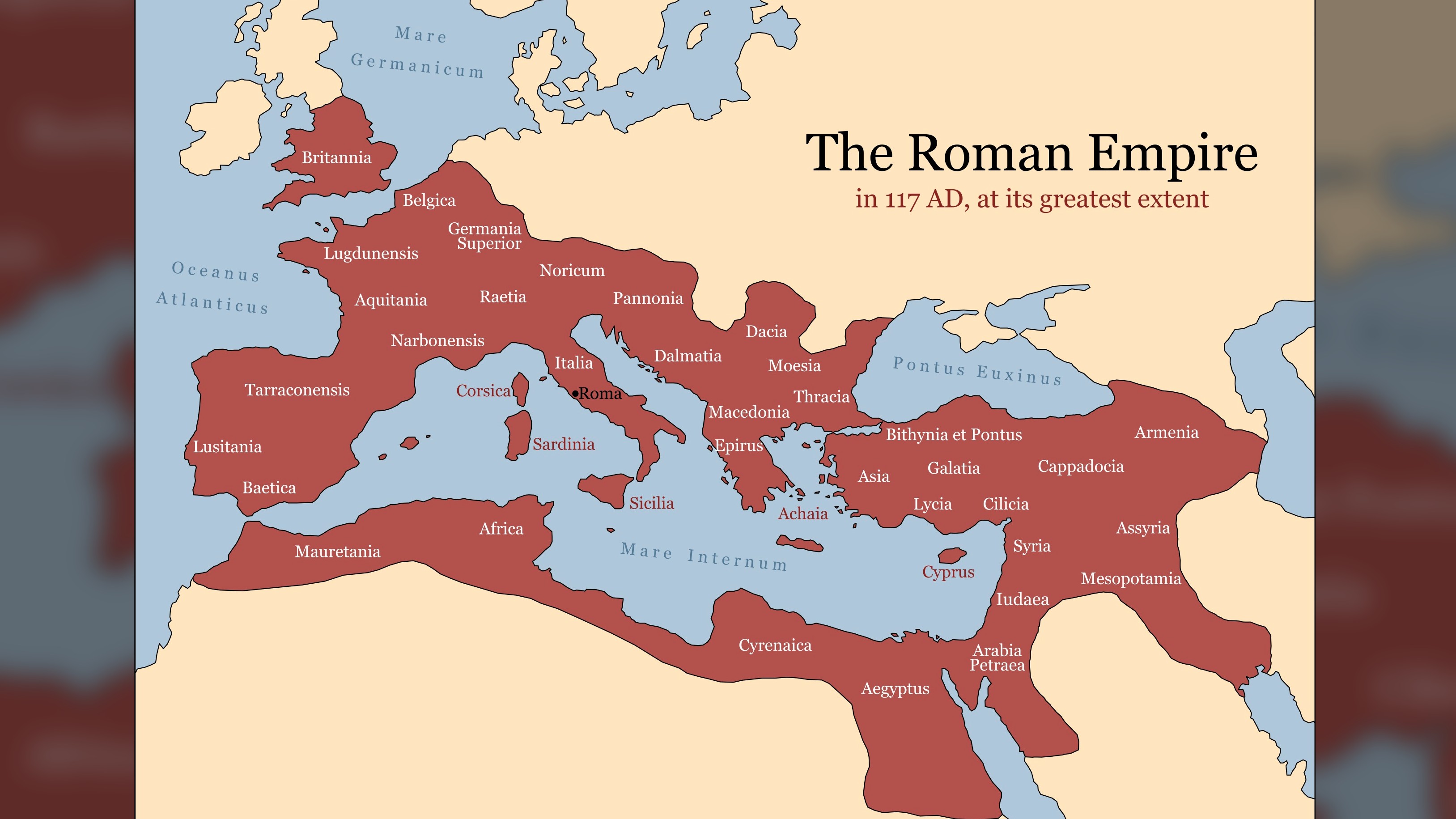

Other Roman rulers sought to expand the empire during their reign.Emperor Trajan (r. A.D. 98 to 117) launched an ambitious attempt to expand the Roman Empire, conquering Dacia, a territory located around modern-day Romania. The Romans held onto Dacia until the A.D. 270s.

Trajan also attempted to invade and occupy what is now Iraq. While Trajan succeeded in advancing to the Persian Gulf his forces could not hold onto the territory, and his successor Hadrian (r. A.D. 117 to138 ) withdrew from Iraq and focused on fortifying and consolidating the empire's existing borders.

There were also numerous rebellions throughout the empire during the Pax Romana. In Judea, an unsuccessful revolt by the Jews in A.D. 66 to 74 resulted in the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, the most holy site for Jews, by Roman forces; the abandonment of Qumran, the site where the Dead Sea Scrolls were stored in nearby caves; and the destruction of a rebel force at Masada.

There were more rebellions in Judea during the Pax Romana, with one rebellion, which ended in A.D. 136, resulting in the slaughter of more than half a million Jews by Roman forces, the survivors fanning out around the world.

End of the Pax Romana

After Marcus Aurelius died in A.D. 180 his son, Commodus, became emperor.. Commodus's rule was plagued by infighting. A failed attempt to assassinate the emperor in A.D. 182 led to the murders of a large number of people accused of being involved in the conspiracy, including many of Marcus Aurelius's senior advisors, wrote David Potter, professor of Greek and Roman history at the University of Michigan in the book "The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395 second edition" (Routledge, 2014).

On the evening of Dec. 31, A.D. 192 to Jan. 1, A.D. 193 Narcissus, an athlete who trained Commodus in gladiator fighting, killed the emperor. Civil war then engulfed the Roman Empire, and A.D. 193 A.D. became known as the year of the five emperors.

Troops loyal to a military commander named Septimus Severus (r. A.D. 193 to 211) ultimately prevailed in the civil war. After gaining control of the empire Severus embarked on a policy of trying to expand the empire's borders, launching a military expedition into modern-day Syria and Iraq.

While Severus succeeded in conquering and controlling the area it came at a great cost. The contemporary historian Cassius Dio (c. A.D. 155 to 235) wrote that the new territory was a "cause of constant wars and of enormous expense." (Translation by David Potter.) Severus also tried to conquer Scotland but died while on campaign.

After Severus' death, a lengthy period of instability ensued, which was exacerbated by invasions from assorted "barbarian" groups, including invasions of Greece by the Goths.

A series of epidemics, sometimes called the "Plague of Cyprian" (named after a bishop of Carthage who believed the world was coming to an end) ravaged the Roman Empire between A.D. 250 and 271, killing at least two Roman emperors.

Related: 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

The plague's effects were horrible. "The intestines are shaken with a continual vomiting, [and] the eyes are on fire with the injected blood," Cyprian wrote in a work called "De mortalitate" (translation by Philip Schaff).

Reforms of Diocletian

Emperor Diocletian's reign from A.D. 284 to 305 saw a brief period of relative stability as the emperor enacted a series of radical reforms. Instead of one emperor, Diocletian created a "tetrarchy" consisting of four co-emperors — although he was the most important of the four — in an effort to stabilize the empire's government.

Diocletian reformed the economy, coinage, justice system and provincial structure to try and balance the teetering empire. He also sought to prevent the sons of emperors from succeeding their fathers, instead relying on a system of appointments made by the two most senior emperors.

Diocletian abdicated in A.D. 305, hoping that the tetrarchy system of four co-emperors would be able to peacefully transition, noted Potter. However, the empire fell into civil war not long after Diocletian abdicated, and the tetrarchy system was soon abandoned.

Rise of Christianity

As the Roman Empire was ravaged by civil war, invasions and epidemics, Christianity became increasingly popular. The Plague of Cyprian played an important role in Christianity's rise, noted Candida Moss, a professor of religion at the University of Birmingham, U.K., in an article published in 2014 on CNN.

"The fact that even Roman emperors were dying and pagan priests had no way to explain or prevent the plague only strengthened the Christian position. The experience of widespread disease and death and the high probability that they themselves might die made Christians more willing to embrace martyrdom," Moss wrote.

Christians still faced persecution despite the growing popularity of their religion. Diocletian in particular persecuted Christians, passing edicts decreeing that Christian churches and manuscripts should be destroyed, any freedmen who became Christians should be enslaved again and that Christians could not seek legal recourse if they were assaulted. His orders were enforced to varying degrees across the empire, noted Potter.

The civil wars that followed Diocletian's abdication changed the situation for Christians dramatically. While people today sometimes give Constantine sole credit for legalizing Christianity, in reality there were several competing rulers who issued edicts legalizing Christianity during the 310s.

Ultimately Constantine — who was the son of one of the four emperors — prevailed in the civil wars, becoming ruler of the entire Roman Empire in A.D. 324, before dying in A.D. 337. Many ancient Christians and modern-day historians believe that Constantine himself converted to Christianity during his reign and was baptized before his death.

In the decades that followed Constantine's death the Roman Empire again fell into civil war, although Christianity gradually grew to become the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380, with pagan groups being persecuted.

Fall of the Roman Empire

During Constantine's reign he ordered the construction of a new city called Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). After his death the emperor's descendants fought each other for control of the empire.

A system gradually came into place where there was one emperor in control of the western half of the Roman Empire while a second emperor (ruling from Constantinople) controlled the eastern half. The two emperors at times worked together and at other moments were in conflict with each other. This schism could also be seen in Christianity, as differences between clerics in the eastern and western half of the empire resulted in the rise of the Roman Catholic Church based in the west and Orthodox churches in the east.

The fates of the western and eastern halves of the Roman Empire were dramatically different. Throughout the fourth and fifth centuries the eastern half of the Roman Empire continued to thrive and was able to repel various "barbarian" invasions. The western half went into decline, gradually losing territory to the various groups that were moving across the Western Roman Empire's borders.

An assortment of groups including the Goths, Vandals and Huns took over the western half of the Roman Empire. Ancient Rome was sacked twice, first by the Goths in A.D. 410 and then by the Vandals in A.D. 455. In A.D. 476 the Western Roman Empire officially ceased to exist.

Related: Why did Rome fall?

But the eastern half, based at Constantinople, continued to thrive, becoming what modern-day historians often call the Byzantine Empire. However, while modern-day historians use this term the people who lived in this empire continued to call themselves Roman. It wasn't until 1453 — when Constantinople was captured by the Ottoman military — that the Roman Empire truly ceased to exist.

Additional resources

- View AI portraits of Roman emperors

- Mary Beard's book "SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome" (Liveright, 2015) provides a detailed look at Roman history

- Learn more about why Rome itself fell in Adrian Goldsworthy's book "How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower" (Yale University Press, 2009)

- Also check out Goldworthy's book "In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire" (Yale University Press, 2016)

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.