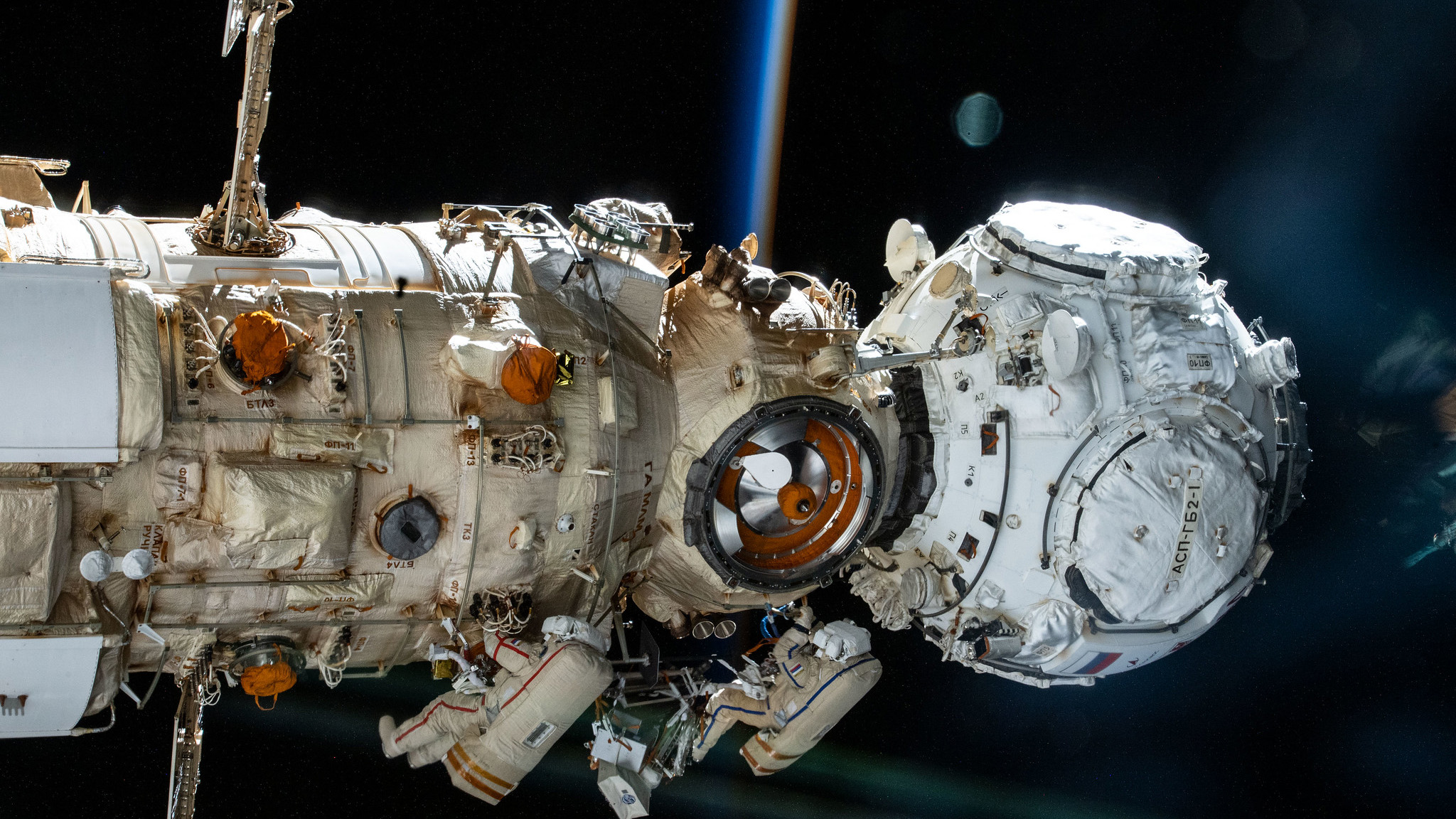

Russia could end its role in the International Space Station by 2024, say experts

The director general of Russia's Roscosmos space agency has threatened to end its Russia's involvement with the ISS.

Russia could end its cooperation on the International Space Station in as little as two years, using the sanctions imposed on Russia over its invasion of Ukraine as an excuse, according to space experts.

Most commentators characterize the threats by the director general of Russia's Roscosmos space agency to end its involvement with the orbital outpost as mere political bluster. But the threat to sever such relations could come to fruition, as some experts Live Science spoke to noted that Russia has only committed to the ISS project until 2024, rather than "after 2030" as had been proposed by NASA and other partners.

And Russia's withdrawal from the project could mean it will be mainly up to NASA to keep the ISS physically in orbit for almost another 10 years — something that Russia has been responsible for up until now. Even further, the threats signal just how badly Russia's actions in Ukraine have damaged ties in the scientific community between the country and the rest of the world, meaning that any science-related cooperation with Russia may be difficult, experts said.

Roscosmos chief Dmitry Rogozin stated in Russian on Twitter on Saturday (April 2) that "normal relations" between partners on the ISS could only be restored after "the complete and unconditional lifting of illegal sanctions."

Rogozin is a political figure with close ties to Russian president Vladimir Putin and a history of making blustery statements.

Related: Russia's Ukraine invasion could imperil international science

He tweeted on Feb. 24 — the day Russia invaded Ukraine — that any sanctions imposed as a result could "destroy" the partnership between Russia and the United States that keeps the ISS operating and aloft.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But activities on the space station have been relatively normal since then, with the arrival of three Russian cosmonauts in mid-March and the return to Earth of NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei last week on board a Russian Soyuz spacecraft.

Renewed threats

There may be more than political posturing, however, to Rogozin's latest threats to end Russia's cooperation on the ISS. In his tweets on Saturday, he shared what he said was a March 30 letter from NASA administrator Bill Nelson.

That letter stated the new sanctions were designed to allow continued cooperation between the U.S. and Russia, "to ensure continued safe operations of the ISS."

A statement by Nelson dated Sunday (April 3) and given to Live Science by a NASA spokesperson made the same point, and stressed that the "professional relationship" between astronauts and cosmonauts on the ISS was continuing to keep everyone safe on board.

But Rogozin claimed on Twitter he doesn’t agree that the ISS project can continue to operate under the international sanctions imposed on Russia.

"The purpose of the sanctions are to kill the Russian economy, plunge our people into despair and hunger and bring our country to its knees," he tweeted.

Meanwhile, the Moscow-based space analyst Andrey Ionin noted last week in an article in the Russian newspaper Izvestia that Russia could end its involvement on the ISS project as soon as 2024.

The first sections of the now-aging space station were boosted into orbit in 1998 and expected to last just 15 years; the ISS mission has since been extended, and NASA now proposes to keep it in orbit until at least 2030.

But "with the current sanctions, Roscosmos does not have a single argument for agreeing to the NASA proposal," Ionin said, and so the existing agreement to cooperate on the ISS could end in 2024.

Staying aloft

If Russia does end its involvement in the International Space Station, the greatest loss will be the rocket power that keeps it in orbit, which until now has been provided by regular bursts of the engines on the Soyuz spacecraft that dock there.

But U.S.-based space journalist Keith Cowing, the editor of NASA Watch, told Live Science that NASA will soon test the ability to keep the ISS in orbit using the engines of the Cygnus cargo spacecraft, which is manufactured and launched by the U.S. aerospace company Northrop Grumman: "So that isn’t as much of a threat as it once was," he said.

As a result, Cowing thinks NASA and its other partners will be able to keep the ISS in orbit for almost another decade even if Russia pulls out of the project. And since the start of flights by the Cygnus and Dragon spacecraft, NASA and the other partners on the ISS project — the European, Japanese and Canadian space agencies — are no longer reliant on Russia's Soyuz to carry crew and cargo to the space station, he said.

He warned that even if Russia chooses to continue its involvement, it could face international pressure on its activities in space because of its actions in Ukraine.

"The problem here is that they’ve gone beyond the pale, and I am not sure anybody will really want to work with them ever again," Cowing said.

Astrophysicist Martin Barstow of Leeds University in the United Kingdom chairs a group that oversees British science experiments on the ISS.

"I find it very sad that it has come to this," Barstow told Live Science. "Even during the depths of the Cold War, scientific cooperation has been able to continue, allowing a soft-power backchannel that has enabled scientists to meet to share ideas."

Barstow, too, is horrified by the events of the war. "The actions of Russia in invading Ukraine are so extreme that no scientist I know feels that we can continue the usual collaborations," he said.

The recent decision by the European Space Agency to suspend its collaboration with Russia on the ExoMars mission would, at a minimum, cause severe delays to the launch of a project that is very important to scientists in the region.

“However, we cannot compare this disappointment to the pain endured by the people of Ukraine," he said. "Russia withdrawing cooperation on the ISS is not a surprise, but it is a symptom of a country that has completely lost its moral compass."

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.