Hidden, never-before-seen penguin colony spotted from space

Satellite photos showing poop stains in the West Antarctic snow and ice have revealed a previously unknown breeding colony of emperor penguins.

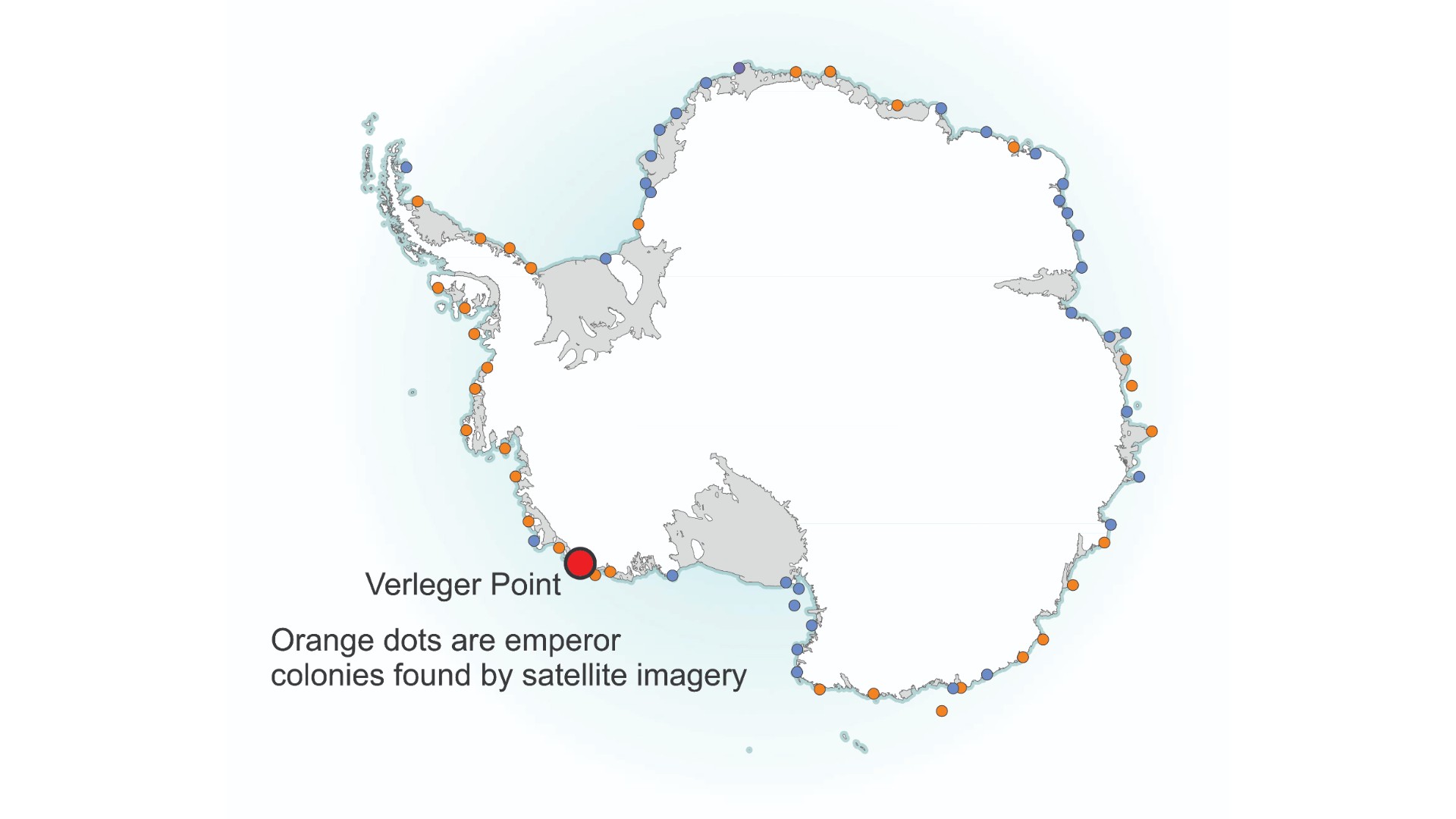

A never-before-seen emperor penguin colony — one of only 66 known to exist — has been spotted by accident in satellite photographs of West Antarctica that clearly show their guano, or droppings, staining the ice.

The colony is estimated to be home to about 1,000 adult birds, in 500 pairs with their young, which makes it relatively small for an emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) breeding site. But it's an important addition to what's known of the species.

Peter Fretwell, a geographic information officer with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), discovered the colony in December; but the announcement was delayed so that it coincided with Penguin Awareness Day, which is held on Jan. 20 each year.

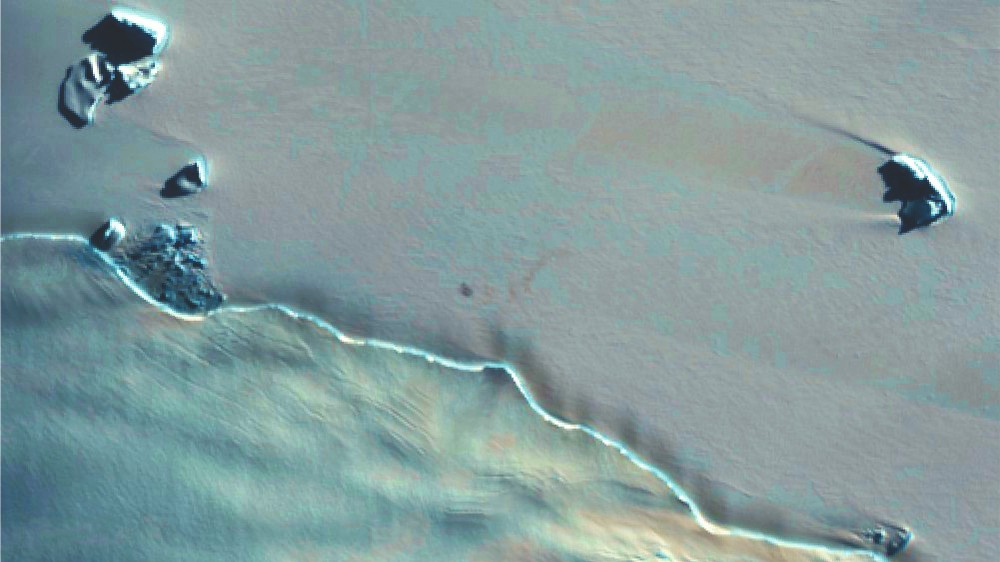

Fretwell told Live Science that he was looking at sea ice loss in photographs from the European Space Agency's two Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites when he spotted the distinctive signs of an emperor penguin colony. "I could see what looked like a very small brown stain on the ice," he said.

Related: Over 60 million years ago, penguins abandoned flight for swimming. Here’s how.

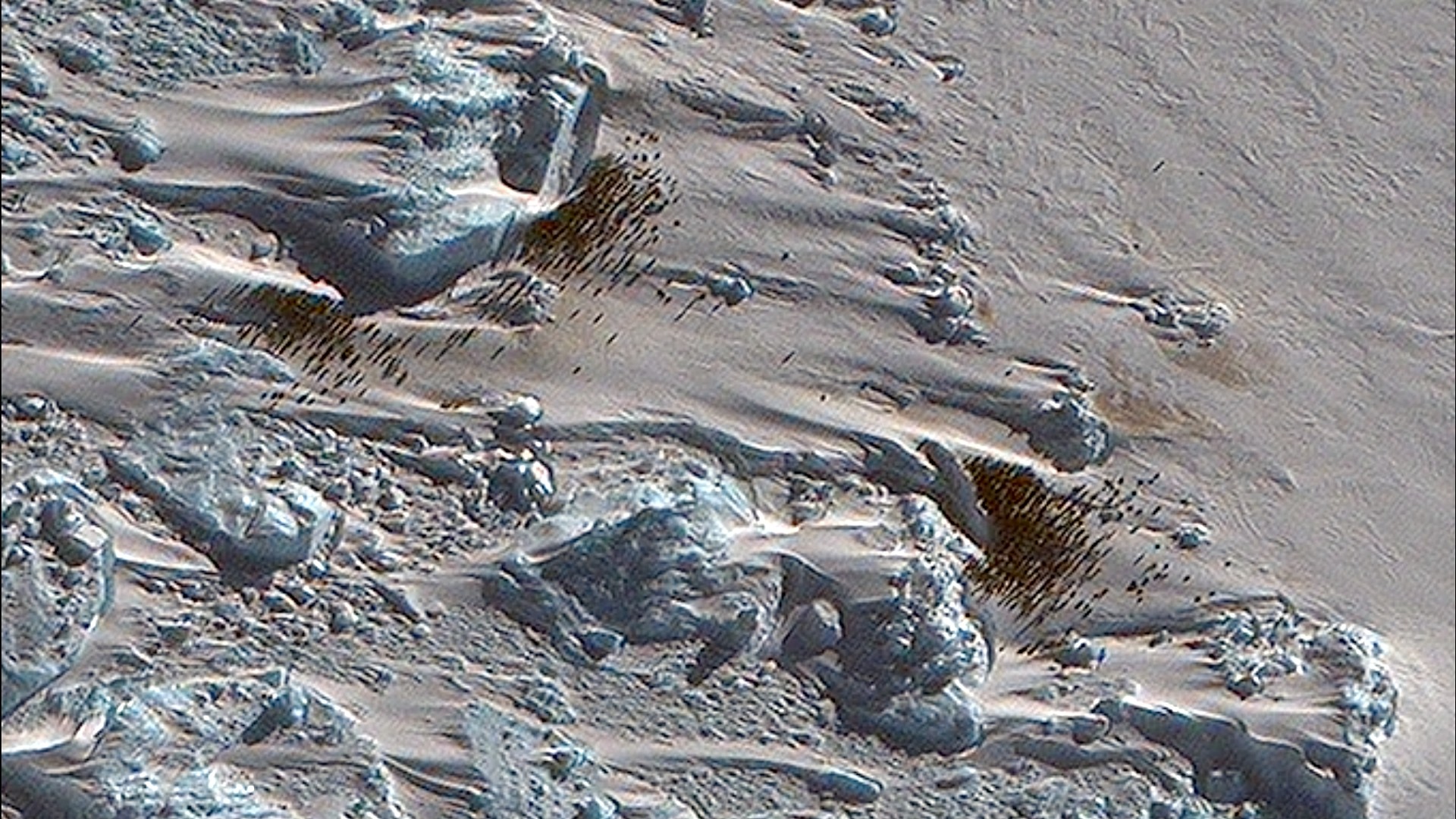

Higher resolution photographs of the same area taken in October by the Maxar WorldView-3 satellite, which can image objects as small as 12 inches (30 centimeters) across, confirmed the presence of the breeding colony, near West Antarctica's Verleger Point, Fretwell said.

Because the penguins' guano accumulates and stains the ice and snow a deep-brown color, it is much easier to see from afar than the emperor penguins themselves. But the high-resolution images also show individual emperor penguins — pictured as tiny dots — and the population estimate is based on those, Fretwell said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Seabirds by satellite

Emperor penguin colonies are often remote and difficult to study, but BAS scientists have discovered several in satellite photos of Antarctica's coastline over the past 15 years. Recent satellite research has even suggested that there could be around 20% more emperor penguins in the Antarctic than previously estimated.

Emperor penguins exclusively breed on packed sea ice. This reliance on sea ice, however, also makes the penguins vulnerable to its loss in a warming climate; and West Antarctica has already been badly affected.

"Last year we had the minimum ever sea ice extent in Antarctica, and this year is even worse, for two consecutive years," Fretwell said. "It's estimated that we will probably lose a minimum of 80% of emperor penguin colonies before the end of the century."

Due to this threat from climate change, emperors are now listed as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Stately penguins

Emperor penguins are the tallest and heaviest of all penguins, typically reaching up to 39 inches (100 cm) in height and weighing up to 100 pounds (45 kilograms.) They get their name from their dramatic black, white and yellow plumage.

Emperors spend most of the Antarctic summer diving for fish, crustaceans and krill. They breed during the dark winter months on the surface of the packed sea ice, sometimes more than 30 miles (50 kilometers) from the open ocean, and where temperatures can dip as low as minus 76 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 60 Celsius.).

Fretwell recently visited Antarctica to observe another large emperor penguin colony by aerial drone, to confirm the numerical estimates of penguin breeding colonies only seen in satellite photographs.

And while he got close enough to smell the penguin poop, it wasn't that bad, he said.

Because emperor penguin colonies are on sea ice, much of the guano is frozen and doesn't smell — unlike the colonies of penguins that breed among rocks, where the smell can be intense. "The emperors are more stately and not as smelly as other penguins," he said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.