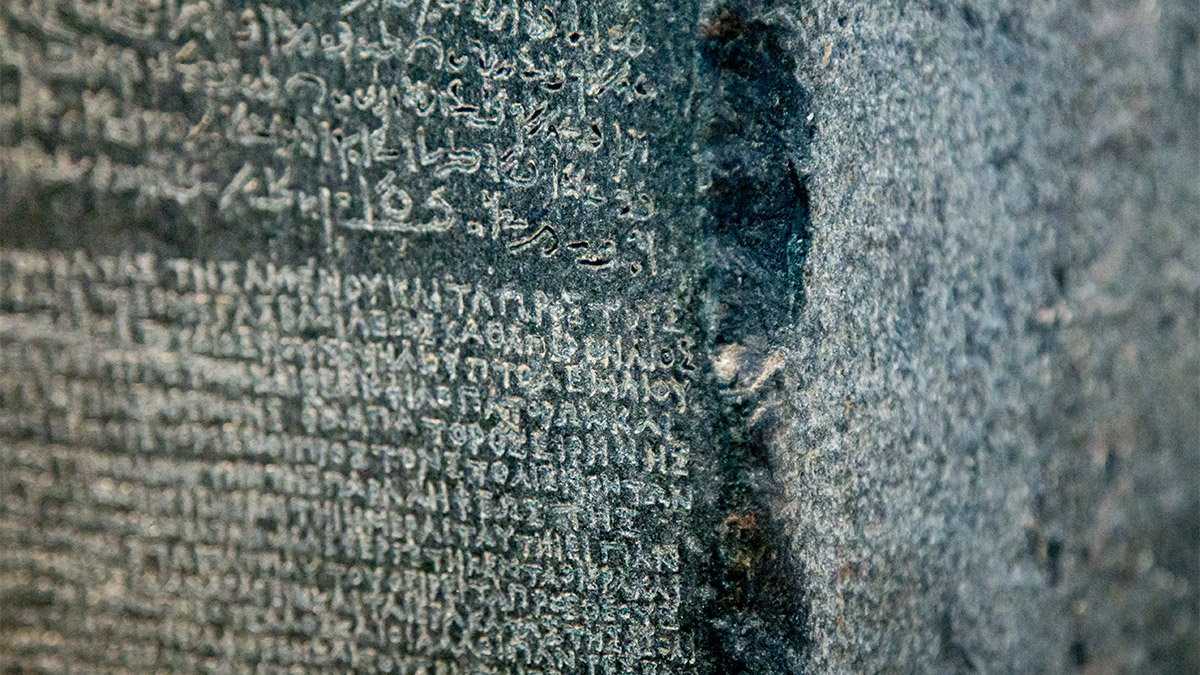

Battle site of 'Great Revolt' recorded on Rosetta Stone unearthed in Egypt

A battleground fought over by ancient Egyptians and the Ptolemaic Kingdom and mentioned on the Rosetta Stone has been discovered.

Archaeologists have long known about the Great Revolt, a battle between the ancient Egyptians and the Ptolemaic Kingdom that lasted from 207 B.C. to 184 B.C., because it is mentioned on the Rosetta Stone and in other historical texts. But now, archaeologists have finally discovered the exact location of one of the revolt's battles.

In 2009, archaeologists began excavating a site known as Tell el-Timai, where an ancient Greco-Roman industrial city called Thmouis was located on the Nile Delta of northern Egypt. The excavations were part of the Tell Timai Archaeological Project, an ongoing program by the University of Hawaii to learn more about Thmouis and the role it played in ancient Egypt. The team's findings were published Dec. 27, 2022 in the Journal of Field Archaeology.

The excavations revealed evidence that Thmouis was "ground zero" of a violent conflict, but at first the researchers weren't certain which one.

Over the next decade, they unearthed the remains of numerous buildings that had been burned to the ground, as well as a cache of artifacts that included weapons like ballista stones along with coins and a headless statue depicting the Ptolemaic queen Arsinoë II. They also discovered an abundance of unburied ancient human remains strewn about the city, according to the study.

"At first I was seeing things that piqued my curiosity and began to realize that we were looking at the destruction layer," study first author Jay Silverstein, project co-director of Tell Timai and an archaeologist and senior lecturer at Nottingham Trent University in the United Kingdom, told Live Science. "And then we started finding bodies."

Related: Why does the Rosetta Stone have 3 kinds of writing?

The Ptolemaic period (304 B.C. to 30 B.C.) was started by Ptolemy I Soter, one of Alexander the Great’s Macedonian generals. The Rosetta Stone contains a decree written in 196 B.C., during the reign of pharaoh Ptolemy V, when the Great Revolt was ongoing.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Both before and after the Ptolemies gained control, ancient Egyptians were meticulous when it came to burying the dead, even creating "elaborate underground embalming workshops," like the one recently discovered in Saqqara.

"In Egypt, people pay a lot of attention to burying people, so to have people unburied tells you a lot," Silverstein said. "All these findings were sending a message that there was some event here in history and we had to figure out what it was."

However, the identities of the deceased are unclear. "The unburied dead could be Greeks who lived at Thmouis who were overtaken by the violence of the insurrection, or they could be Egyptians who died defending the town," the researchers wrote in the study.

Dating the battleground

Using some of the artifacts plucked from the site, including coins pulled from beneath a home's floorboards, along with the discovery of an abandoned kiln complex where pottery was produced, archaeologists could better pinpoint the time period of the battle based on when the coins were minted.

During the excavation, they pulled fragments of imported Greek wares and shards of pottery, whose styles helped them determine that the ceramics probably dated to the Ptolemaic Kingdom, Silverstein said.

Within the kiln complex, archaeologists were surprised to find the remains of a man inside a kiln with his legs sticking out.

"I think it's possible that he had crawled into a non-functioning kiln to try to hide [during the attack]," Silverstein said.

Historical texts also confirm that the kilns were shut down near the end of the Early Ptolemaic period, when the Egyptians unsuccessfully tried to liberate themselves from Ptolemaic rule during the Great Revolt. The kilns that remained and were unearthed during the excavation were all "truncated at a uniform level," offering more evidence that an attack happened at the site, according to the study.

"The evidence of conflict and destruction at northern Thmouis is unequivocal, and the timing is well-placed … and thus coincides with the Great Revolt," the study authors wrote in their paper.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.