'Runaway' black hole the size of 20 million suns caught speeding through space with a trail of newborn stars behind it

Astronomers have discovered a "runaway" black hole, potentially the first observational evidence that supermassive black holes can be ejected from their host galaxies.

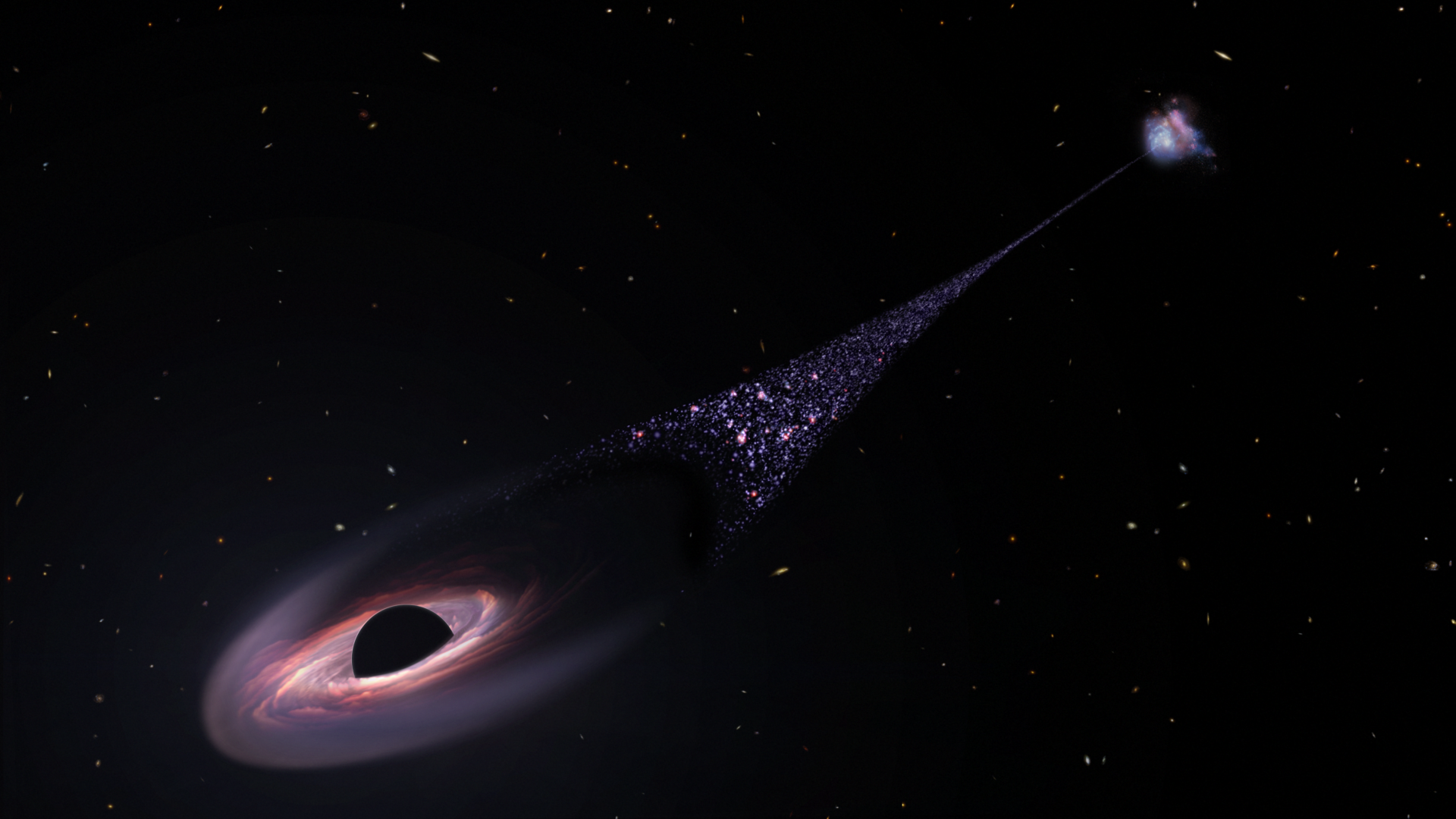

Astronomers have spotted a runaway supermassive black hole, seemingly ejected from its home galaxy and racing through space with a chain of stars trailing in its wake.

According to the team's research, which was published April 6 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the discovery offers the first observational evidence that supermassive black holes can be ejected from their home galaxies to roam interstellar space.

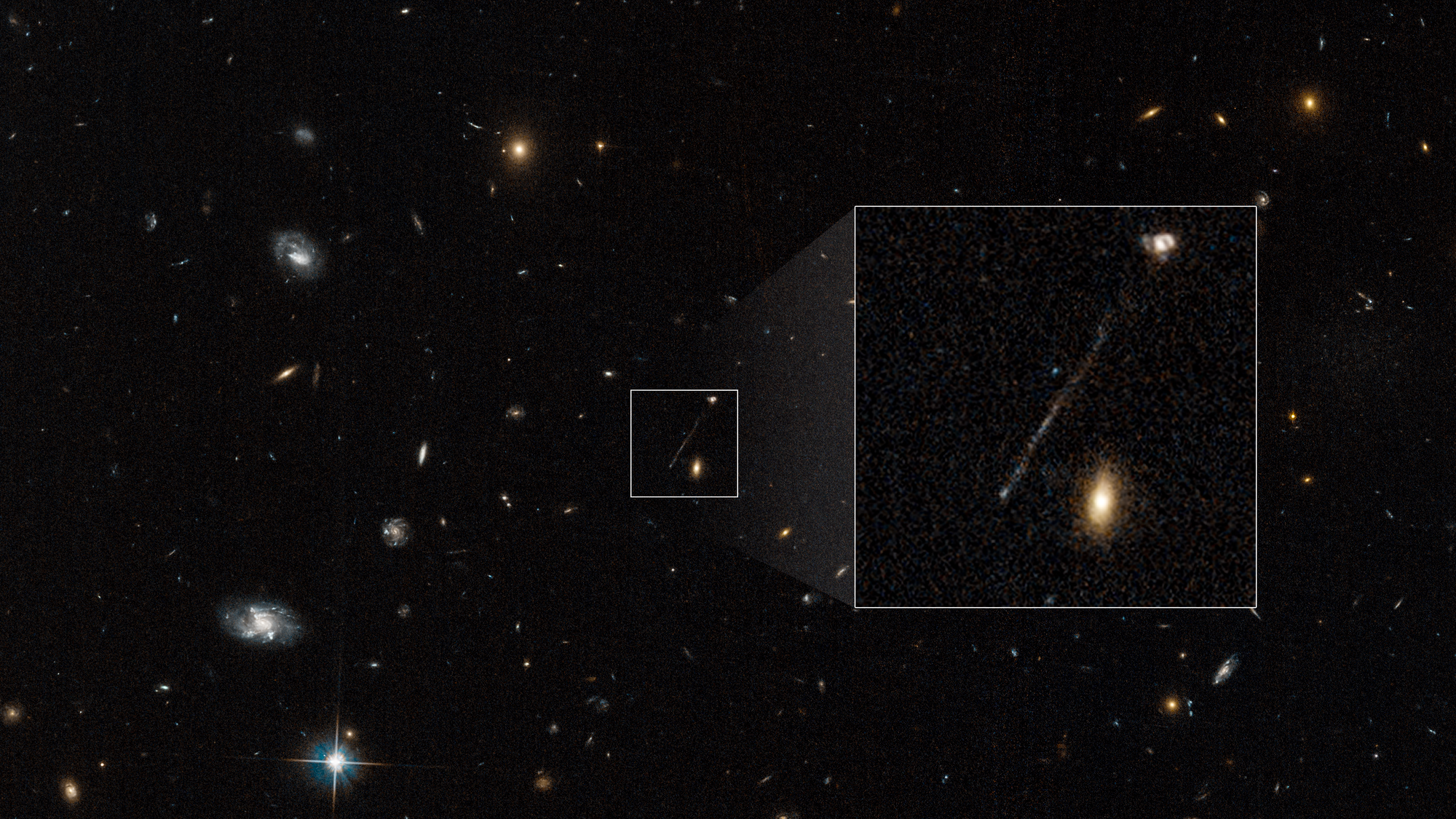

The researchers discovered the runaway black hole as a bright streak of light while they were using the Hubble Space Telescope to observe the dwarf galaxy RCP 28, located about 7.5 billion light-years from Earth.

Follow-up observations showed that the streak measures more than 200,000 light-years long — roughly twice the width of the Milky Way — and is thought to be made of compressed gas that is actively forming stars. The gas trails a black hole that is estimated to measure 20 million times the mass of the sun and is speeding away from its home galaxy at 3.5 million mph (5.6 million km/h), or roughly 4,500 times the speed of sound. This is fast enough to travel from Earth to the moon in about 14 minutes, according to a NASA statement.

According to the researchers, the streak points right to the center of a galaxy, where a supermassive black hole would normally sit.

"We found a thin line in a Hubble image that is pointing to the center of a galaxy," lead study author Pieter van Dokkum, a professor of physics and astronomy at Yale University, told Live Science. "Using the Keck telescope in Hawaii, we found that the line and the galaxy are connected. From a detailed analysis of the feature, we inferred that we are seeing a very massive black hole that was ejected from the galaxy, leaving a trail of gas and newly formed stars in its wake."

Confirming the tail of an ejected black hole

Most, if not all, large galaxies host supermassive black holes at their centers. Active supermassive black holes often launch jets of material at high speeds, which can be seen as streaks of light that superficially resemble the one the researchers spotted. These are called astrophysical jets.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To determine this isn't what they observed, van Dokkum and the team investigated this streak and found it didn't possess any of the telltale signs of an astrophysical jet. While astrophysical jets grow weaker as they move away from their source of emission, the potential supermassive black hole tail actually gets stronger as it progresses away from what seems to be its galactic point of origin, according to the researchers. Also, astrophysical jets launched by black holes fan out from their source, whereas this trail seems to have remained linear.

The team concluded that the explanation that best fits the streak is a supermassive black hole blasting through the gas that surrounds its galaxy while compressing that gas enough to trigger star formation in its wake.

"If confirmed, it would be the first time that we have clear evidence that supermassive black holes can escape from galaxies," van Dokkum said.

Black holes on the move

Once the runaway supermassive black hole is confirmed, the next question that astronomers need to answer is how such a monstrous object gets ejected from its host galaxy.

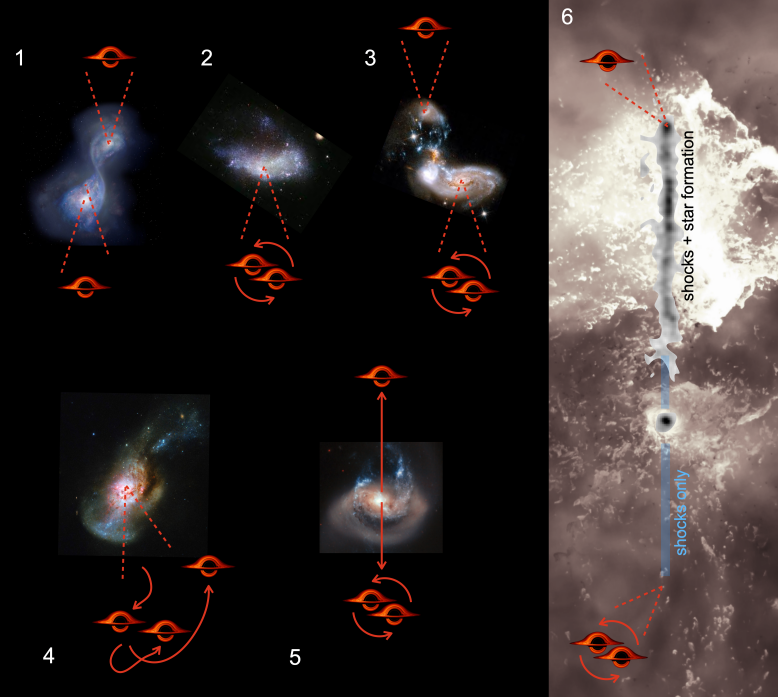

"The most likely scenario that explains everything we've seen is a slingshot, caused by a three-body interaction," van Dokkum said. "When three similar-mass bodies gravitationally interact, the interaction does not lead to a stable configuration but usually to the formation of a binary and the ejection of the third body."

This might mean that the runaway black hole was once part of a rare supermassive black hole binary, and during a galactic merger, a third supermassive black hole was introduced to this partnership, flinging out one of its occupants.

Astronomers aren't sure how common these massive runaways are.

"Ejected supermassive black holes had been predicted for 50 years but none have been unambiguously seen," van Dokkum said "Most theorists think that there should be many out there."

Further observations with other telescopes are needed to find direct evidence of a black hole at the mysterious streak's tip, van Dokkum added.

Editor's note: This article was updated on April 10 to reflect that the study has now been published in the peer-reviewed Astrophysical Journal Letters. Several new images were also added, coutesy of a NASA news release.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. who specializes in science, space, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, quantum mechanics and technology. Rob's articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University