Roman-era Egyptian child mummy scanned with laser-like precision

Highly focused X-ray beams targeted small objects inside the mummy.

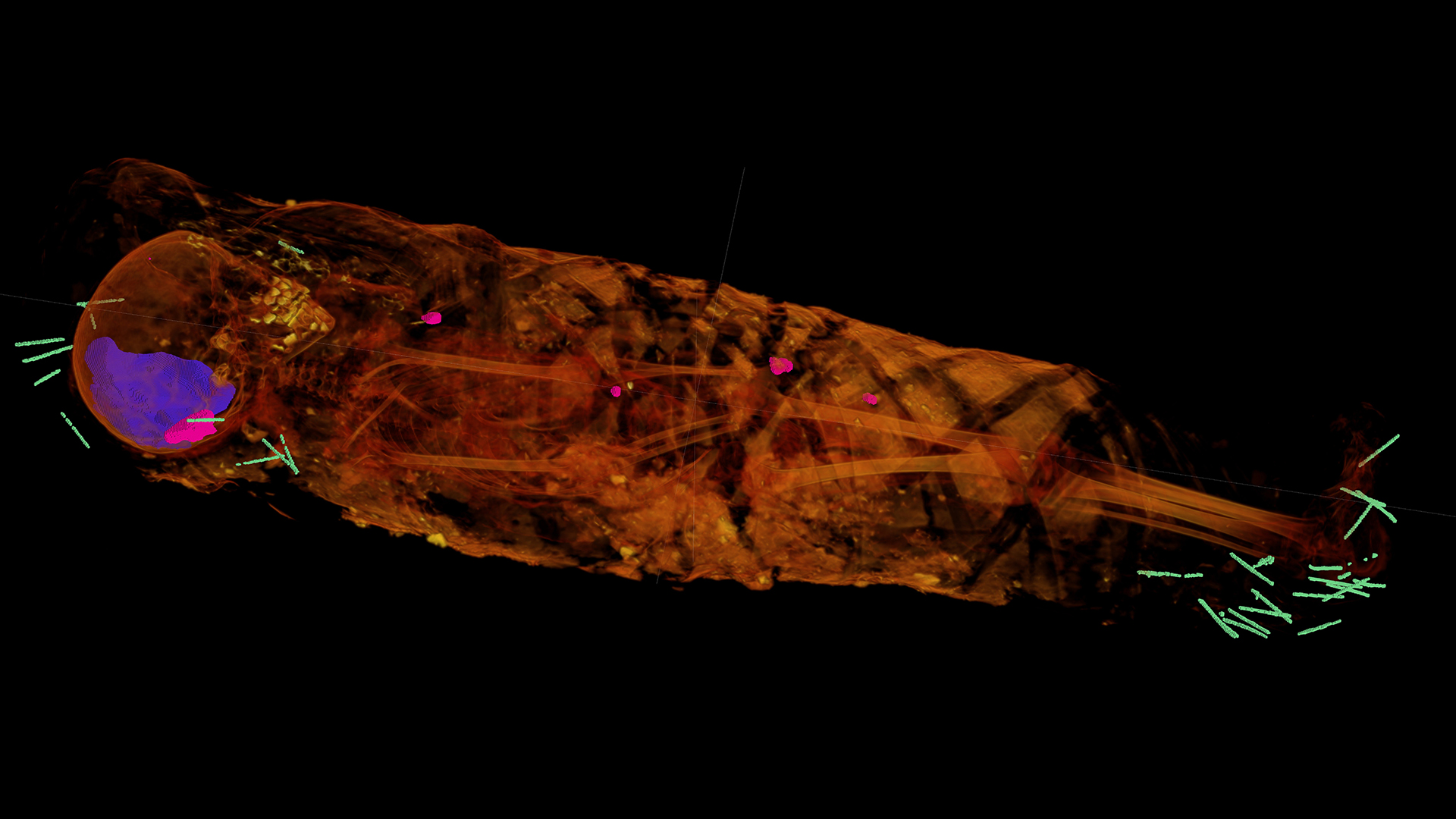

An Egyptian mummy that was decorated with a woman's portrait contained a surprise — the body of a child who was only 5 years old when she died. Now, scientists have learned more about the mysterious girl and her burial, thanks to high-resolution scans and X-ray "microbeams" that targeted very small regions in the intact artifact.

Computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans of the mummy's teeth and femur confirmed the girl's age, though they showed no signs of trauma in her bones that could suggest the cause of her death.

Targeted, high-intensity X-rays also revealed a mysterious object that had been placed on the child's abdomen, scientists reported in a new study.

Related: Image gallery: The faces of Egyptian mummies revealed

Scans performed on the mummy about two decades ago were low contrast, and many details were hard to see. For the new analysis, researchers conducted new CT scans to visualize the mummy's structure in its entirety. They then focused on specific regions using X-ray diffraction, in which a tightly concentrated beam of X-rays bounces off the atoms in crystalline structures; variations in the diffraction patterns reveal what type of material the object is made of.

This is the first time that X-ray diffraction has been used on an intact mummy, said lead study author Stuart Stock, a research professor of cell and developmental biology in the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

The mummy, known as "Hawara Portrait Mummy No. 4," resides in the library of the Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois. It was excavated between 1910 and 1911 from the ancient Egyptian site of Hawara, and it dates to around the first century A.D., when Egypt was under Roman rule.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"During the Roman era in Egypt, they started making mummies with portraits attached to the front surface," Stock told Live Science. "Many thousands were made, but most of the portraits have been removed from the mummies we have — maybe only 100 to 150 still have the portrait attached to the mummy," he said.

Though the portrait on Mummy No. 4 showed an adult woman, the small size of the mummy hinted otherwise — and the scans confirmed that the mummy was a child, still so young that none of her permanent teeth had emerged. Her body measured 37 inches (937 millimeters) from the top of her skull to the soles of her feet, and the wrappings added another 2 inches (50 mm), according to the study.

The researchers also detected 36 needle-like structures in the case — 11 around the head and neck, 20 near the feet and five by the torso. X-ray diffraction determined that these were modern metal wires or pins that may have been added to stabilize the artifact sometime during the last century.

One surprising find was an irregular layer of sediment in the mummy's wrappings, perhaps mud that had been used by the attending priests to secure the mummy's bandages, Stock suggested. Another puzzling discovery was a small, elliptical object about 0.3 inches (7 mm) long, which the researchers found in the mummy's wrappings over the abdomen, dubbing the object "Inclusion F."

X-ray diffraction showed that it was made of calcite — but what was it? One possibility is that it could be an amulet included because the child's body was damaged during mummification, Stock said. After such a mishap, priests would often place an amulet such as a scarab over the damaged body part to protect the person in the afterlife, and the newfound calcite "blob" was about the right size and in the right position for it to be a protective scarab, Stock explained.

However, the resolution of the CT scan wasn't high enough to show carved details in the object, so it's impossible to say for sure what it could be, he added.

"Every time you go into a study like this, you get good answers. But then you just raise more questions," Stock said.

The findings were published online Nov. 25 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Editor's Note: The article was updated on Nov. 30 to note that the mummy resides in the library of the Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, rather than in the collection of Northwestern University's Block Museum of Art.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.