Ancient Slab Preserved Tracks of a Dinosaur, a 'Sailing Stone' and a Hopping Mammal

SAN FRANCISCO — Rocks that seem to propel themselves across desert landscapes have long mystified and intrigued scientists. Now, researchers have identified tracks of these so-called sailing stones dating back about 200 million years, in a rocky slab long prized for the five early dinosaur footprints it preserved.

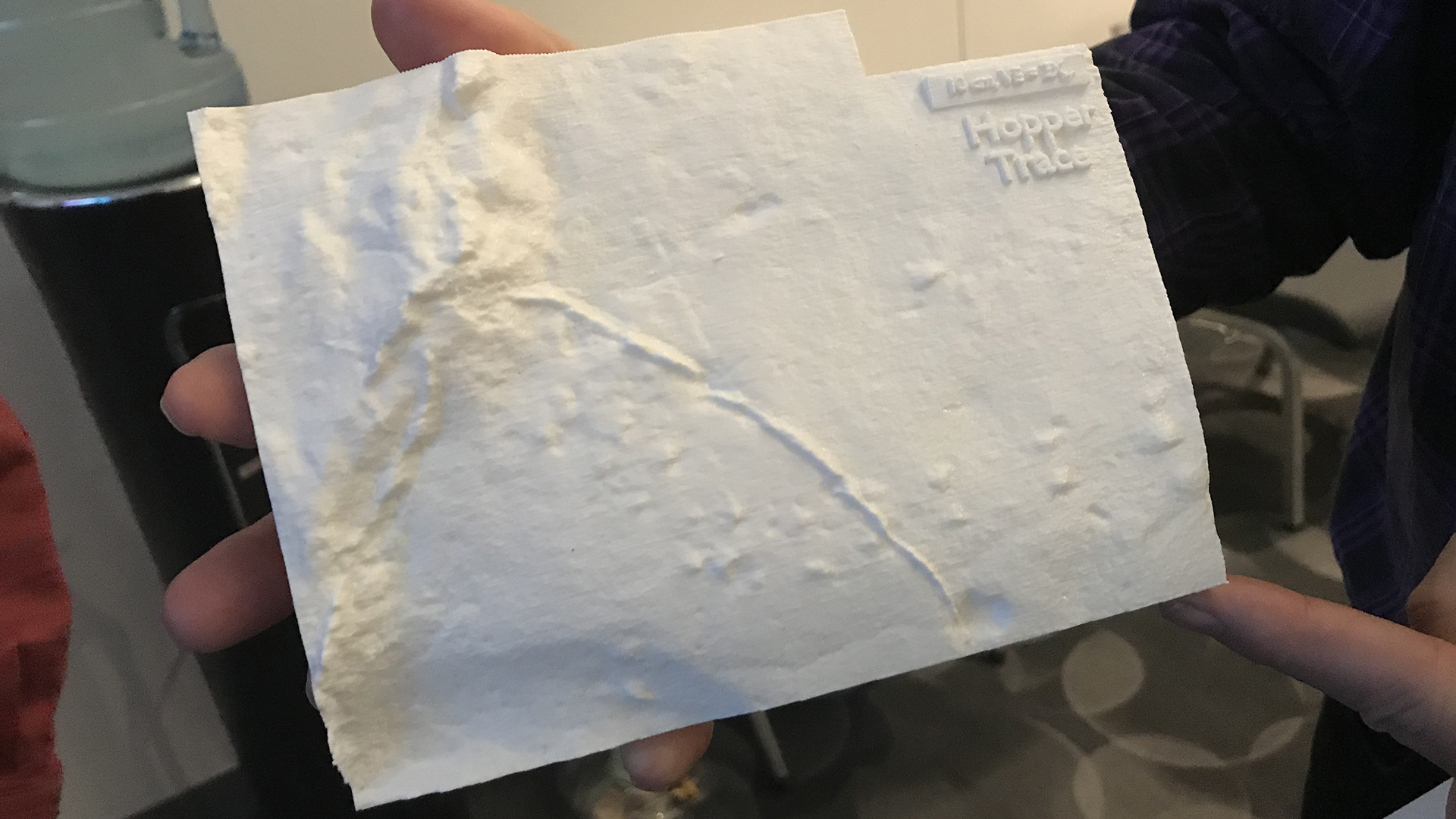

The 11-foot-long (3 meters) sandstone slab of dino prints was discovered more than a century ago, though some of the marks alongside those prints had gone unexamined. Some of the marks — a series of grooves — suggested that a stone once "sailed" across the surface of this rock, likely buoyed by a slick coating of ice and microbial slime, according to Paul Olsen, a paleontologist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in New York City.

Other clues in the stone hinted that the dinosaur and the sailing stone weren't the only ones to leave their marks; pairs of small depressions suggested that a tiny, hopping mammal also scampered across the surface, Olsen said Dec. 9 here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

Related: See Photos of Giant Sauropod Tracks in Scotland

The dinosaur tracks on the slab belonged to Anchisaurus, a prosauropod dinosaur (an early ancestor of enormous sauropods that emerged in the late Jurassic period. Scientists don't know what type of mammal produced the hopping tracks, but it may have been bounding into a burrow, Olsen said.

Sailing stones are known from the Racetrack Playa in California's Death Valley, where a number of stones have scraped long tracks behind them, as though they had been dragged across the dry lake bed. The long-standing mystery of how the sailing stones moved was solved in 2014, when scientists reported that coatings of water on the rocks formed thin sheets of ice that enabled winds to propel the stones over the lake bed, creating grooved tracks.

The ancient stone slab was excavated from a quarry in Portland, Connecticut, and around 200 million years ago, that region of the world was humid and tropical. However, it could have endured a temporary cooling period following explosive volcanic eruptions that spewed masses of sulfur into the atmosphere, Olsen explained. If the grooves on the rock were created by an ice-coated sailing stone, that's a strong piece of evidence for that ancient tropical freeze, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, there's something else that could have made a rock slick enough to sail: microbial mats. Slimy coatings of microbial goo have created sailing stones in Spain, and similar microbial coatings could also have covered the stone that sailed 100 million years ago, Olsen said.

While the slab was on display in Connecticut since 1896, first at Wesleyan University and then at Dinosaur State Park, these newly identified mammal tracks and grooves "hid in plain sight for over 123 years," Olsen said at the AGU meeting.

- Photos: The World's Weirdest Geological Formations

- Images: Magnificent Geological Formations of the American West

- Photos: Dinosaur Tracks Reveal Australia's 'Jurassic Park'

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.